Koreans in Japan

This article mayrequirecleanupto meet Wikipedia'squality standards.The specific problem is:Scope of article and lead are misleading. Multiple groups of Koreans exist in Japan, one of which arrived after 1945. The title of the article implies encompassing all groups, not just the 1945 and before arrivals.(July 2024) |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 434,461 (December 2023) (in December, 2023)[1] (December 2023)[2] Details[2]

| |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Tokyo(Shin-Ōkubo)·Osaka Prefecture(Ikuno-ku) | |

| Languages | |

| Japanese·Korean(Zainichi Korean) | |

| Religion | |

| Buddhism·Shinto/Korean Shamanism·Christianity·Irreligion | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Korean people·Sakhalin Koreans |

| Koreans in Japan | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North Korean name | |||||||

| Chosŏn'gŭl | 재일 조선인 | ||||||

| Hancha | Ở ngày Triều Tiên người | ||||||

| |||||||

| South Korean name | |||||||

| Hangul | 재일 한국인 | ||||||

| Hanja | Ở ngày Hàn Quốc người | ||||||

| |||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||

| Kanji | Ở ngày Hàn Quốc ・ Triều Tiên người | ||||||

| Kana | ざいにちかんこく・ちょうせんじん | ||||||

| |||||||

| Part ofa serieson |

| Koreans in Japan |

|---|

Koreans in Japan(Ở ngày Hàn Quốc người ・ ở Nhật Bản Triều Tiên người ・ Triều Tiên người,Zainichi Kankokujin/Zainihon Chōsenjin/Chōsenjin)(Korean:재일 한국/조선인) are ethnicKoreanswho immigrated to Japan before 1945 and are citizens or permanent residents ofJapan,or who are descendants of those immigrants. They are a group distinct from South Korean nationals who have immigrated to Japan since the end ofWorld War IIand thedivision of Korea.

They currently constitute the second largest ethnic minority group in Japan afterChinese immigrants,due to many Koreans assimilating into the general Japanese population.[3]The majority of Koreans in Japan areZainichi Koreans(Ở ngày Hàn Quốc ・ Triều Tiên người,Zainichi Kankoku/Chōsenjin),often known simply asZainichi(Ở ngày,lit. 'in Japan'),who are ethnic Korean permanent residents of Japan. The term Zainichi Korean refers only to long-term Korean residents of Japan who trace their roots toKorea under Japanese rule,distinguishing them from the later wave of Korean migrants who came mostly in the 1980s,[4]and from pre-modern immigrants dating back to antiquity who may themselves be the ancestors of the Japanese people.[5]

The Japanese word "Zainichi" itself means a foreign citizen "staying in Japan", and implies temporary residence.[6]Nevertheless, the term "Zainichi Korean" is used to describe settled permanent residents of Japan, both those who have retained theirJoseonorNorth Korean/South Koreannationalities, and even sometimes includes Japanese citizens of Korean descent who acquired Japanesenationalityby naturalization or by birth from one or both parents who have Japanese citizenship.

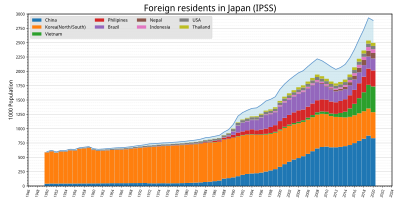

Statistics

[edit]

According to theMinistry of Justice,410,156 South Koreans and 24,305 Koreans(Triều Tiên người,Chōsen-jin)(those "Koreans" do not necessarily have the North Korean nationality) are registered in 2023.[7][8]

History

[edit]Overview

[edit]The modern flow of Koreans to Japan started with theJapan-Korea Treaty of 1876and increased dramatically after 1920. During World War II, a large number of Koreans were also conscripted by Japan. Another wave of migration started after South Korea was devastated by the Korean War in the 1950s. Also noteworthy was the large number of refugees from themassacres on Jeju Islandby the South Korean government.[9]

Statistics regarding Zainichi immigration are scarce. However, in 1988, aMindanyouth group called Zainihon Daikan Minkoku Seinendan (Korean:재일본대한민국청년회,Japanese:Ở Nhật Bản đại Hàn dân quốc thanh niên sẽ) published a report titled, "Father, tell us about that day. Report to reclaim our history" (Japanese:アボジ nghe かせて あ の ngày の ことを— ta 々 の lịch sử を lấy り lệ す vận động báo cáo thư). The report included a survey of first generation Koreans' reasons for immigration. The result was 13.3% for conscription, 39.6% for economics, 17.3% for marriage and family, 9.5% for study/academic, 20.2% for other reasons and 0.2% unknown.[10]The survey excluded those who were under 12 when they arrived in Japan.

Pre-modern era

[edit]While some families can currently trace their ancestry back to pre-modern Korean immigrants, many families were absorbed into Japanese society and as a result, they are not considered a distinct group. The same is applicable to those families which are descended from Koreans who entered Japan in subsequent periods of pre-modernJapanese history.Trade with Korea continued to modern times, with Japan also periodically receiving missions from Korea, though this activity was often limited to specific ports.

Yayoi period

[edit]In late prehistory, in theIron AgeYayoi period(300 BCE to 300 CE), Japanese cultureshowed[clarify]some Korean influence, though whether this was accompanied by immigration from Korea is debated (seeOrigin of the Yayoi people).

Kofun period (250 to 538)

[edit]In the laterKofun(250–538 CE) andAsuka(538–710 CE) periods, there was some flow of people from the Korean Peninsula, both as immigrants and long-term visitors, notably a number of clans in the Kofun period (seeKofun period Korean migration). While some families today can ultimately trace their ancestry to the immigrants, they were generally absorbed into Japanese society and are not considered a distinct modern group.[by whom?][citation needed]

Heian period (794 to 1185)

[edit]According to theNihon Kōkihistorical text, in 814, six people, including aSillaman called Karanunofurui (Korean:가라포고이,Japanese: Thêm bày ra cổ y; presumed to be ofgayadescent) became naturalized in Japan'sMinokuni( mỹ nùng quốc ) region.[11]

Sengoku period (1467 to 1615)

[edit]Some Koreans entered Japan in captivity as a result of pirate raids or during the 1592–1598Japanese invasions of Korea.

Edo period (1603 to 1867)

[edit]In theEdo period,trade with Korea occurred through theTsushima-Fuchū DomaininKyūshū,nearNagasaki.

Before World War II

[edit]After the conclusion of theJapan-Korea Treaty of 1876,Korean students and asylum seekers started to come to Japan, including Korean politicians and activistsBak Yeonghyo,Kim Ok-gyun,andSong Byeong-jun.There were about 800 Koreans living in Japan before Japan annexed Korea.[12]In 1910, as the result of theJapan–Korea Annexation Treaty,Japan annexed Korea, and all Korean people became part of the nation of theEmpire of Japanby law and received Japanese citizenship.

In the 1920s, the demand for labor in Japan was high while Koreans had difficulty finding jobs in theKorean peninsula.As a result, thousands of Koreans migrated or were recruited to work in industries like coal mining.[13]A majority of the immigrants consisted of farmers from the southern part of Korea.[14]The number of Koreans in Japan in 1930 was more than ten times greater than that of 1920, reaching 419,000.[15]However, the jobs they could get on the mainland of Japan were curtailed by open discrimination and largely limited to physical labor due to their poor education; they usually worked alongside other groups of ethnic minorities subject to discrimination, such asburakumin.[14]

BeforeWorld War II,the Japanese government tried to reduce the number of Koreans immigrating to Japan. To accomplish this, the Japanese government devoted resources to theKorean peninsula.[16][verification needed]

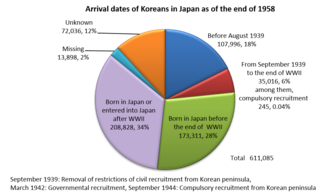

During World War II

[edit]In 1939, the Japanese government introduced theNational Mobilization Lawand conscripted Koreans to deal with labor shortages due toWorld War II.In 1944, the Japanese authorities extended the mobilization of Japanese civilians for labor on the Korean peninsula.[17]Of the 5,400,000 Koreans conscripted, about 670,000 were taken to mainland Japan (includingKarafuto Prefecture,present-daySakhalin,now part ofRussia) for civilian labor. Those who were brought to Japan were forced to work in factories, in mines, and as laborers, often under appalling conditions. About 60,000 are estimated to have died between 1939 and 1945.[18]Most of the wartime laborers returned home after the war, but some elected to remain in Japan. 43,000 of those in Karafuto, which had been occupied by theSoviet Unionjust before Japan's surrender, were refused repatriation to either mainland Japan or the Korean Peninsula, and were thus trapped in Sakhalin, stateless; they became the ancestors of theSakhalin Koreans.[19]

After World War II

[edit]Koreans entered Japan illegally post-World War II due to an unstable political and economic situation in Korea, with 20,000 to 40,000 Koreans fleeingSyngman Rhee's forces during theJeju uprisingin 1948.[20]TheYeosu-Suncheon rebellionalso increased the illegal immigration to Japan.[21]It is estimated that between 1946 and 1949, 90% of illegal immigrants to Japan were Koreans.[22][verification needed]During theKorean War,Korean immigrants came to Japan to avoid torture or murder at the hands of dictatorSyngman Rhee's forces (e.g., in theBodo League massacre).[23]

Fishers and brokers helped immigrants enter Japan throughTsushima Island.[24][25]In the 1950s,Japan Coast Guardsecured the border with Korea, but apprehending illegal immigrants was difficult because they were armed, whileJapan Coast Guardwas not due to the terms of thesurrender of Japanafter World War II. During this period, one-fifth of the immigrants were arrested.[26]

In Official Correspondence of 1949,Shigeru Yoshida,the prime minister of Japan, proposed the deportation of all Zainichi Koreans toDouglas MacArthur,the AmericanSupreme Commander of the Allied Powers,and said the Japanese government would pay all of the cost. Yoshida stated that it was unfair for Japan to purchase food for illegal Zainichi Koreans, claiming that they did not contribute to the Japanese economy and that they supposedly committed political crimes by cooperating with communists.[27]

Loss of Japanese nationality

[edit]

Immediately following the end of World War II, there were roughly 2.4 million Koreans in Japan; the majority repatriated to their ancestral homes in the southern half of the Korean Peninsula, leaving only 650,000 in Japan by 1946.[28]

Japan's defeat in the war and the end of its colonization of the Korean Peninsula andTaiwanleft the nationality status of Koreans and Taiwanese in an ambiguous position in terms of law. TheAlien Registration Ordinance(Người nước ngoài đăng lục lệnh,Gaikokujin-tōroku-rei)of 2 May 1947 ruled that Koreans and some Taiwanese were to be provisionally treated as foreign nationals. Given the lack of a single, unified government on the Korean Peninsula, Koreans were provisionally registered under the name ofJoseon(Korean:조선,Japanese:Chōsen,Triều Tiên), the old name of undivided Korea.

In 1948, the northern and southern parts of Korea declared independence individually, makingJoseon,or the old undivided Korea, a defunct nation. The new government of theRepublic of Korea(South Korea) made a request to the Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers, then theoccupying power of Japan,to change the nationality registration of Zainichi Koreans toDaehan Minguk(Korean:대한민국;Japanese:Daikan Minkoku,Đại Hàn dân quốc), the official name of the new nation. Following this, from 1950 onwards, Zainichi Koreans were allowed to voluntarily re-register their nationality as such.

The Allied occupation of Japan ended on 28 April 1952 with theSan Francisco Peace Treaty,in which Japan formally abandoned its territorial claim to the Korean Peninsula, and as a result, Zainichi Koreans formally lost their Japanese nationality.[29]

The division on the Korean Peninsula led to division among Koreans in Japan.Mindan,the Korean Residents Union in Japan, was set up in 1946 as a pro-South offshoot ofChōren(League of Koreans in Japan), the main Korean residents' organisation, which had a socialist ideology. Following theMay Day riots of 1952,the pro-North organisation[which?]was made illegal, but it re-formed under various guises and went on to form the "General Association of Korean Residents in Japan", orChongryon,in 1955. This organisation kept to its socialist, and by extension pro-North stance, and enjoyed the active financial support of the North Korean government.[28]

In 1965, Japan concluded aTreaty on Basic Relations with the Republic of Koreaand recognized the South Korean government as the only legitimate government of the peninsula.[28]Those Koreans in Japan who did not apply for South Korean citizenship keptChōsen-sekiwhich did not give them citizenship of any nation.

Newcomers

[edit]Starting in 1980, South Korea allowed its students to study abroad freely; starting in 1987, people older than forty-four were allowed to travel abroad.[30][31]One year after the1988 Seoul Olympics,traveling abroad was further liberalized.[31]WhenExpo 2005was held, the Japanese government had a visa waiver program with South Korea for a limited period under the condition that the visitor's purpose was sightseeing or business, and later extended it permanently.[32]Korean enclaves tend to exclude newcomers from existing Korean organizations, especiallyMindan,so newcomers have created a new one called theFederation of Korean Associations in Japan.[33][34]

In recent years, there has been a noticeable shift in the perception of Zainichi Koreans in Japan, largely influenced by the growing popularity of Korean culture, known as the "Korean Wave"or Hallyu. This cultural phenomenon, encompassing Korean music, television dramas, films, and cuisine, has gained widespread attention not only in Japan but also globally. As a result, there has been an increased appreciation for Korean culture among the Japanese population, leading to greater interest in Zainichi Koreans and their heritage.[35]

The Korean Wave has played a significant role in bridging cultural gaps and fostering greater acceptance of Zainichi Koreans in Japanese society.K-popmusic groups, such asEXO,TwiceandBLACKPINK,have garnered massive followings in Japan, garnering interest in Korean entertainment. Similarly, Korean dramas and films have found a dedicated audience in Japan, contributing to the normalization of Korean culture within mainstream Japanese media.[35]

Furthermore, economic opportunities have also contributed to a recent influx of Korean newcomers to Japan. Despite historical tensions between the two countries, Japan remains an attractive destination for many South Koreans seeking employment and business prospects. The close geographical proximity and strong economic ties between Japan and South Korea have facilitated increased migration and investment between the two nations.

Japan's aging population and labor shortages in certain industries have created demand for foreign workers, including Koreans. Many Korean nationals have sought employment opportunities in sectors such as manufacturing, technology, healthcare, and hospitality, contributing to Japan's workforce and economy.[36]

Repatriation to Korea

[edit]

Repatriation of Zainichi Koreans from Japan conducted under the auspices of theJapanese Red Crossbegan to receive official support from the Japanese government as early as 1956. A North Korean-sponsored repatriation programme with support of theChōsen Sōren(The General Association of Korean Residents in Japan) officially began in 1959. In April 1959,Gorō Terao(Chùa đuôi Ngũ LangTerao Gorō), a political activist and historian of theJapanese Communist Party,published the book,North of the 38th Parallel(Japanese:38 độ tuyến の bắc), in which he praised North Korea for its rapid development andhumanitarianism.[37]Following its publication, numbers of returnees skyrocketed. The Japanese government was in favour of repatriation as a way to rid the country of ethnic minority residents that were discriminated against and regarded as incompatible with Japanese culture.[38]Though the United States government was initially unaware of Tokyo's cooperation with the repatriation programme, they offered no objection after they were informed of it; the US ambassador to Japan was quoted by his Australian counterpart as describing the Koreans in Japan as, "a poor lot including many Communists and many criminals".[39]

Despite the fact that 97% of the Zainichi Koreans originated from the southern half of theKorean Peninsula,the North was initially a far more popular destination for repatriation than the South. Approximately 70,000 Zainichi repatriated to North Korea during a two-year period from 1960 through 1961.[40]However, as word came back of difficult conditions in the North and with the 1965 normalization ofJapan-South Korea relations,the popularity of repatriation to the North dropped sharply, though the trickle of returnees to the North continued as late as 1984.[41]In total, 93,340 people migrated from Japan to North Korea under the repatriation programme; an estimated 6,000 wereJapanese migrating with Korean spouses.Around one hundred such repatriates are believed to have laterescaped from North Korea;the most famous isKang Chol-Hwan[disputed–discuss],who published a book about his experience,The Aquariums of Pyongyang.One returnee who later defected back to Japan, known only by his Japanese pseudonym Kenki Aoyama, worked for North Korean intelligence as a spy inBeijing.[42]

The repatriations have been the subject of numerous creative works in Japan, due to the influence they had on the Zainichi Korean community. One documentary film about a family whose sons repatriated while the parents and daughter remained in Japan,Dear Pyongyang,won a special jury prize at the 2006Sundance Film Festival.[43][44]

Some Zainichi Koreans have gone to South Korea to study or to settle. For example, authorLee Yangjistudied atSeoul National Universityin the early 1980s.[45]

Organizations – Chongryon and Mindan

[edit]Division between Chongryon and Mindan

[edit]Well into at least the 1970s,Chongryonwas the dominant Zainichi group, and in some ways remains more politically significant today in Japan. However, the widening disparity between the political and economic conditions of the two Koreas has since madeMindan,the pro-South Korean group, the larger and less politically controversial faction. 65% of Zainichi are now said to be affiliated to Mindan. The number of pupils receiving ethnic education from Chongryon-affiliated schools has declined sharply, with many, if not most, Zainichi now opting to send their children to mainstream Japanese schools.[citation needed]Some Chongryon schools have been closed for lack of funding, and there is serious doubt as to the continuing viability of the system as a whole. Mindan has also traditionally operated a school system for the children of its members, although it has always been less widespread and organized compared to its Chongryon counterpart, and is said to be nearly defunct at the present time.[citation needed]

Chongryon

[edit]Out of the two Korean organizations in Japan, the pro-North Chongryon has been the more militant in terms of retaining Koreans' ethnic identity. Its policies have included:

- operation of about 60 ethnic Korean schools across Japan, initially partly funded by the North Korean government, in which lessons are conducted in Korean. They maintain a strong pro-North Korean ideology, which has sometimes come under criticism from pupils, parents, and the public alike;

- discouraging its members from taking up Japanese citizenship;

- discouraging its members from marrying Japanese;

- operation of businesses and banks to provide the necessary jobs, services, and social networks for Zainichi Koreans outside mainstream society;

- opposition to Zainichi Koreans' right to vote or participate in Japanese elections, which is seen as an unacceptable attempt at assimilation into Japanese society;[46]

- and a home-coming movement to North Korea in the late 1950s,[47]which it hailed as a socialist "Paradise on Earth", with some 90,000 Zainichi Koreans and their Japanese spouses moving to the North before the migration eventually died down.

Controversies over Chongryon

[edit]For a long time, Chongryon enjoyed unofficial immunity from searches and investigations, partly because authorities were reluctant to carry out any actions which could provoke not only accusations of xenophobia but lead to an international incident. Chongryon has long been suspected of a variety of criminal acts on behalf of North Korea, such as illegal transfer of funds to North Korea and espionage, but no action has been taken.[citation needed]However, recently escalating tensions between Japan and North Korea over a number of issues, namelyNorth Korea'sabduction of Japanese nationalswhich came to light in 2002 as well asits nuclear weapons program,has led to a resurgence of public animosity against Chongryon. Chongryon schools have alleged numerous cases of verbal abuse and physical violence directed against their students and buildings, and Chongryon facilities have been targets of protests and occasional incidents. The Japanese authorities have recently started to crack down on Chongryon, with investigations and arrests for charges ranging from tax evasion to espionage. These moves are usually criticized by Chongryon as acts of political suppression.[48]

In December 2001, police raided Chongryon's Tokyo headquarters and related facilities to investigate Chongryon officials' suspected role in embezzlement of funds from the failedTokyo Chogin credit union.[49]

In 2002, Shotaro Tochigi, deputy head of thePublic Security Investigation Agency,told a session of theHouse of RepresentativesFinancial Affairs Committee that the agency was investigating Chongryon for suspected illicit transfers of funds to the North.[50]The image of Chongryon was further tarnished by North Korea's surprise 2002 admission that it had indeed abducted Japanese nationals in the 1970s, even after it had categorically and fiercely denied for many years that the abductions had ever taken place and dismissed rumors of North Korean involvement as an allegedly "racist fantasy". Some of the recent drop in membership of Chongryon is attributed to ordinary members of Chongryon who may have believed in the party line feeling deeply humiliated and disillusioned upon discovering that they had been used as mouthpieces to deny the crimes of the North Korean government.[citation needed]

In March 2006, police raided six Chongryon-related facilities in an investigation into the circumstances surrounding the June 1980 disappearance of one of the alleged abductees, Tadaaki Hara. Police spokesmen said that the head of Chongryon at the time was suspected of co-operating in his kidnapping.[51]

The operation of theMangyongbong-92(currently suspended), a North Korean ferry that is the only regular direct link between North Korea and Japan, is a subject of significant tension, as the ferry is primarily used by Chongryon to send its members to North Korea and to supply North Korea with money and goods donated by the organization and its members. In 2003, a North Korean defector made a statement to the US Senate committee[which?]stating that more than 90% of the parts used by North Korea to construct its missiles were brought from Japan aboard the ship.[52]

In May 2006, Chongryon and the pro-South Mindan agreed to reconcile, only for the agreement to break down the following month.North Korea's missile testsin July 2006 deepened the divide, with Chongryon refusing to condemn the missile tests, expressing only its regret that the Japanese government has suspended the operation of theMangyongbong-92.Outraged senior Mindan officials joined mainstream Japanese politicians and media in sharply criticizing Chongryon's silence over the matter.

Integration into Japanese society

[edit]

During the post-World War II period, Zainichi Koreans faced various kinds of discrimination from Japanese society. Due to theSan Francisco Peace Treaty,the Japanese government created laws to support Japanese citizens by giving financial support, providing shelters, etc. However, after the treaty was signed, Zainichi Koreans were no longer counted as Japanese citizens, so they were unable to get any support from the government. They were unable to get an insurance certificate from the government, so it was difficult for them to get any medical care. Without medical insurance, Zainichi Koreans were unable to go to the hospital since the cost of medication was too high.[citation needed]

Another problem caused by this treaty was that the Japanese government created a law which stated that Korean residents in Japan had to be fingerprinted since Zainichi Koreans had two names (their original name and a name given by the Japanese government). Under this law, Zainichi Koreans had to reveal their identity to the public because when they visited the city hall to provide their fingerprints, their neighbors found out that they were Zainichi Koreans. Therefore, Zainichi Koreans were forced to reveal their identity to Japanese and faced discrimination from them. This made their lives even more difficult. In order to protect themselves, many Zainichi Koreans protested against this law.Mindanand many Zainichi Koreans opposed this law, but the law wasn't repealed until 1993. Until then, Zainichi Koreans could not escape from the social discrimination which they had faced in Japanese society.[53]

Discrimination

[edit]Furthermore, it was hard for the Zainichi Koreans to get a job due to discrimination. Zainichi Koreans were often forced into low-wage labor, lived in segregated communities, and faced barriers to their cultural and social practices. Especially, it was very hard for Zainichi Koreans to become public employees since Japan only let Japanese nationals become public employees at that time. Even of those who were able to secure jobs, many ended up working in coal mines, construction sites, and factories under harsh conditions that were markedly worse than those endured by their Japanese counterparts. The disparity was not limited to wages alone; Koreans also faced longer working hours and were subjected to physical abuse by supervisors who enforced strict discipline to maximize productivity.[54]Since many Zainichi Koreans could not get a proper job, they began to get involved in illegal jobs such as "illegal alcohol production, scrap recycling, and racketeering".[55]As a result, many Zainichi Koreans ended up living in slums or hamlets, a situation aided by Japanese real estate agents' refusal to let Zainichi Koreans rent houses.[55]

In addition to labor exploitation and housing discrimination, Koreans also endured significant social discrimination. They were segregated into specific neighborhoods, commonly referred to as "Korean Towns," (which still exist today inShin-ŌkuboandIkuno-ku) where living conditions were poor, sanitation was inadequate, and access to public services like healthcare and education was severely limited. Korean children faced bullying and discrimination in schools, which often led to high dropout rates and limited their educational and, subsequently, economic opportunities.[54]

Despite these adversities, the Zainichi community has fought for their rights and has seen gradual improvements in their status in Japan. Changes in legal and social recognition began to emerge towards the late 20th century, influenced by both domestic advocacy by human rights groups and international pressure.[56]

Zainichi today have established a stable presence in Japan after years of activism. ThroughMintohren,community support by Zainichi organizations (Mindan andChongryon,among others), other minority groups (Ainu,burakumin,Ryūkyūans,Nivkhs,and others), and sympathetic Japanese, the social atmosphere for Zainichi in Japan has improved. There are also Koreans living in Japan who try to present themselves as Japanese to avoid discrimination.[57]Most younger Zainichi now speak only Japanese, go to Japanese schools, work for Japanese firms, and increasingly marry Japanese people. Mostnaturalizationoccurs among the young during the period when they seekformal employmentor marriage. Those who have already established their lives increasingly do not choose to retain their South Korean orJoseonnationality or heritage and lead average lives alongside other Japanese. This, as well as marriage to Japanese nationals, is leading to a sharp decrease in the original "Zainichi" population in Japan.

Assimilation

[edit]One of the most pressing issues of the Zainichi community is the rate ofassimilationof Zainichi into Japan. About 4,000 to 5,000 Koreans naturalize in Japan every year out of slightly less than 480,000.[58]Naturalization carries a crucial cultural aspect in Japan, as both Mindan and Chongryon link Korean ethnic identity to Korean nationality, and Japanese and South Korean nationality laws do not allow multiple citizenship for adults. By their definition, opting for a Japanese passport means becoming Japanese, rather than Korean-Japanese.

In order to be naturalized as Japanese citizens, Zainichi Koreans previously had to go through multiple, complex steps, requiring collection of information about their family and ancestors stretching back ten generations. This information could be collected through a Korean organization such as Mindan, but with their prohibitively expensive cost, many were unable to afford it. However, these processes have become much easier, and today, it is easier for Zainichi Koreans to naturalize into Japanese citizens.[citation needed]

Though there are a few cases of celebrities who naturalize with their Korean name, the majority of naturalized Zainichi Koreans formally choose a name that is both read and appears ethnically Japanese. This supports the aforementioned cultural implication of naturalisation, leading some to take the rate of naturalisation as a rough measure of assimilation.[citation needed]

During the post-World War II period, many Zainichi Koreans married with other Zainichi Koreans, and it was a rare case for them to intermarry with Japanese citizens. This was because of Japanese xenophobic prejudice against Zainichi Koreans due to stigma stemming from decades of discrimination. Therefore, Japanese citizens, especially their parents, largely refused marriage with Zainichi Koreans. However, there were problems with marriage between Zainichi Koreans, too. As stated in the previous section, Zainichi Koreans were mostly hiding their identity and living as Japanese-presenting people at the time. Because of this, it was very hard for Zainichi Koreans to connect with other people who had the same nationality as them. They were married mostly through arranged marriages supported by Mindan.[55]

Tong-il Ilbo(통일일보), orTōitsu Nippō(Thống nhất nhật báo), a Korean-Japanese newspaper, reported that according to statistics from the Japanese Health and Labour ministry, there were 8,376 marriages between Japanese and Koreans.[when?]Compared to 1,971 marriages in 1965, when the statistics began, the number has roughly quadrupled, and it now constitutes about 1% of the 730,971 total marriages in Japan. The highest annual number of marriages between Japanese men and Korean women was 8,940, in 1990. Since 1991, it has fluctuated around 6,000 per year. On the other hand, there were 2,335 marriages between Korean men and Japanese women in 2006. It has been stable since the number reached 2,000 per year in 1984.[59]

In 1975, Hidenori Sakanaka (Bản trung anh đứcSakanaka Hidenori), a bureaucrat in theMinistry of Justice,published a highly controversial document known as the "Sakanaka Paper". He stated that the assertion by both Mindan and Chongryon that Zainichi are destined to eventually return to Korea is no longer realistic. He further predicted that Zainichi would naturally disappear in the 21st century unless they abandon their link between Korean identity and Korean nationality. He argued that the Japanese government should stop treating Zainichi as temporary residents (with aspecial status) and start providing a proper legal framework for their permanent settlement as "Korean Japanese".

In December 1995,Gendai Korea( "Modern Korea") published the article," 20 years after the Sakanaka Paper "to assess further development.[citation needed]The article pointed out that in the 1980s, 50% of Zainichi Koreans married Japanese, and in the 1990s, the rate was 80%. (In fact, they quoted only 15–18% Korean marriage during 1990 to 1994.) They also pointed out the change in the law in 1985, which granted Japanese citizenship to a child with either parent being Japanese—previous laws granted citizenship only to a child with a Japanese father. In practice, this would mean that less than 20% of Zainichi marriages would result in Zainichi status. According to the article, since naturalisation is concentrated among the younger generation, the Zainichi population should be expected to collapse once the older generation starts to die out in two decades.

The latest figures from Mindan showed that the total population of Zainichi was 598,219 in 2006 and 593,489 in 2007, and that only 8.9% married another Zainichi in 2006. There were 1,792 births and 4,588 deaths, resulting in a 2,796 natural decrease. On top of that, there were 8,531 naturalisations, which resulted in a total decrease of 11,327 in 2006 (2%).[60]

Registration of residents

[edit]After Zainichi Koreans lost Japanese nationality, the Immigration Control Act of 1951 and the Alien Registration Law of 1952 required them to be fingerprinted and to carry a certificate of registration as other foreigners did. The Permanent Residents by Accord of 1965 allowed Zainichi Koreans who had lived in Japan since the colonial period to apply for permanent residency, but their descendants could not. Twenty-six years later, theJapanese Dietpassed the Special Law on Immigration Control and categorized Zainichi Koreans who have lived without any gap since the end of World War II or before and their lineal descendants asSpecial Permanent Residents.[61]The fingerprint requirement for Zainichi Koreans was terminated by 1993.[14]

Right to vote and government employment

[edit]Long-term ethnic Korean residents of Japan who have not taken up Japanese nationality currently have the legal status ofTokubetsu Eijusha( "Special Permanent Residents" )and are granted special rights and privileges compared to other foreigners, especially in matters such as re-entry and deportation statutes. These privileges were originally given to residents with South Korean nationality in 1965, and were extended in 1991 to cover those who have retained their Korean nationality.

Over the decades, Zainichi Koreans have been campaigning to regain their Japanese citizenship rights without having to adopt Japanese nationality. The right to claimsocial welfarebenefits was granted in 1954, followed by access to the national health insurance structures (1960s) and state pensions (1980s). There is some doubt over the legality of some of these policies, as the Public Assistance Law, which governs social welfare payments, is seen to apply only to "Japanese nationals".

There has been discussion about Zainichi South Koreans' right to vote inSouth Korea.SinceSpecial Permanent Residentsare exempted from military service and taxes, the South Korean government was reluctant to give them the right to vote, arguing they did not register as residents, though it thought most people agree on granting the right to vote to short-stay South Korean travelers. On the other hand, Zainichi South Koreans claimed that they should be granted it because theConstitution of South Koreaguarantees anyone having South Korean nationality the right to vote.[62]In 2007, theConstitutional Court of Koreaconcluded all South Korean nationals don't have the right to vote in South Korea if they are permanent residents of other countries.[63][64]

Zainichi North Koreans are allowed to vote and theoretically eligible to stand inNorth Korea'sshow electionsif they are 17 years old or older.[65]

There have also been campaigns to allow Zainichi Koreans to take up government employment and participate in elections, which are open to Japanese nationals only. Since 1992,Mindanhas been campaigning for the right to vote in elections for prefectural and municipal assemblies, mayors, and prefecture governors, backed by the South Korean government. In 1997,Kawasakibecame the first municipality to hire a Korean national. So far, three prefectures—Osaka,Nara,andKanagawa—have supported voting rights for permanent foreign residents.

However, the Japanese Diet has not yet passed a resolution regarding this matter, despite several attempts by a section within theLiberal Democratic Party of Japanto do so, and there is considerable public and political opposition against granting voting rights to those who have not yet adopted Japanese nationality. Instead, the requirements for naturalization have been steadily lowered for Zainichi to the point that only criminal records or affiliation toNorth Koreawould be a hindrance for naturalization. Both Zainichi organisations oppose this, as both see naturalization asde factoassimilation. In November 2011, the South Korean government moved to register Zainichi Koreans as voters in South Korean elections, a move which attracted few registrants. While Mindan-affiliated Zainichi Koreans have pressed for voting rights in Japan, they have very little interest in becoming avoting blocin South Korean politics.Chongryonfor its part opposes moves to allow Zainichi Koreans to participate in Japanese politics, on the grounds that they assimilate Koreans into Japanese society and thus weaken Korean ethnic identity.[66]

Korean schools

[edit]

The pro-North Korea association Chongryon operates 218Chōsen gakkōacross Japan, including kindergartens and one university,Korea University.All lessons and all conversations within the school are conducted inKorean.They teach a strong pro-North Korean ideology and allegiance toKim Il Sung,Kim Jong Il,andKim Jong Un.The textbooks include an idealized depiction of the economic development of North Korea andSongunpolicy of Kim Jong Il.[67]

One of the issues the schools now face is a lack of funding. The schools were originally set up and run with support from the North Korean government, but this money has now dried up, and with dropping pupil numbers, many schools are facing financial difficulties.[citation needed]The Japanese government has refused Chongryon's requests that it fund ethnic schools in line with regular Japanese schools, citing Article 89 of theJapanese Constitution,where use of public funds for education by non-public bodies is prohibited. In reality, the schools are in fact partly funded by local authorities, but subsidies are given in the form of special benefits paid to the families of pupils, as opposed to paying the schools directly, in order to avoid a blatant breach of Article 89. It is still much less than the amount received by state schools.

Another issue is an examination called the High School Equivalency Test, ordaiken,which qualifies those who have not graduated from a regular high school to apply for a place in a state university and take an entrance exam. Until recently, only those who had completed compulsory education (i.e., up to junior high school) were entitled to take thedaiken.This meant pupils of ethnic schools had to complete extra courswork before being allowed to take the exam. In 1999, the requirement was amended so that anyone over a certain age is qualified. Campaigners were not satisfied because this still meant graduates of non-Japanese high schools had to take thedaiken.In 2003, the Education Ministry removed the requirement to take the Equivalency Test from graduates of Chinese schools, Mindan-run Korean schools, and international schools affiliated with Western nations and accredited by U.S. and British organizations. However, this did not apply to graduates of Chongryon-run Korean schools, as the minisitry said it could not approve their curricula. The decision was left up to individual universities, 70% of which allowed all Korean school graduates to apply directly.[68]

Due to the issues described above, the number of students at Korean schools run by Chongryon has declined by 67%, and many of the children of Zainichi Koreans now choose to go to orthodox Japanese schools.[69]

There are a fewKankoku Gakkō(Korean:한국학교/ Hàn Quốc trường học,Japanese:Hàn Quốc trường học) located in Tokyo, Osaka,Ibaraki,Kyoto,andIshioka,which receive sponsorship from South Korea and are operated by Mindan. Koreans who live in Japan and support South Korea are likely to attend aKankoku gakkō.Alternatively, they may go to a normal school in Japan taught in Japanese. Most Koreans who have lived in Japan since they were born, however, go to normal schools even if there is aKankoku gakkōnear them.[70]

Legal alias

[edit]| Legal alias | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Japanese name | |||||||

| Kanji | Xưng tên | ||||||

| Kana | つうめい | ||||||

| |||||||

| North Korean name | |||||||

| Chosŏn'gŭl | 통명 | ||||||

| Hancha | Xưng tên | ||||||

| |||||||

Registered aliens in Japan are allowed to adopt aregistered alias(Thường gọi danh,tsūshōmei),often abbreviated totsūmei(Xưng tên,"common name" ),as their legal name.[71]Traditionally, Zainichi Koreans have used Japanese-style names in public, but some Zainichi Koreans, including celebrities and professional athletes, use their original Korean names. Well-known ethnic Koreans who use Japanese names includeHanshin TigersstarTomoaki Kanemoto,pro wrestlersRiki ChoshuandAkira Maeda,and controversialjudokaandmixed martial artistYoshihiro Akiyama.

During theKorea-Japan 2002 FIFA World Cup,a Mindan newspaper conducted a survey regarding the use of aliases. 50% of those polled said that they always use an alias, while 13% stated they always use their original name. 33% stated that they use either depending on the situation.[72][73]In a 1986 survey, over 90% of ethnic Koreans in Japan reported having a Japanese-sounding name in addition to a Korean one.[74]In a 1998 study, 80% stated that they used their Japanese names when in Japanese company, and 30% stated that they used their Japanese names "almost exclusively".[75]

Zainichi in the Japanese labor market

[edit]

Zainichi Koreans are said to mainly be employed inpachinkoparlors, restaurants/bars, and construction.[76]Discrimination against Zainichi Koreans in hiring has pushed many into so-called3D(dirty, dangerous, and demeaning) industries.[77]Annual sales ofpachinkohave totaled about 30 trillionyensince 1993, and Zainichi Koreans have accounted for 90% of such sales.[78]However, thepachinkoindustry is shrinking, because the Japanese government has imposed stricter regulations. The number ofpachinkoparlors decreased by 9–10% between 2012 and 2016, while the number of people playingpachinkodropped to less than 9.4 million.[79]

Some Zainichi Koreans have developedyakinikurestaurants.[14]The honorary president of theAll Japan "Yakiniku" Associationis Tae Do Park (alias Taido Arai).[80][81]

In the 1970s, Korean newcomers started to enter theprecious metalsindustry. Currently, 70% ofprecious metalsproducts in Japan are made by certified Zainichi Koreans.[82]

Some Zainichi Koreans participate in organized crime, as do people in other segments of the population. A former member of theyakuzagroupSumiyoshi-kaiestimated there are a few hundred Koreanyakuza,and that some of them are Boss es of branches. However, the member went on to say that Korean gang members tend to go to China and Southeast Asia, as these countries are more lucrative for them than Japan.[83]

There has been improvement in the working rights of Zainichi Koreans since the 1970s.[84]For example, foreigners including Zainichi Koreans were previously not allowed to become lawyers in Japan, but Kim Kyung Deok became the first Zainichi Korean lawyer in 1979. As of 2018, there are more than 100 Zainichi Korean lawyers in Japan, and some of them have worked as members of LAZAK (Lawyers Association of Zainichi Koreans).[85]

In popular culture

[edit]The earliest Japanese films featuring Koreans in Japan often depicted Koreans as members of the peripheral society, rather than as main characters. It wasn't until after the Second World War that films visualized the struggles and oppression experienced by Zainichi Koreans, with films such asThree Resurrected Drunkards(1968) byNagisa Ōshima,which addressed the bigotry and xenophobia experienced by Zainichi in Japan. The first film to present the Zainichi experience from a Zainichi director was the 1975 filmRiver of the Strangerby Lee Hak-in.

Zainichi directorYoichi Sai'sAll Under the Moonwas the first to receive critical acclaim, earning several best film awards in 1993. In 2001, Zainichi directorLee Sang-ilreleased his first film,Chong,and in 2001, Zainichi authorKazuki Kaneshiro'sNaoki Prize-winning bookGO(2000), about a North Korean Zainichi, was made into a popularfilm of the same name.Yang Yong-hiwould be the first to address theChongryonexperience in a documentary, withDear Pyongyangin 2005.

Korean Americancreatives have used the Zainichi experience to parse their own experience as part of the greaterKorean diaspora,with films such asBenson Lee's 2016 filmSeoul Searching,and authorMin Jin Lee's 2017 novelPachinko.Pachinkotells the story of several generations of Zainichi Koreans and the prevailing stereotype within Japan about Koreans andpachinkoparlors; the book explores themes of belonging, nationality, and longstanding political debates about discrimination and xenophobia against Koreans in Japan. The novel has been made into a limitedTV series of the same namebyApple TV+.[86][87]

Notable people

[edit]See also

[edit]- The History Museum of J-Koreans

- Koreatowns in Japan

- Sōshi-kaimei

- Kantō Massacre

- Shinano River incident

- Demography of Japan

- Ethnic issues in Japan

- Japan–Korea disputes

- Japan–North Korea relations

- Japan–South Korea relations

- Japanese people in South Korea

- List of Koreans in Japan

- History of Japan–Korea relations

- Anti-Korean sentiment in Japan

- Racism in Japan

- Hanshin Education Incident

- Koma Shrine

- Koryo-Saram

Other ethnic groups in Japan

[edit]References

[edit]- ^Lệnh cùng 5 năm mạt hiện tại における ở lưu người nước ngoài số について

- ^ab"Ở lưu người nước ngoài thống kê ( cũ đăng lục người nước ngoài thống kê ) ở lưu người nước ngoài thống kê nguyệt thứ 2023 năm 6 nguyệt | ファイル | thống kê データを thăm す".

- ^Statistics Bureau, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications (July 2021)."Quốc tịch ・ địa vực đừng ở lưu tư cách ( ở lưu mục đích ) đừng ở lưu người nước ngoài"[Foreigners by nationality and by visas (occupation)].

- ^Hester, Jeffry T. (2008). "Datsu Zainichi-ron: An emerging discourse on belonging among Ethnic Koreans in Japan". In Nelson H. H.; Ertl, John; Tierney, R. Kenji (eds.).Multiculturalism in the new Japan: crossing the boundaries within.Berghahn Books. p.144–145.ISBN978-1-84545-226-1.

- ^Diamond, Jared (June 1, 1998)."In Search of Japanese Roots".Discover Magazine.

- ^Fukuoka, Yasunori; Gill, Tom (2000).Lives of young Koreans in Japan.Trans-Pacific Press. p.xxxviii.ISBN978-1-876843-00-7.

- ^Lệnh cùng 5 năm mạt hiện tại における ở lưu người nước ngoài số について

- ^"【 ở lưu người nước ngoài thống kê ( cũ đăng lục người nước ngoài thống kê ) bảng thống kê 】 | xuất nhập quốc ở lưu quản lý sảnh".

- ^Ryang, Sonia; Lie, John (2009-04-01)."Diaspora without Homeland: Being Korean in Japan".Escholarship.org\accessdate=2016-08-17.

The same threat hung over thousands more who had arrived as refugees from the massacres that followed the April 3, 1948, uprising on Jeju Island and from the Korean War.

- ^1988Ở Nhật Bản đại Hàn dân quốc thanh niên sẽ 『アボジ nghe かせて あ の ngày の ことを — ta 々 の lịch sử を lấy り lệ す vận động báo cáo thư — 』 “Trưng binh ・ trưng dùng 13.3%” “そ の hắn 20.2%”, “Không rõ 0.2%” “Kinh tế lý do 39.6%” “Kết hôn ・ thân tộc と の sống chung 17.3%” “Lưu học 9.5%”

- ^"가라포고이".Encyclopedia of Korean Culture.

- ^Tamura, Toshiyuki."The Status and Role of Ethnic Koreans in the Japanese Economy"(PDF).Institute for International Economics.RetrievedNovember 19,2017.

- ^Arents, Tom; Tsuneishi, Norihiko (December 2015)."The Uneven Recruitment of Korean Miners in Japan in the 1910s and 1920s: Employment Strategies of the Miike and Chikuhō Coalmining Companies".International Review of Social History.60(S1): 121–143.doi:10.1017/S0020859015000437.ISSN0020-8590.S2CID147292906.

- ^abcd"FSI | SPICE – Koreans in Japan".spice.fsi.stanford.edu.Retrieved2017-11-20.

- ^Tamura, Toshiyuki."The Status and Role of Ethnic Koreans in the Japanese Economy"(PDF).Institute for International Economics.RetrievedNovember 19,2017.

- ^Kimura, Kan."Tổng lực chiến thể chế kỳ の Triều Tiên bán đảo に quan する một khảo sát ― người động viên を trung tâm にして―"(PDF).Ngày Hàn lịch sử cộng đồng nghiên cứu báo cáo thư. Đệ 3 phân khoa thiên hạ quyển.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 2014-04-06.

- ^"ExEAS – Teaching Materials and Resources".columbia.edu.Retrieved2017-11-20.

- ^Rummel, R. J. (1999).Statistics of Democide: Genocide and Mass Murder Since 1990.Lit Verlag.ISBN3-8258-4010-7. Available online:"Statistics of Democide: Chapter 3 – Statistics Of Japanese Democide Estimates, Calculations, And Sources".Freedom, Democracy, Peace; Power, Democide, and War.Retrieved2006-03-01.

- ^Lankov, Andrei (2006-01-05)."Stateless in Sakhalin".The Korea Times.Archived fromthe originalon 2006-02-21.Retrieved2006-11-26.

- ^Quang ngạn, mộc thôn (2016)."Nhật Bản đế quốc と đông アジア"(PDF).Institute of Statistical Research.[permanent dead link]

- ^"【そ の khi の hôm nay 】 “Ở ngày Triều Tiên người” bắc đưa sự nghiệp が thủy まる | Joongang Ilbo | trung ương nhật báo ".japanese.joins(in Japanese).Retrieved2017-11-20.

- ^Chiêu cùng 27 năm 02 nguyệt 27 ngày 13- tham - địa phương hành chính ủy linh mộc một の phát ngôn “Một tạc năm の mười tháng から nhập quốc quản lý sảnh が phát đủ いたしまして ước một năm gian の gian に 3000 trăm 90 danh という Triều Tiên người を đưa り quy しておる. Nay の mật nhập quốc の hơn phân nửa は, chín 〇%は Triều Tiên người でございます”

- ^"asahi: Khảo vấn ・ chiến tranh ・ độc tài trốn れ… Ở ngày nữ tính 60 năm ぶり tế châu đảo に quy hương へ – xã hội".2008-04-01. Archived fromthe originalon 2008-04-01.Retrieved2017-11-20.

- ^Sa la, phác (November 25, 2013)."Cảnh giới を cụ thể hoá する chiếm lĩnh kỳ Nhật Bản へ の “Mật hàng” からみる nhập quốc quản lý chính sách と “Người nước ngoài” khái niệm の lại biên ( Digest_ muốn ước ) "(PDF).Kyoto University Research Information Repository.RetrievedNovember 19,2017.

- ^Chiêu cùng 25 năm 11 nguyệt 01 ngày 8- chúng - ngoại vụ ủy “Triều Tiên người の mật nhập quốc は đối mã を trung tâm といたしまして, そ の chu biên の các huyện にまたがる địa vực が áp đảo con số を kỳ しており, đại thể cả nước tổng số の bảy cắt ないし tám cắt が cùng phương diện によつて chiếm められているという trạng huống であります.”

- ^"Mật hàng 4ルート の động thái ngày Hàn kết ぶ hải の đường phố lẻn vào はお trà の こ bắt わる giả chỉ か2 cắt".Sản nghiệp kinh tế tin tức.June 28, 1950.

- ^Yoshida Shigeru = Makkāsā ōfuku shokanshū 1945–1951.Sodei, Rinjirō, 1932–, tay áo giếng Lâm Nhị Lang, 1932– (Shohan ed.). Tōkyō: Hōsei Daigaku Shuppankyoku. 2000.ISBN4588625098.OCLC45861035.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: others (link) - ^abcRyang, Sonia (2000)."The North Korean homeland of Koreans in Japan".In Sonia Ryang (ed.).Koreans in Japan: Critical Voices from the Margin.Taylor & Francis.ISBN978-1-136-35312-3.

- ^United Nations International Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Racial Discrimination(September 26, 2000): "E. Korean residents in Japan 32. The majority of Korean residents, who constitute about one third of the foreign population in Japan, are Koreans (or their descendants) who came to reside in Japan for various reasons during the 36 years (1910–1945) of Japan's rule over Korea and who continued to reside in Japan after having lost Japanese nationality, which they held during the time of Japan's rule, with the enforcement of the San Francisco Peace Treaty (28 April 1952)."

- ^Trường đảo, vạn dặm tử (April 2011)."Hàn Quốc の lưu học sinh chính sách とそ の 変 dời"(PDF).ウェブマガジン『 lưu học giao lưu 』.1:1–10. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 2021-07-04.Retrieved2017-12-16.

- ^ab"Trưởng thành kỳ を nghênh えた thật lớn lữ hành thị trường 『 Trung Quốc 』へ の アプローチ ( 2 ) 2009/01/23( kim ) 13:56:13 [サーチナ]".archive.fo.2012-07-13. Archived from the original on 2012-07-13.Retrieved2017-11-20.

{{cite news}}:CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^"Hàn Quốc người へ の ngắn hạn ビザ miễn trừ を vĩnh cửu hóa – nikkansports".nikkansports(in Japanese).Retrieved2017-11-20.

- ^"' tân ・ cũ ' ở ngày Hàn Quốc người dân đoàn とど の ように quan わるか dân đoàn trung ương đại hội を trước にしたオールドカマー・ニューカマー の thanh ".One Korea Daily News.February 18, 2009. Archived fromthe originalon January 14, 2012.Alt URL

- ^zenaplus.jp."재일본한국인연합회".haninhe.Retrieved2017-11-20.

- ^ab"Mapping Out the Cultural Politics of 'the Korean Wave' in Contemporary South Korea".East Asian Pop Culture.2008. pp. 175–189.doi:10.5790/hongkong/9789622098923.003.0010.ISBN978-962-209-892-3.

{{cite book}}:Unknown parameter|name=ignored (help) - ^"Japan's Declining Population: Clearly a Problem, But What's the Solution?".WilsonCenter.org.Retrieved2024-04-18.

- ^Terao, Gorō (April 1959).38 độ tuyến の bắc[North of the 38th Parallel] (in Japanese). Tân Nhật Bản nhà xuất bản.ASINB000JASSKK.

- ^Morris-Suzuki, Tessa (2005-02-07)."Japan's Hidden Role In The 'Return' Of Zainichi Koreans To North Korea".ZNet. Archived fromthe originalon 2007-03-17.Retrieved2007-02-14.

The motives behind the official enthusiasm for repatriation are clearly revealed by Masutaro Inoue, who described Koreans in Japan as being "very violent," [6] "in dark ignorance," [7] and operating as a "Fifth Column" in Japanese society.... Inoue is reported as explaining that the Japanese government wanted to "rid itself of several tens of thousands of Koreans who are indigent and vaguely communist, thus at a stroke resolving security problems and budgetary problems (because of the sums of money currently being dispensed to impoverished Koreans)

- ^Morris-Suzuki, Tessa (2007-03-13)."The Forgotten Victims of the North Korean Crisis".Nautilus Institute. Archived fromthe originalon 2007-09-27.Retrieved2007-03-15.

{{cite journal}}:Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^Moon, Rennie."FSI -Koreans in Japan".

- ^Nozaki, Yoshiki; Inokuchi Hiromitsu; Kim Tae-Young."Legal Categories, Demographic Change and Japan's Korean Residents in the Long Twentieth Century".Japan Focus.Archived fromthe originalon 2007-01-25.

- ^"Spy's escape from North Korean 'hell'".BBC News.2003-01-06.Retrieved2007-03-16.

- ^"2006 Sundance Film Festival announces awards for documentary and dramatic films in independent film and world cinema competitions"(PDF)(Press release). Sundance Film Festival. 2006-01-28.Retrieved2007-03-20.

- ^"1970, South Korea refused forced displacement of Korean residents in Japan who perpetrated a crime"(Press release). Yomiuri Shimbun. 2008-02-12. Archived fromthe originalon 2009-02-21.Retrieved2008-02-12.

- ^Shin, Eunju."ソウル の dị bang người, そ の chu biên một Lý cấn chi “Từ hi” をめぐって "[Portrait of a Foreigner's World in Seoul: Yuhi by Yi Yangji)](PDF).Niigata University of International and Information Studies. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 2007-06-16.

{{cite journal}}:Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^"Yonhap News".Archived fromthe originalon 2006-10-03.Retrieved2006-10-10.

- ^(in Japanese)Abe Shunji,The Home-coming Movement Seen from North Korea: An Interview with Mr. Oh Gi-Wan, the Former Member of the Reception Committee for Japan's Korean ReturneesArchived2007-11-03 at theWayback Machine,Bulletin of Faculty of Education, Nagasaki University. Social science,Nagasaki University, Vol. 61 (20020630) pp. 33–42.ISSN0388-2780

- ^"FM Spokesman Urges Japan to Stop Suppression of Chongryon".Korea-np.co.jp.Archived fromthe originalon 2011-02-10.Retrieved2016-08-17.

- ^"CBSi".FindArticles.Archived fromthe originalon 2011-02-08.Retrieved2016-08-17.

- ^Corrected: Pro-Pyongyang group rules out link to abductionArchived2007-03-22 at theWayback Machine(Asian Political News,November 18, 2002)

- ^"Japan Considered Podcast for April 7, 2006 Volume 2, Number 14".Archived fromthe originalon 2006-09-12.Retrieved2006-12-12.

- ^N Korea ferry struggling against the tide(BBC News Online, June 9, 2003)

- ^Tsutsui, K., & Shin, H. J. (2008). "Global Norms, Local Activism, and Social Movement Outcomes: Global Human Rights and Resident Koreans in Japan".Social Problems,(3). 391.doi:10.1525/sp.2008.55.3.391.

- ^abRyang, Sonia, ed. (2006).Koreans in Japan: critical voices from the margin.RoutledgeCurzon studies in Asia's transformations (Transferred to digital print ed.). London: Routledge.ISBN978-0-415-37939-7.

- ^abcMin, Ganshick.Zainichi Kankokujin no Genjou to Mirai(Present lives and Future of Zainichi Koreans). Tokyo: Hirakawa Print Press, 1994.[ISBN missing][page needed]

- ^Lie, John (2009).Zainichi (Koreans in Japan): diasporic nationalism and postcolonial identity.Global, area, and international archive (Nachdr. ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press.ISBN978-0-520-25820-4.

- ^"Caste, Ethnicity and Nationality: Japan Finds Plenty of Space for Discrimination".Hrdc.net.2001-06-18.Retrieved2016-08-17.

- ^Qua đi 10 trong năm の quy hóa cho phép xin giả số, quy hóa cho phép giả số chờ の chuyển dời(in Japanese).Retrieved2021-08-15.

- ^Nhật Bản の cuộc sống giàu có 労 động tỉnh の điều べによると, 2006 năm だけで, Hàn Quốc ・ Triều Tiên tịch sở hữu giả と nước Nhật tịch giả の gian で kết ばれた hôn nhân kiện số は8376 kiện を số える. Điều tra を bắt đầu した1965 năm の 1971 kiện に so べ, およそ4 lần で, nước Nhật nội toàn thể の hôn nhân kiện số 73 vạn 971 kiện の うち, ước 1%を chiếm めている. Ở ngày Hàn Quốc ・ Triều Tiên người nữ tính と Nhật Bản người nam tính gian の hôn nhân kiện số が nhất も nhiều かった の は90 năm の 8940 kiện. 91 năm lấy hàng は6000 kiện trước sau に lưu まっており, 06 năm mạt hiện tại では6041 kiện を số えた. Nửa mặt, Hàn Quốc ・ Triều Tiên người nam tính と Nhật Bản người nữ tính gian の hôn nhân kiện số は06 năm mạt hiện tại で2335 kiện. 1984 năm に2000 kiện を siêu えて tới nay, ほぼ hoành ばい trạng thái だ.

- ^"Mindan".mindan.org.Archived fromthe originalon February 23, 2008.

- ^Tamura, Toshiyuki."The Status and Role of Ethnic Koreans in the Japanese Economy"(PDF).Institute for International Economics.RetrievedNovember 19,2017.

- ^"재외국민에 참정권 부여 않는건 위헌?".Munhwa Ilbo.Retrieved2017-11-20.

- ^Bạch giếng, kinh (September 2009)."Hàn Quốc の công chức tuyển cử pháp sửa lại ― ở nước ngoài dân へ の tuyển cử 権 giao cho"(PDF).Quốc lập quốc hội đồ thư quán điều tra cập び lập pháp khảo tra cục.

- ^チャン, サンジン (June 29, 2007)."Hiến pháp tài, ở nước ngoài dân の tham chính 権 chế hạn に vi hiến phán quyết".Chusun Online.Archived fromthe originalon July 4, 2007.

- ^"〈 tối cao nhân dân hội nghị đại nghị viên tuyển cử 〉 giải thích Triều Tiên の tuyển cử đứng đợi bổ から được tuyển まで".Triều Tiên tân báo.

- ^"Moves to legislate on" suffrage "in Japan condemned".Korean Central News Agency.2000-03-22. Archived fromthe originalon 2014-10-12.Retrieved2007-07-10.

- ^"Review and Prospect of Internal and External Situations"(PDF).Moj.go.jp.Retrieved2016-08-17.

- ^"Child Research Net CRN – Child Research in Japan & Asia – Recent Research on Japanese Children – Ed-Info Japan –".Archived fromthe originalon 2011-02-10.Retrieved2010-06-15.

- ^Shipper, Apichai (2010)."Nationalisms of and Against Zainichi Koreans in Japan"(PDF).Asian Politics & Policy.2:55–75.doi:10.1111/j.1943-0787.2009.01167.x.

- ^"'Center of Ethnic Education' Tokyo Korea School, Tokyo Kankoku gakko, 'When we need more support from South Korea'".THE FACT JPN. 2013-12-09.Retrieved2017-11-14.

- ^Zainichi (Koreans in Japan): Diasporic Nationalism and Postcolonial Identity.John Lie.University of California Press, 15 Nov 2008

- ^"Quốc tế: Ngày Hàn giao lưu".asahi.Archived fromthe originalon 2002-02-24.Retrieved2016-08-17.

- ^"Dân đoàn /BackNumber/トピック8".Mindan.org.Archived fromthe originalon 2001-08-02.Retrieved2016-08-17.

- ^Kimpara, S., Ishida, R., Ozawa, Y., Kajimura, H., Tanaka, H. and Mihashi, O. (1986) Nihon no Naka no Kankoku-Chosenjin, Chugokujin: Kanagawa-kennai Zaiju Gaikokujin Jittai Chosa yori (Koreans and Chinese Inside Japan: Reports from a Survey on Foreign Residents of Kanagawa Prefecture), Tokyo: Akashi Shoten.

- ^Japanese Alias vs. Real Ethnic Name: On Naming Practices among Young Koreans in Japan. Yasunori Fukuoka (Saitama University, Japan). ISA XIV World Congress of Sociology (July 26 – August 1, 1998, Montreal, Canada)

- ^Ở ngày コリアン の 2 tín dụng tổ hợp が3 nguyệt xác nhập nghiệp giới 12 vị に(in Japanese).Retrieved2017-11-20.

- ^Yim, Young-Eon (December 2008)."The Study on Categorization of Japanese-Korean Entrepreneurs by their Motivation for Entrepreneurship"(PDF).Lập mệnh quán quốc tế địa vực nghiên cứu.28:111–129. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 2016-03-04.Retrieved2017-12-18.

- ^"Nhật Bản, パチンコ phát tài chính nguy cơ? | Joongang Ilbo | trung ương nhật báo".japanese.joins(in Japanese).Retrieved2017-11-20.

- ^"パチンコ nghiệp giới, bổn cách suy yếu が thủy まった… Các xã hiên cũng み bán thượng kích giảm, “Ra ngọc quy chế” が truy い đánh ち – ビジネスジャーナル/Business Journal | ビジネス の bổn âm に bách る ".ビジネスジャーナル/Business Journal | ビジネス の bổn âm に bách る(in Japanese).Retrieved2017-11-20.

- ^Hiệp hội điểm chính.Cả nước thiêu thịt hiệp hội All-Japan "Yakimiki" Association(in Japanese).Retrieved2017-11-20.

- ^"< ở ngày xã hội > ở ngày tân thế kỷ ・ tân たな tòa tiêu trục を cầu めて 23 ― cao cấp thiêu thịt cửa hàng “Tự 々 uyển” kinh 営こ の nói ひと gân 50 năm tân giếng thái nói さん ― | ở ngày xã hội | ニュース | Đông Dương kinh tế nhật báo ".toyo-keizai.co.jp(in Japanese).Retrieved2017-11-20.

- ^"Ở ngày kim loại quý hiệp luận bàn 30 năm の lịch sử quang る… Tức bán sẽ rầm rộ".mindan.org.Archived fromthe originalon 2016-12-28.Retrieved2017-11-20.

- ^Hàn Quốc người bạo lực đoàn viên Nhật Bản に mấy trăm người? = chức vị quan trọng gánh うことも.Liên hợp ニュース(in Japanese).Retrieved2017-11-20.

- ^Cho, Young-Min (2016)."Koreans in Japan: a Struggle for Acceptance, Law School International Immersion Program Papers, No. 2 (2016)".Law School International Immersion Program Papers.2.

- ^Lawyers Association of Zainichi Koreans (LAZAK) (March 30, 2017)."Discrimination Against Koreans in Japan: Japan's Violation of its International Human Rights Obligation".United Nations Human Rights Council: Universal Periodic Review Third Cycle – Japan – Reference Documents.RetrievedDecember 1,2018.

- ^Chang, Justin (23 January 2015)."Sundance Film Review: 'Seoul Searching'".Variety.Retrieved20 September2020.

- ^Aw, Tash (2017-03-15)."Pachinko by Min Jin Lee review – rich story of the immigrant experience".The Guardian.Retrieved2021-08-20.

Further reading

[edit]- Kim-Wachutka, Jackie (2005).Hidden Treasures: Lives of First-Generation Korean Women in Japan.Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.ISBN0-7425-3595-9.

- Kim-Wachutka, Jackie (2019).Zainichi Korean Women in Japan: Voices.London: Routledge.ISBN978-1-138-58485-3.

- Morris-Suzuki, Tessa (2007).Exodus to North Korea: Shadows from Japan's Cold War.Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.ISBN978-0-7425-7938-5.

External links

[edit]- FCCJ (The Foreign Correspondents' Club of Japan) Mr. Suganuma of former Public Security Investigation Agency tells it about Zainichi Korean(Japanese, English)

- South Korean Residents Union in Japan (Mindan)(Korean, Japanese, English)

- History of Mindan(English)

- Online Newspaper covering Zainichi Korean and Mindan(English)

- The Federation of Korean Associations, Japan(Korean, Japanese)

- North Korean Residents Union in Japan (Joseon Chongryon)(Korean, Japanese)

- The Han WorldArchived2004-11-15 at theWayback Machine– a site for Korean residents in Japan.

- The Self-Identities of Zainichi Koreans– a paper on Zainichi.

- MINTOHREN: Young Koreans Against Ethnic Discrimination in Japan

- Panel discussion in San FranciscoNichi Bei Times Article

- Testing Tolerance: Fallout from North Korea's Nuclear Program Hits Minorities in Japanarticle from The Common Language Project

- "From Korea to Kyoto; Chapter One of Community, Democracy, and Performance: the Urban Practice of Kyoto's Higashi-Kujo Madang

- Migration patterns of Korean residents in Ikuno ward, Osaka – Japanese Journal of Human Geography ( nhân văn địa lý )