Empayar Ottoman

Gamal

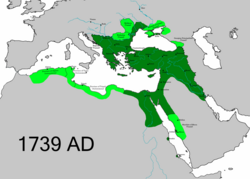

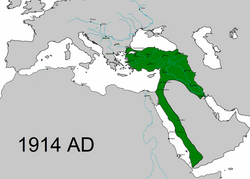

Empayar Ottoman,[lower-alpha 10]tau dikelala mega enggau namaEmpayar Turki,[24][25]ranah empayar[lower-alpha 11]bepalan baAnatoliati mungkur mayuh endur baEropah Tenggara,Asia Barat,enggauAfrika Utaraari abad ke-14 ngagai pun abad ke-20; iya mega nguasa sekeda endur ba tenggaraEropah Tengahentara pun abad ke-16 enggau pun abad ke-18.[26][27][28]

Penerang

[edit|edit bunsu]- ↑McDonald, Sean; Moore, Simon (2015-10-20)."Communicating Identity in the Ottoman Empire and Some Implications for Contemporary States".Atlantic Journal of Communication.23(5): 269–283.doi:10.1080/15456870.2015.1090439.ISSN1545-6870.S2CID146299650.Archivedfrom the original on 14 January 2023.Retrieved24 March2021.

- ↑Shaw, Stanford; Shaw, Ezel (1977).History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey.Vol. I. Cambridge University Press. p. 13.ISBN978-0-521-29166-8.

- ↑Atasoy & Raby 1989,p. 19–20.

- ↑4.04.1"In 1363 the Ottoman capital moved from Bursa to Edirne, although Bursa retained its spiritual and economic importance."Ottoman Capital BursaArchived5 Mac 2016 at theWayback Machine.Official website ofMinistry of Culture and Tourism of the Republic of Turkey.Retrieved 26 June 2013.

- ↑5.05.1Edhem, Eldem (21 May 2010). "Istanbul". In Gábor, Ágoston; Masters, Bruce Alan (eds.).Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire.Infobase. p.286.ISBN978-1-4381-1025-7.

With the collapse of the Ottoman Empire and the establishment of the Republic of Turkey, all previous names were abandoned and Istanbul came to designate the entire city.

- ↑Shaw, Stanford J.; Shaw, Ezel Kural (1977b).History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey.Vol. 2: Reform, Revolution, and Republic: The Rise of Modern Turkey 1808–1975. Cambridge University Press.doi:10.1017/CBO9780511614972.ISBN9780511614972.

- ↑Shaw & Shaw 1977b,p.386,volume 2;Robinson (1965).The First Turkish Republic.p. 298.;Society (2014-03-04)."Istanbul, not Constantinople"(in Inggeris). National Geographic Society. Archived fromthe originalon 7 July 2020.Retrieved2019-03-28.)

- ↑Inan, Murat Umut (2019). "Imperial Ambitions, Mystical Aspirations: Persian Learning in the Ottoman World". In Green, Nile (ed.).The Persianate World: The Frontiers of a Eurasian Lingua Franca.University of California Press. pp. 88–89.

As the Ottoman Turks learned Persian, the language and the culture it carried seeped not only into their court and imperial institutions but also into their vernacular language and culture. The appropriation of Persian, both as a second language and as a language to be steeped together with Turkish, was encouraged notably by the sultans, the ruling class, and leading members of the mystical communities.

- ↑Tezcan, Baki (2012). "Ottoman Historical Writing". In Rabasa, José (ed.).The Oxford History of Historical Writing: Volume 3: 1400-1800 The Oxford History of Historical Writing: Volume 3: 1400-1800.Oxford University Press. pp. 192–211.

Persian served as a 'minority' prestige language of culture at the largely Turcophone Ottoman court.

- ↑Flynn, Thomas O. (2017).The Western Christian Presence in the Russias and Qājār Persia, c.1760–c.1870(in Inggeris). BRILL. p. 30.ISBN978-90-04-31354-5.Archivedfrom the original on 14 January 2023.Retrieved21 October2022.

- ↑Fortna, B. (2012).Learning to Read in the Late Ottoman Empire and the Early Turkish Republic.Springer. p. 50.ISBN978-0-230-30041-5.Archivedfrom the original on 21 October 2022.Retrieved21 October2022.

Although in the late Ottoman period Persian was taught in the state schools...

- ↑Spuler, Bertold (2003).Persian Historiography and Geography.Pustaka Nasional Pte. p. 68.ISBN978-9971-77-488-2.Archivedfrom the original on 14 January 2023.Retrieved21 October2022.

On the whole, the circumstance in Turkey took a similar course: in Anatolia, the Persian language had played a significant role as the carrier of civilization. [...] where it was at time, to some extent, the language of diplomacy [...] However Persian maintained its position also during the early Ottoman period in the composition of histories and even Sultan Salim I, a bitter enemy of Iran and the Shi'ites, wrote poetry in Persian. Besides some poetical adaptations, the most important historiographical works are: Idris Bidlisi's flowery "Hasht Bihist", or Seven Paradises, begun in 1502 by the request of Sultan Bayazid II and covering the first eight Ottoman rulers...

- ↑Fetvacı, Emine (2013).Picturing History at the Ottoman Court.Indiana University Press.p. 31.ISBN978-0-253-00678-3.Archivedfrom the original on 21 October 2022.Retrieved21 October2022.

Persian literature, and belles-lettres in particular, were part of the curriculum: a Persian dictionary, a manual on prose composition; and Sa'dis 'Gulistan', one of the classics of Persian poetry, were borrowed. All these titles would be appropriate in the religious and cultural education of the newly converted young men.

- ↑Yarshater, Ehsan;Melville, Charles,eds. (359).Persian Historiography: A History of Persian Literature.Vol. 10. Bloomsbury. p. 437.ISBN978-0-85773-657-4.Archivedfrom the original on 21 October 2022.Retrieved21 October2022.

Persian held a privileged place in Ottoman letters. Persian historical literature was first patronized during the reign of Mehmed II and continued unabated until the end of the 16th century.

- ↑Inan, Murat Umut (2019). "Imperial Ambitions, Mystical Aspirations: Persian learning in the Ottoman World". InGreen, Nile(ed.).The Persianate World The Frontiers of a Eurasian Lingua Franca.University of California Press. p. 92 (note 27).

Though Persian, unlike Arabic, was not included in the typical curriculum of an Ottoman madrasa, the language was offered as an elective course or recommended for study in some madrasas. For those Ottoman madrasa curricula featuring Persian, see Cevat İzgi, Osmanlı Medreselerinde İlim, 2 vols. (Istanbul: İz, 1997),1: 167–69.

- ↑Ayşe Gül Sertkaya (2002). "Şeyhzade Abdurrezak Bahşı". In György Hazai (ed.).Archivum Ottomanicum.Vol. 20. pp. 114–115.Archivedfrom the original on 24 October 2022.Retrieved23 October2022.

As a result, we can claim thatŞeyhzade Abdürrezak Bahşıwas a scribe lived in the palaces of Sultan Mehmed the Conqueror and his son Bayezid-i Veli in the 15th century, wrote letters (bitig) and firmans (yarlığ) sent to Eastern Turks by Mehmed II and Bayezid II in both Uighur and Arabic scripts and in East Turkestan (Chagatai) language.

- ↑17.017.1Strauss, Johann (2010)."A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire: Translations of theKanun-ı Esasiand Other Official Texts into Minority Languages ".In Herzog, Christoph; Malek Sharif (eds.).The First Ottoman Experiment in Democracy.Würzburg:Orient-Institut Istanbul.pp. 21–51.Archivedfrom the original on 11 October 2019.Retrieved15 September2019.(info page on bookArchived20 September 2019 at theWayback MachineatMartin Luther University) // CITED: p. 26 (PDF p. 28): "French had become a sort of semi-official language in the Ottoman Empire in the wake of theTanzimatreforms.[...] It is true that French was not an ethnic language of the Ottoman Empire. But it was the only Western language which would become increasingly widespread among educated persons in all linguistic communities. "

- ↑Penyalat nyebut: Tag

<ref>tidak sah; tiada teks disediakan bagi rujukan yang bernamaLambton-1995 - ↑Ralat Lua pada baris 3162 di Modul:Citation/CS1: attempt to call field 'year_check' (a nil value).

- ↑20.020.120.2Rein Taagepera(September 1997)."Expansion and Contraction Patterns of Large Polities: Context for Russia".International Studies Quarterly.41(3): 498.doi:10.1111/0020-8833.00053.ISSN0020-8833.JSTOR2600793.Archivedfrom the original on 19 November 2018.Retrieved8 July2019.

- ↑Turchin, Peter; Adams, Jonathan M.; Hall, Thomas D (December 2006)."East-West Orientation of Historical Empires".Journal of World-Systems Research.12(2): 223.ISSN1076-156X.Archivedfrom the original on 20 May 2019.Retrieved12 September2016.

- ↑Erickson, Edward J. (2003).Defeat in Detail: The Ottoman Army in the Balkans, 1912–1913.Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 59.ISBN978-0-275-97888-4.

- ↑Strauss, Johann (2010)."A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire: Translations of theKanun-ı Esasiand Other Official Texts into Minority Languages ".In Herzog, Christoph; Malek Sharif (eds.).The First Ottoman Experiment in Democracy.Würzburg:Orient-Institut Istanbul.pp. 21–51.Archivedfrom the original on 11 October 2019.Retrieved15 September2019.(info page on bookArchived20 September 2019 at theWayback MachineatMartin Luther University) // CITED: p. 36 (PDF p. 38/338)

- ↑P., E. A. (1916)."Review of The Caliph's Last Heritage: A Short History of the Turkish Empire".The Geographical Journal.47(6): 470–472.doi:10.2307/1779249.ISSN0016-7398.JSTOR1779249.Archivedfrom the original on 10 July 2022.Retrieved10 July2022.

- ↑Baykara, Prof. Tuncer (2017)."A Study into the Concepts of Turkey and Turkistan which were used for the Ottoman State in XIXth Century".Journal of Atatürk and the History of Turkish Republic.1:179–190.Archivedfrom the original on 26 January 2024.Retrieved26 March2024.

- ↑Ingrao, Charles; Samardžić, Nikola; Pešalj, Jovan, eds. (2011-08-12).The Peace of Passarowitz, 1718.Purdue University Press.doi:10.2307/j.ctt6wq7kw.12.ISBN978-1-61249-179-0.JSTORj.ctt6wq7kw.Archivedfrom the original on 20 December 2023.Retrieved26 December2023.

- ↑Szabó, János B. (2019). "The Ottoman Conquest in Hungary: Decisive Events (Belgrade 1521, Mohács 1526, Vienna 1529, Buda 1541) and Results".The Battle for Central Europe(in Inggeris). Brill. pp. 263–275.doi:10.1163/9789004396234_013.ISBN978-90-04-39623-4.Retrieved2023-12-19.

- ↑Moačanin, Nenad (2019). "The Ottoman Conquest and Establishment in Croatia and Slavonia".The Battle for Central Europe(in Inggeris). Brill. pp. 277–286.doi:10.1163/9789004396234_014.ISBN978-90-04-39623-4.Archivedfrom the original on 15 January 2024.Retrieved2023-12-19.

Penyalat nyebut: Tag<ref>wujud untuk kumpulan bernama "lower-alpha", tetapi tiada tag<references group= "lower-alpha" />yang berpadanan disertakan

Kategori:

- Laman dengan ralat rujukan

- Pages using the JsonConfig extension

- Laman yang ada ralat skrip

- Harv and Sfn no-target errors

- Webarchive template wayback links

- CS1: long volume value

- CS1 Inggeris-language sources (en)

- Articles containing Ottoman Turkish (1500-1928)-language text

- Pages using infobox country or infobox former country with the flag caption or type parameters

- Pages using infobox country or infobox former country with the symbol caption or type parameters