Zhang Qian

Zhang Qian Trương khiên | |

|---|---|

Zhang Qian taking leave from emperorHan Wudi,for his expedition toCentral Asiafrom 138 to 126 BC,Mogao Cavesmural, 618 – 712... | |

| Born | 195 BC |

| Died | c. 114BC |

| Occupation | Explorer |

| Zhang Qian | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

"Zhang Qian" in Traditional (top) and Simplified (bottom) Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | Trương khiên | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | Trương khiên | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

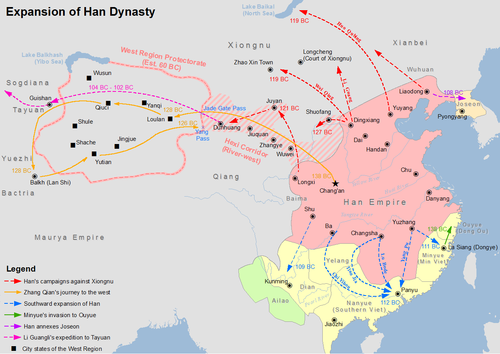

Zhang Qian(Chinese:Trương khiên;died c. 114 BC)[1]was a Chinese diplomat, explorer, and politician who served as an imperial envoy to the world outside of China in the late 2nd century BC during theWestern Han dynasty.He was one of the first official diplomats to bring back valuable information aboutCentral Asia,including theGreco-Bactrian remainsof theMacedonian Empireas well as theParthian Empire,to theHan dynastyimperial court, then ruled byEmperor Wu of Han.

He played an important pioneering role for the future Chinese conquest of lands west ofXin gian g,including swaths ofCentral Asiaand even lands south of theHindu Kush(seeProtectorate of the Western Regions). This trip created theSilk Roadthat marked the beginning of globalization between the countries in the east and west.[2][3][4][5]

Zhang Qian's travel was commissioned by Emperor Wu with the major goal of initiating transcontinental trade in the Silk Road, as well as create political protectorates by securing allies.[6]His missions opened trade routes between East and West and exposed different products and kingdoms to each other through trade. Zhang's accounts were compiled bySima Qianin the 1st century BC. TheCentral Asianparts of the Silk Road routes were expanded around 114 BC largely through the missions of and exploration by Zhang Qian.[7]Today, Zhang is considered a Chinese national hero and revered for the key role he played in opening China and the countries of the known world to the wider opportunity of commercial trade and global alliances.[8]Zhang Qian is depicted in theWu Shuang Pu( vô song phổ, Table of Peerless Heroes) by Jin Guliang.

Zhang Qian's Missions[edit]

Zhang Qian was born in Chenggu district just east ofHanzhongin the north-central province ofShaanxi,China.[9]He entered the capital, Chang'an, today'sXi'an,between 140 BC and 134 BC as a Gentleman (Lang), servingEmperor Wuof theHan dynasty.At the time the nomadicXiongnutribes controlled what is nowInner Mongoliaand dominated theWestern Regions,Xiyu (Tây Vực), the areas neighbouring the territory of the Han dynasty. The Han emperor was interested in establishing commercial ties with distant lands but outside contact was prevented by the hostile Xiongnu.[citation needed]

The Han court dispatched Zhang Qian, a military officer who was familiar with the Xiongnu, to theWestern Regionsin 138 BC with a group of ninety-nine members to make contact and build an alliance with theYuezhiagainst the Xiongnu. He was accompanied by a guide named Ganfu (Cam phụ), a Xiongnu who had been captured in war.[10]The objective of Zhang Qian's first mission was to seek a military alliance with theYuezhi,[11]in modernTajikistan.However to get to the territory of the Yuezhi he was forced to pass through land controlled by the Xiongnu who captured him (as well as Ganfu) and enslaved him for thirteen years.[12]During this time he married a Xiongnu wife, who bore him a son, and gained the trust of the Xiongnu leader.[13][14][15]

Zhang and Ganfu (as well as Zhang's Xiongnu wife and son) were eventually able to escape and, passingLop Norand following the northern edge of theTarim Basin,around theKunlun Mountainsand through small fortified areas in the middle of oases in what is nowXin gian guntil they made their way toDayuanand eventually to the land of the Yuezhi. The Yuezhi were agricultural people who produced strong horses and many unknown crops includingalfalfafor animalfodder.However, the Yuezhi were too settled to desire war against the Xiongnu. Zhang spent a year in Yuezhi and the adjacentBactrianterritory, documenting their cultures, lifestyles and economy, before beginning his return trip to China, this time following the southern edge of the Tarim Basin.[16] On his return trip he was again captured by the Xiongnu who again spared his life because they valued his sense of duty and composure in the face of death. Two years later the Xiongnu leader died and in the midst of chaos and infighting Zhang Qian escaped. Of the original mission of just over a hundred men, only Zhang Qian and Ganfu managed to return to China.[17][18]

Zhang Qian returned in 125 BC with detailed news for the Emperor, showing that sophisticated civilizations existed to the West, with which China could advantageously develop relations. The Shiji relates that "the Emperor learned of the Dayuan ( Ðại Uyên ), Daxia ( đại hạ ), Anxi ( an giấc ngàn thu ), and the others, all great states rich in unusual products whose people cultivated the land and made their living in much the same way as the Chinese. All these states, he was told, were militarily weak and prized Han goods and wealth".[19]Upon Zhang Qian's return to China he was honoured with a position of palace counsellor.[20]Although he was unable to develop commercial ties between China and these far-off lands, his efforts did eventually result in trade mission to theWusunpeople in 119 BC which led to trade between China andPersia.[21]

On his mission Zhang Qian had noticed products from an area now known asnorthern India.However, the task remained to find a trade route not obstructed by the Xiongnu to India. Zhang Qian set out on a second mission to forge a route from China to India viaSichuan,but after many attempts this effort proved unsuccessful. In 119–115 BC Zhang Qian was sent on a third mission by the emperor, to develop ties with theWusun(Ô tôn) people.[22][23]

Zhang Qian's reports[edit]

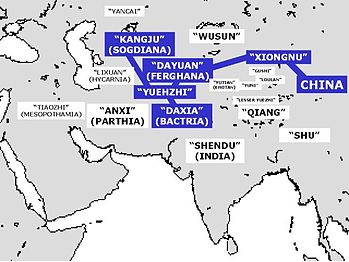

The reports of Zhang Qian's travels are quoted extensively in the 1st century BC Chinese historic chronicles "Records of the Great Historian" (Shiji) bySima Qian.Zhang Qian visited directly the kingdom ofDayuan(Ðại Uyên) inFergana,the territories of theYuezhi(Nguyệt Thị) inTransoxiana,theBactriancountry ofDaxia(Đại hạ) with its remnants ofGreco-Bactrianrule, andKangju(Khang cư). He also made reports on neighbouring countries that he did not visit, such as Anxi (An giấc ngàn thu) (Arsacidterritories), Tiaozhi ( điều chi / điều chi ) (Seleucid EmpireinMesopotamia), Shendu (Thân độc) (India) and theWusun(Ô tôn).[24]

Dayuan ( Ðại Uyên, Ferghana)[edit]

After being released from captivity by Xiongnu, Zhang Qian visitedDayuan,located in theFerganaregion west of theTarim Basin.The people of Dayuan were being portrayed as sophisticated urban dwellers similar to the Parthians and the Bactrians. The name Dayuan is thought to be a transliteration of the wordYona,the Greek descendants that occupied the region from the 4th to the 2nd century BCE. It was during this stay that Zhang reported the famous tall and powerful "blood-sweating"Ferghana horse.The refusal by Dayuan to offer these horses to Emperor Wu of Han resulted in twopunitive campaignslaunched by the Han dynasty to acquire these horses by force.[25]

- "Dayuan lies south-west of the territory of the Xiongnu, some 10,000li(5,000 kilometres) directly west of China. The people are settled on the land, ploughing the fields and growing rice and wheat. They also make wine out of grapes. The people live in houses in fortified cities, there being some seventy or more cities of various sizes in the region. The population numbers several hundred thousand "(Shiji,123, Zhang Qian quote, trans. Burton Watson).[26]

Later theHan dynastyconquered the region in theWar of the Heavenly Horses.[27]

Yuezhi ( Nguyệt Thị )[edit]

After obtaining the help of the king of Dayuan, Zhang Qian went south-west to the territory of theYuezhi,with whom he was supposed to obtain a military alliance against the Xiongnu.[28]

- "The Great Yuezhi live some 2,000 or 3,000 li (1,000 or 1,500 kilometres) west of Dayuan, north of the Gui (Oxus) river. They are bordered to the south by Daxia (Bactria), on the west byAnxi,and on the north byKangju ( khang cư ).They are a nation of nomads, moving place to place with their herds and their customs are like those of the Xiongnu. They have some 100,000 or 200,000 archer warriors. "(adapted fromShiji,123, Zhang Qian quote, trans. Burton Watson).

Zhang Qian also describes the origins of the Yuezhi, explaining they came from the eastern part of theTarim Basin.This has encouraged some historians to connect them to theCaucasoid mummies of the Tarim.(The question of links between the Yuezhi and theTochariansof the Tarim is still debatable.)[29]

- "The Yuezhi originally lived in the area between the Qilian or Heavenly Mountains (Tian Shan) andDunhuang,but after they were defeated by the Xiongnu they moved far away to the west, beyond Dayuan (Ferghana), where they attacked the people of Daxia (Bactria) and set up the court of their king on the northern bank of the Gui (Oxus) river. "(Shiji,123, Zhang Qian quote, trans. Burton Watson).

A smaller group of Yuezhi, the "Little Yuezhi", were not able to follow the exodus and reportedly found refuge among the "Qiangbarbarians ".

Zhang was the first Chinese to write about one humped dromedary camels which he saw in this region.[30]

Daxia ( đại hạ, Bactria)[edit]

Zhang Qian probably witnessed the last period of theGreco-Bactrian Kingdom,as it was being subjugated by the nomadic Yuezhi. Only small powerless chiefs remained, who were apparently vassals to the Yuezhi horde. Their civilization was urban, almost identical to the civilizations ofAnxiand Dayuan, and the population was numerous.

- "Daxia is situated over 2,000li(1,000 kilometres) south-west ofDayuan(Ferghana), south of the Gui (Oxus) river. Its people cultivate the land, and have cities and houses. Their customs are like those of Dayuan. It has no great ruler but only a number of petty chiefs ruling the various cities. The people are poor in the use of arms and afraid of battle, but they are clever at commerce. After the Great Yuezhi moved west and attacked and conquered Daxia, the entire country came under their sway. The population of the country is large, numbering some 1,000,000 or more persons. The capital is Lanshi (Bactra) where all sorts of goods are bought and sold. "(Shiji,123, Zhang Qian quote, translation Burton Watson).

Cloth from Shu (Sichuan) was found there.[31]

Shendu ( thân độc, India)[edit]

Zhang Qian also reports about the existence ofIndiasouth-east of Bactria. The nameShendu(Thân độc) comes from theSanskritword "Sindhu", meaning the Indus river. Sindh was at the time ruled byIndo-Greek Kingdoms,which explains the reported cultural similarity between Bactria and India:

- "Southeast of Daxia is the kingdom of Shendu (India)... Shendu, they told me, lies several thousandlisouth-east of Daxia (Bactria). The people cultivate the land and live much like the people of Daxia. The region is said to be hot and damp. The inhabitants ride elephants when they go in battle. The kingdom is situated on a great river (Indus) "(Shiji,123, Zhang Qian quote, trans. Burton Watson).

Anxi ( an giấc ngàn thu, Parthia)[edit]

Zhang Qian identifies "Anxi" (Chinese:An giấc ngàn thu) as an advanced urban civilization, like Dayuan (Ferghana) and Daxia (Bactria). The name "Anxi" is a transcription of "Arshak"(Arsaces),[32]the name of the founder ofArsacid Empirethat ruled the regions along the Silk Road between theTedzhen riverin the east and theTigrisin the west, and running throughAria,Parthiaproper, andMediaproper.

- "Anxi is situated several thousandliwest of the region of the Great Yuezhi. The people are settled on the land, cultivating the fields and growing rice and wheat. They also make wine out of grapes. They have walled cities like the people of Dayuan (Ferghana), the region contains several hundred cities of various sizes. The coins of the country are made of silver and bear the face of the king. When the king dies, the currency is immediately changed and new coins issued with the face of his successor. The people keep records by writing on horizontal strips of leather. To the west lies Tiaozhi (Mesopotamia) and to the north Yancai and Lixuan (Hyrcania). "(Shiji,123, Zhang Qian quote, trans. Burton Watson).

Tiaozhi ( điều chi, Seleucid Empire in Mesopotamia)[edit]

Zhang Qian's reports onMesopotamiaand theSeleucid Empire,or Tiaozhi (Điều chi), are in tenuous terms. He did not himself visit the region, and was only able to report what others told him.

- "Tiaozhi (Mesopotamia) is situated several thousandliwest of Anxi (Arsacidterritory) and borders the "Western Sea" (which could refer to thePersian GulforMediterranean). It is hot and damp, and the people live by cultivating the fields and planting rice... The people are very numerous and are ruled by many petty chiefs. The ruler of Anxi (the Arsacids) give orders to these chiefs and regards them as vassals. "(adapted fromShiji,123, Zhang Qian quote, trans. Burton Watson).

Kangju ( khang cư ) northwest of Sogdiana ( túc đặc )[edit]

Zhang Qian also visited directly the area ofSogdiana(Kangju), home to the Sogdian nomads:

- "Kangju is situated some 2,000 li (1,000 kilometres) north-west of Dayuan (Bactria). Its people are nomads and resemble the Yuezhi in their customs. They have 80,000 or 90,000 skilled archer fighters. The country is small, and borders Dayuan. It acknowledges sovereignty to the Yuezhi people in the South and the Xiongnu in the East." (Shiji, 123, Zhang Qian quote, trans. Burton Watson).

Yancai ( yểm Thái, Vast Steppe)[edit]

- "Yancai lies some 2,000li(832 km) north-west ofKangju(centered onTurkestanat Beitian). The people are nomads and their customs are generally similar to those of the people ofKangju.The country has over 100,000 archer warriors, and borders a great shore-less lake, perhaps what is now known as the Northern Sea (Aral Sea,distance betweenTashkenttoAralskis about 866 km) "(Shiji,123, Zhang Qian quote, trans. Burton Watson).

Development of East-West contacts[edit]

Following Zhang Qian's embassy and report, commercial relations between China and Central as well as Western Asia flourished, as many Chinese missions were sent throughout the end of the 2nd century BC and the 1st century BC, initiating the development of theSilk Road:

- "The largest of these embassies to foreign states numbered several hundred persons, while even the smaller parties included over 100 members... In the course of one year anywhere from five to six to over ten parties would be sent out." (Shiji, trans. Burton Watson).[33]

Many objects were soon exchanged, and travelled as far asGuangzhouin the East, as suggested by the discovery of aPersianbox and various artefacts from Central Asia in the 122 BC tomb of KingZhao MoofNanyue.[34]

Murals inMogao CavesinDunhuangdescribe the EmperorHan Wudi(156–87 BC) worshipping Buddhist statues, explaining them as "golden men brought in 120 BC by a great Han general in his campaigns against the nomads", although there is no other mention of Han Wudi worshipping the Buddha in Chinese historical literature.

China also sent a mission toAnxi,which were followed up by reciprocal missions from Parthian envoys around 100 BC:

- "When the Han envoy first visited the kingdom ofAnxi,the king of Anxi (theArsacidruler) dispatched a party of 20,000 horsemen to meet them on the eastern border of the kingdom... When the Han envoys set out again to return to China, the king of Anxi dispatched envoys of his own to accompany them... The emperor was delighted at this. "(adapted from Shiji, 123, trans. Burton Watson).

The Roman historianFlorusdescribes the visit of numerous envoys, includingSeres(Chinese or central Asians), to the first Roman EmperorAugustus,who reigned between 27 BC and 14:

- "Even the rest of the nations of the world which were not subject to the imperial sway were sensible of its grandeur, and looked with reverence to the Roman people, the great conqueror of nations. Thus evenScythiansandSarmatianssent envoys to seek the friendship of Rome. Nay, theSerescame likewise, and theIndianswho dwelt beneath the vertical sun, bringing presents of precious stones and pearls and elephants, but thinking all of less moment than the vastness of the journey which they had undertaken, and which they said had occupied four years. In truth it needed but to look at their complexion to see that they were people of another world than ours. "(" Cathay and the way thither ",Henry Yule).

In 97, the Chinese generalBan Chaodispatched an envoy toRomein the person ofGan Ying.

SeveralRoman embassies to Chinafollowed from 166, and are officially recorded in Chinese historical chronicles.

Final years and legacy[edit]

TheShijireports that Zhang Qian returned from his final expedition to the Wusun in 115 BC. After his return he "was honoured with the post of grand messenger, making him among the nine highest ministers of the government. A year or so later he died."[35]

"The indications regarding the year of his passing differ, but Shih Chih-mien (1961), p. 268 shows beyond doubt that he died in 113 B.C. His tomb is situated in Chang-chia ts'un Trương gia thôn near Ch'eng-ku...; during repairs carried out in 1945 a clay mold with the inscription bác vọng gia tạo [Home of the Bowang (Marquis)] was found, as reported by Ch'en Chih (1959), p. 162." Hulsewé and Loewe (1979), p. 218, note 819.

Other achievements[edit]

From his missions he brought back many important products, the most important beingalfalfaseeds (for growing horsefodder), strong horses with hard hooves, and knowledge of the extensive existence of new products, peoples and technologies of the outside world. He diedc.114 BC after spending twenty-five years travelling on these dangerous and strategic missions. Although at a time in his life he was regarded with disgrace for being defeated by the Xiongnu, by the time of his passing he had been bestowed with great honours by the emperor.[36][37][38]

Zhang Qian's journeys had promoted a great variety of economic and cultural exchanges between the Han dynasty and the Western Regions. Because silk became the dominant product traded from China, this great trade route later became known as theSilk Road.[39]

See also[edit]

Footnotes[edit]

- ^Loewe (2000),p. 688.

- ^"ZHANG QIAN, EXPLORER CENTRAL ASIA".

- ^"Zhang Qian — Pioneer of the Silk Road in History of China".

- ^"The Chinese Explorer Zhang Qian on a Raft".

- ^Higa, Kiyota (2015-01-01)."Legend of Silk Road pioneer lives on".

- ^Xia, Zhihou (2018-03-15)."Zhang Qian".Retrieved2021-03-01.

- ^Boulnois, Luce (2005).Silk Road: Monks, Warriors & Merchants.Hong Kong: Odyssey Books. p.66.ISBN962-217-721-2.

- ^"The History and Legacy of the Silk Road route".

- ^Silk Road: Monks, Warriors & Merchants on the Silk Road,p. 61. (2004) Luce Boulnois. Translated by Helen Loveday. Odyssey Books & Guides.ISBN962-217-720-4(Hardback);ISBN962-217-721-2(Paperback).

- ^Watson (1993), p. 231.

- ^Silk Road, North China,C. Michael Hogan, The Megalithic Portal, ed. Andy Burnham

- ^Frances Wood,"The Silk Road: Two Thousand Years in the Heart of Asia", 2002, University of California Press, 270 pagesISBN978-0-520-23786-5

- ^James A. Millward (2007).Eurasian crossroads: a history of Xin gian g.Columbia University Press. p. 20.ISBN978-0-231-13924-3.Retrieved2011-04-17.

- ^Julia Lovell (2007).The Great Wall: China Against the World, 1000 BC – AD 2000.Grove Press. p. 73.ISBN978-0-8021-4297-9.Retrieved2011-04-17.

- ^Yiping Zhang (2005).Story of the Silk Road.Năm châu truyền bá nhà xuất bản. p. 22.ISBN7-5085-0832-7.Retrieved2011-04-17.

- ^Watson (1993), p. 232.

- ^"Zhang Qian".

- ^Alfred J. Andrea; James H. Overfield (1998).The Human Record: To 1700.Houghton Mifflin. p. 165.ISBN0-395-87087-9.Retrieved2011-04-17.

- ^Watson (1993), chap. 123.

- ^Andrew Dalby,Dangerous Tastes: The Story of Spices,2000, University of California Press, 184 pagesISBN0-520-23674-2

- ^Garver, John W. (2006-12-11)."Twenty Centuries of Friendly Cooperation: The Sino-Iranian Relationship".

- ^Encyclopedia of China: The Essential Reference to China, Its History and Culture,p. 615. Dorothy Perkins. (2000). Roundtable Press Book.ISBN0-8160-2693-9(hc);ISBN0-8160-4374-4(pbk).

- ^Charles Higham (2004).Encyclopedia of ancient Asian civilizations.Infobase Publishing. p. 409.ISBN0-8160-4640-9.Retrieved2011-04-17.

- ^"The Expedition of Zhang Qian".

- ^Indian Society for Prehistoric & Quaternary Studies (1998).Man and environment, Volume 23, Issue 1.Indian Society for Prehistoric and Quaternary Studies. p. 6.Retrieved2011-04-17.

- ^"Famous Travelers On The Silk Road".

- ^Blackwood, Andy (2018-01-04)."The Heavenly Horses of the Han Dynasty".Retrieved2021-01-02.

- ^Qian, Sima."Zhang Qian's Western Expedition"(PDF).

- ^"Section 13 – The Kingdom of the Da Yuezhi Đại Nguyệt thị (the Kushans)".

- ^Chinese Recorder.Presbyterian Mission Press. 1875. pp. 15–.

- ^James M. Hargett (2006).Stairway to Heaven: A Journey to the Summit of Mount Emei.SUNY Press. pp. 46–.ISBN978-0-7914-6682-7.

- ^The Kingdom of Anxi

- ^"Heavenly horses of Ferghana".

- ^Adrienne Mayor (22 September 2014).The Amazons: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women across the Ancient World.Princeton University Press. pp. 422–.ISBN978-1-4008-6513-0.

- ^Watson (1993), p. 240.

- ^Watson (1993), pp. 231–239, 181, 231–241.

- ^Encyclopedia of China: The Essential Reference to China, Its History and Culture,pp. 614–615. Dorothy Perkins. (2000). Roundtable Press Book.ISBN0-8160-2693-9(hc);ISBN0-8160-4374-4(pbk).

- ^ Alemany, Agustí (2000).Sources on the Alans: A Critical Compilation.BRILL. p. 396.ISBN9004114424.Retrieved2008-05-24.

- ^

Asiapac Editorial, Chung gian g Fu, Liping Yang, Chung gian g Fu, Liping Yang (2006).Chinese History: Ancient China to 1911 – Google Book Search.Asiapace Books. p. 84.ISBN9789812294395.Retrieved2008-05-24.

{{cite book}}:CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

References[edit]

- Hulsewé, A. F. P. and Loewe, M. A. N., (1979).China in Central Asia: The Early Stage 125 BC – AD 23: an annotated translation of chapters 61 and 96 of the History of the Former Han Dynasty.Leiden: E. J. Brill.

- Loewe, Michael (2000). "Zhang Qian trương khiên".A Biographical Dictionary of the Qin, Former Han, and Xin Periods (220 BC – AD 24).Leiden: Brill. pp. 687–9.ISBN90-04-10364-3.

- Yü, Ying-shih(1986). "Han Foreign Relations". InTwitchett, Denis;Fairbank, John K.(eds.).The Cambridge History of China, Volume 1: The Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 B.C. – A.D. 220.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 377–462.

Further reading[edit]

- Yap, Joseph P, (2019). The Western Regions, Xiongnu and Han, from the Shiji, Hanshu and Hou Hanshu.ISBN978-1792829154