Headline

Theheadlineis the text indicating the content or nature of the article below it, typically by providing a form of brief summary of its contents.

The large typefront page headlinedid not come into use until the late 19th century when increased competition betweennewspapersled to the use of attention-getting headlines.

It is sometimes termed a newshed,a deliberate misspelling that dates from production flow duringhot typedays, to notify the composing room that a written note from an editor concerned a headline and should not beset in type.[1]

Headlines in English often use a set of grammatical rules known asheadlinese,designed to meet stringent space requirements by, for example, leaving out forms of the verb "to be" and choosing short verbs like "eye" over longer synonyms like "consider".

Production

[edit]

A headline's purpose is to quickly and briefly draw attention to the story. It is generally written by acopy editor,but may also be written by the writer, the page layout designer, or other editors. The most important story on the front pageabove the foldmay have a larger headline if the story is unusually important.The New York Times's21 July 1969 front page stated, for example, that "MEN WALK ON MOON",with the four words in gigantic size spread from the left to right edges of the page.[2]

In the United States, headline contests are sponsored by theAmerican Copy Editors Society,theNational Federation of Press Women,and many state press associations; some contests consider created content already published,[3]others are for works written with winning in mind.[4]

Typology

[edit]Research in 1980 classified newspaper headlines into four broad categories:questions,commands, statements, and explanations.[5]Advertisers and marketers classify advertising headlines slightly differently into questions, commands, benefits, news/information, and provocation.[6]

Research

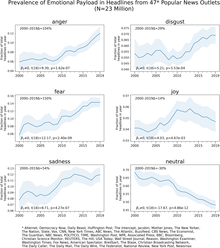

[edit]A study indicates there has been a substantial increase ofsentimentnegativity and decrease of emotional neutrality in headlines across written popular U.S.-basednews mediasince 2000.[8][7]

Skilled[clarify]newspaper readers "spend most of their reading time scanning the headlines—rather than reading [all or most of] the stories".[9]

Headlines can bias readers toward a specific interpretation and readers struggle to update their memory in order to correct initial misconceptions in the cases of misleading or inappropriate headlines.[10]

One approach investigated as a potentialcountermeasure to online misinformationis "attaching warnings to headlines of news stories that have been disputed by third-party fact-checkers", albeit its potential problems include e.g. that false headlines that fail to get tagged are considered validated by readers.[11]

Criticism

[edit]Sensationalism, inaccuracy and misleading headlines

[edit]This sectionneeds expansion.You can help byadding to it.(December 2022) |

"Slam"

[edit]The use of "slam" in headlines has attracted criticism on the grounds that the word is overused and contributes to mediasensationalism.[12][13]The violent imagery of words like "slam", "blast", "rip", and "bash" has drawn comparison toprofessional wrestling,where the primary aim is to titillate audiences with a conflict-laden and largely predetermined narrative, rather than provide authentic coverage of spontaneous events.[14]Journalists who use such words are widely considered to be lazy, uncreative, and unintelligent.

Crash blossoms

[edit]"Crash blossoms" is a term used to describe headlines that have unintended ambiguous meanings, such asThe Timesheadline "Hospitals named after sandwiches kill five". The word 'named' is typically used in headlines to mean "blamed/held accountable/named [in a lawsuit]",[15]but in this example it seems to say that the hospitals' names were related to sandwiches. The headline was subsequently changed in the electronic version of the article to remove the ambiguity.[16]The term was coined in August 2009 on the Testy Copy Editorsweb forum[17]after theJapan Timespublished an article entitled "Violinist Linked to JAL Crash Blossoms"[18](since retitled to "Violinist shirks off her tragic image" ).[19]

Headlinese

[edit]

Headlineseis an abbreviated form ofnews writing styleused innewspaperheadlines.[20]Because space is limited, headlines are written in a compressedtelegraphic style,using special syntactic conventions,[21]including:

- Forms of the verb "to be"andarticles(a,an,the) are usually omitted.

- Mostverbsare in thesimple presenttense, e.g. "Governor signs bill", while the future is expressed by aninfinitive,withtofollowed by a verb, as in "Governor to sign bill"

- Theconjunction"and" is often replaced by a comma, as in "Bush, Blair laugh off microphone mishap".[22]

- Individuals are usually specified by surname only, with nohonorifics.

- Organizations and institutions are often indicated bymetonymy:"Wall Street" for the US financial sector, "Whitehall" for the UK government administration, "Madrid" for the government of Spain, "Davos" for World Economic Forum, and so on.

- Manyabbreviations,includingcontractionsandacronyms,are used: in the UK, some examples areLib Dems(for theLiberal Democrats),Tories(for theConservative Party); in the US,Dems(for "Democrats") andGOP(for theRepublican Party,from the nickname "Grand Old Party" ). The period (full point) is usually omitted from these abbreviations, thoughU.S.may retain them, especially in all-caps headlines to avoid confusion with the wordus.

- Lack of a terminatingfull stop(period) even if the headline forms a complete sentence.

- Use ofsingle quotation marksto indicate a claim or allegation that cannot be presented as a fact. For example, an article titled "Ultra-processed foods 'linked to cancer'"covered a study which suggested a link but acknowledged that its findings were not definitive.[23][24]LinguistGeoffrey K. Pullumcharacterizes this practice as deceptive, noting that the single-quoted expressions in newspaper headlines are often not actual quotations, and sometimes convey a claim that is not supported by the text of the article.[25]Another technique is to present the claim as a question, henceBetteridge's law of headlines.[23][26]

Some periodicals have their own distinctive headline styles, such asVarietyand its entertainment-jargon headlines, most famously "Sticks Nix Hick Pix".

Commonly used short words

[edit]To save space and attract attention, headlines often use extremely short words, many of which are not otherwise in common use, in unusual or idiosyncratic ways:[27][28][29]

- ace(a professional, especially a member of an elite sports team, e.g. "Englandace ")

- axe(to eliminate)

- bid(to attempt)

- blast(to heavily criticize)

- cagers(basketball team – "cage" is an old term for indoor court)[30]

- chop(to eliminate)

- coffer(s)(a person or entity's financial holdings)

- confab(a meeting)[citation needed]

- eye(to consider)

- finger(to accuse, blame)

- fold(to shut down)

- gambit(an attempt)

- hail(to praise)

- hike(to increase, raise)

- ink(to sign a contract)

- jibe(an insult)

- laud(to praise)

- lull(a pause)

- mar(to damage, harm)

- mull(to contemplate)

- nab(to acquire, arrest)

- nix(to reject)

- parley(to discuss)

- pen(to write)

- probe(to investigate)

- rap(to criticize)

- romp(an easy victory or a sexual encounter)

- row(an argument or disagreement)

- rue(to lament)

- see(to forecast)

- slay(to murder)

- slam(to heavily criticize)

- slump(to decrease)

- snub(to reject)

- solon(to judge)

- spat(an argument or disagreement)

- star(acelebrity,often modified by another noun, e.g. "soapstar ")

- tap(to select, choose)

- tot(a child)

- tout(to put forward)

- woe(disappointment or misfortune)

Famous examples

[edit]Some famous headlines in periodicals include:

- WALL ST. LAYS AN EGG–VarietyonBlack Monday(1929)

- STICKS NIX HICK PIX–Varietywriting that rural moviegoers preferred urban films (1935)

- DEWEY DEFEATS TRUMAN–Chicago Tribunereporting the wrong election winner (1948)

- FORD TO CITY: DROP DEAD–New York Daily Newsreporting the denial of a federal bailout for bankruptNew York City(1975)

- MUSH FROM THE WIMP–The Boston Globein-house joke headline for an editorial, which was not changed before 161,000 copies had been printed. Theo Lippman Jr. of theBaltimore Sundeclared "Mush from the Wimp" the second most famous newspaper headline of the 20th century, behind "Wall St. Lays an Egg" and ahead of "Ford to City: Drop Dead".[31]

- HEADLESS BODY IN TOPLESS BAR–New York Poston a local murder (1983)[32]

- SICK TRANSIT'S GLORIOUS MONDAY–New York Daily Newsfront-page caption on a photo (1979) reporting an agreement to avoid fare increases on city transit services, making a multi-word pun on the Latin phraseSic transit gloria mundi[33]

- GOTCHA– The UKSunon the torpedoing of the Argentine shipBelgranoand sinking of a gunboat during theFalklands War(1982)

- FREDDIE STARR ATE MY HAMSTER– The UKSun(1986), claiming that the comedian had eaten a fan's pethamsterin a sandwich. The story was later proven false, but is seen as one of the classictabloid newspaperheadlines.[34]

- GREAT SATAN SITS DOWN WITH THE AXIS OF EVIL –The Times(UK) on US-Iran talks (2007)[35]

- SUPER CALEY GO BALLISTIC CELTIC ARE ATROCIOUS –SunonInverness Caledonian ThistlebeatingCeltic F.C.in the Scottish Cup;[36]a pun on "Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious"

- WE ARE POPE (in German:Wir sind Papst);Bildafter a German was voted to becomePope Benedict XVIin 2005.

The New RepubliceditorMichael Kinsleybegan a contest to find the most boring newspaper headline.[37]According to him, no entry surpassed the one that had inspired him to create the contest: "WORTHWHILE CANADIAN INITIATIVE",[38]over a column byThe New York Times'Flora Lewis.[39]In 2003,New York Magazinepublished a list of eleven "greatest tabloid headlines".[40]

See also

[edit]- A-1 Headline,a 2004 Hong Kong film

- Betteridge's law of headlines– Journalistic adage on questions in headlines

- Bus plunge,a type of news story, and accompanying headline

- Copy editing

- Corporate jargon

- Crosswordese,words common in crosswords that are otherwise rarely used

- Dateline– Piece of news text

- Ellipsis (linguistics),omission of words

- Headlines(fromThe Tonight Show with Jay Leno)

- Lead paragraph

- Nut paragraph– In journalism, an opening paragraph providing context for the story

- Syntactic ambiguity,leads to multiple humorous possible alternative interpretations of written headline

- Title (publishing)– Name of a published text or work of art

References

[edit]- ^NY Times: On Language: HED

- ^Wilford, John Noble (14 July 2009)."On Hand for Space History, as Superpowers Spar".The New York Times.Retrieved24 April2011.

- ^"Headline Contest".

- ^A NYTimes contest to write a NYPost-style headline"After Winning N.Y. Times Contest".The New York Times.November 11, 2011.

- ^Davis & Brewer 1997,p. 56.

- ^Arens 1996,p. 285.

- ^abcRozado, David; Hughes, Ruth; Halberstadt, Jamin (18 October 2022)."Longitudinal analysis of sentiment and emotion in news media headlines using automated labelling with Transformer language models".PLOS ONE.17(10): e0276367.Bibcode:2022PLoSO..1776367R.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0276367.ISSN1932-6203.PMC9578611.PMID36256658.

- ^Brooks, David (27 October 2022)."Opinion | The Rising Tide of Global Sadness".The New York Times.Retrieved21 November2022.

- ^Dor, Daniel (May 2003). "On newspaper headlines as relevance optimizers".Journal of Pragmatics.35(5): 695–721.doi:10.1016/S0378-2166(02)00134-0.S2CID8394655.

- ^Ecker, Ullrich K. H.; Lewandowsky, Stephan; Chang, Ee Pin; Pillai, Rekha (December 2014). "The effects of subtle misinformation in news headlines".Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied.20(4): 323–335.doi:10.1037/xap0000028.PMID25347407.

- ^Pennycook, Gordon; Bear, Adam; Collins, Evan T.; Rand, David G. (November 2020)."The Implied Truth Effect: Attaching Warnings to a Subset of Fake News Headlines Increases Perceived Accuracy of Headlines Without Warnings".Management Science.66(11): 4944–4957.doi:10.1287/mnsc.2019.3478.

- ^Ann-Derrick Gaillot (2018-07-28)."The Outline" slams "media for overusing the word".The Outline.Retrieved2020-02-24.

- ^Kehe, Jason (9 September 2009)."Colloquialism slams language".Daily Trojan.

- ^Russell, Michael (8 October 2019)."Biden 'Rips' Trump, Yankees 'Bash' Twins: Is Anyone Going to 'Slam' the Press?".PolitiChicks.

- ^Pérez, Isabel."Newspaper Headlines".English as a Second or Foreign Language.Retrieved31 March2020.

- ^Brown, David (18 June 2019)."Hospital trusts named after sandwiches kill five".The Times.Retrieved31 March2020.

- ^Zimmer, Ben (Jan 31, 2010)."Crash Blossoms".New York Times Magazine.Retrieved31 March2020.

- ^subtle_body; danbloom; Nessie3."What's a crash blossom?".Testy Copy Editors.Retrieved31 March2020.

{{cite web}}:CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^Masangkay, May (18 August 2009)."Violinist shirks off her tragic image".The Japan Times.Retrieved31 March2020.

- ^HeadlineseCollated definitions viawordnik

- ^Isabel Perez: "Newspaper Headlines"

- ^"Bush, Blair laugh off microphone mishap".CNN.July 21, 2006. Archived fromthe originalon August 16, 2007.RetrievedJuly 17,2007.

- ^abPack, Mark(2020).Bad News: What the Headlines Don't Tell Us.Biteback. p. 100-102.

- ^"Ultra-processed foods 'linked to cancer'".BBC News.2018-02-15.Retrieved2021-02-26.

- ^Pullum, Geoffrey (2009-01-14)."Mendacity quotes".Language Log.Retrieved2021-02-26.

- ^"The Secrets You Learn Working at Celebrity Gossip Magazines".2018-09-12.Retrieved2021-02-26.

- ^Chad Pollitt (March 5, 2019)."Which Types of Headlines Drive the Most Content Engagement Post-Click?".Social Media Today.

- ^"19 Headline Writing Tips for More Clickable Blog Posts".August 27, 2019.

- ^Ash Read (August 24, 2016)."There's No Perfect Headline: Why We Need to Write Multiple Headlines for Every Article".

- ^"When the Court was a Cage",Sports Illustrated

- ^Scharfenberg, Kirk (1982-11-06)."Now It Can Be Told... The Story Behind Campaign '82's Favorite Insult".The Boston Globe.Boston, Massachusetts.p. 1. Archived fromthe originalon 2011-05-23.Retrieved2011-01-20.(subscription required)

- ^Fox, Margalit (2016-06-09)."Vincent Musetto, 74, Dies; Wrote 'Headless' Headline of Ageless Fame".The New York Times.

- ^Daily News (New York), 9/25/1979, p. 1

- ^"Telegraph wins newspaper vote".BBC News. 25 May 2006.

- ^ Great Satan sits down with the Axis of Evil[dead link]

- ^"Super Caley dream realistic?".BBC. 22 March 2003.

- ^Kinsley, Michael (1986-06-02)."Don't Stop The Press".The New Republic.RetrievedApril 26,2011.

- ^Lewis, Flora (4 October 1986)."Worthwhile Canadian Initiative".The New York Times.Retrieved9 March2013.

- ^Kinsley, Michael (28 July 2010)."Boring Article Contest".The Atlantic.Retrieved26 April2011.

- ^"Greatest Tabloid Headlines".Nymag. March 31, 2003.Archivedfrom the original on January 22, 2009.RetrievedFebruary 11,2009.

Works cited

[edit]- Arens, William F. (1996).Contemporary Advertising.Irwin.ISBN978-0-256-18257-6.

- Davis, Boyd H.; Brewer, Jeutonne (1 January 1997).Electronic Discourse: Linguistic Individuals in Virtual Space.SUNY Press.ISBN978-0-7914-3475-8.

Further reading

[edit]- Harold Evans(1974).News Headlines(Editing and Design: Book Three) Butterworth-Heinemann Ltd.ISBN978-0-434-90552-2

- Fritz Spiegl(1966).What The Papers Didn't Mean to Say.Scouse Press, LiverpoolISBN0901367028

- Mårdh, Ingrid (1980);Headlinese: On the Grammar of English Front Page headlines;"Lund studies in English" series; Lund, Sweden: Liberläromedel/Gleerup;ISBN91-40-04753-9

- Biber, D. (2007); "Compressed noun phrase structures in newspaper discourse: The competing demands of popularization vs. economy"; in W. Teubert and R. Krishnamurthy (eds.);Corpus linguistics: Critical concepts in linguistics;vol. V, pp. 130–141; London: Routledge

External links

[edit]- Front Page – The British LibraryArchived2017-07-22 at theWayback MachineExhibition of famous newspaper headlines