विकासक्रम

जीवशास्त्रयविकासक्रमवा इभोलुसन धाःगु छगू प्रजातिया प्राणीया छगू पुस्तां मेगु पुस्ताय जैविक गुणय वइगु वंशानुगत हिउपा ख। थन्यागु हिउपा स्वंगु मू प्रक्रियां जुइगु या: भेरियसन (भिन्नता), प्रजनन व चयन। प्राणीइ दइगुजिनप्राणीतयेसं थःगु मस्तेत हस्तान्तरण याइ व थन्यागु जिनया अभिव्यक्तिं विकासक्रम न्ह्यथनि। थन्याःगु वंशानुगत गुण छगू जनसंख्याया दुने पाइ व प्राणीतयेगु गुणय्वंशानुगत भिन्नतादयाच्वनि। प्राणीतयेसं प्रजनन याइबिले इमिगु मचाय् मां-अबु स्वया पाःगु वा न्हुगु गुण दयेफु। थन्यागु वंशानुगत गुणय् भिन्नता निगु प्रक्रियां वयेफु- प्राणीया जिनय्म्युटेसनजुया वा जनसंख्या व प्रजातिया दथुइ जिनया बियेकाये ज्यां। मैथुनिय प्रजनन याइगु प्राणीइ जीनया न्हुगु मिश्रण आनुवंशीय पुनर्संयोजन (जेनेटिक रिकम्बिनेसनं) जुइफु गुकिलिं प्राणीतयेगु भिन्नता अप्वयका बी। सामान्य कथं थन्यागु प्रक्रियाया आवृत्ति अप्वसा वा म्हो जुसा विकासक्रम न्ह्यथनि।

प्राणीतयेगु विकासक्रम निगु मू पद्धतिं जुइ। प्रथम पद्धतिप्राकृतिक चयनख। थ्व प्रक्रियां याना वातावरणय् म्वायेत माःगु वंशानुगत गुण दुपिं प्राणी थःगु वातावरणय् बांलाक्क म्वाइ व अप्व मचा-खाचा दयेकि। थ्व कथं थन्यागु वंशानुगत गुण दुपिं प्राणीतयेगु जनसंख्या अप्वइ धाःसा वातावरणनाप मेल मजूगु गुण दुपिं प्राणीत बांलाक्क म्वायेखनि मखु, यक्व ल्वचं कइ व प्रजनन सापेक्षिक कथं म्हो जुइगुलिं बिस्तारं लोप जुजुं वनि व इमिगु वंशानुगत गुण बिस्तार म्हो जुया वनि।[१][२]थ्व प्रक्रिया न्थ्यथंगु यक्व ई व पुस्ता धुंकाअनूकुलनजुयावनि। अनूकुलन प्रक्रिया गुणय् लगातार चिधंगु अनिश्चित हिउपां न्ह्यथनि व थन्याःगु ह्युपाय् प्राकृतिक चयन जुया वातावरणय् झन् बांलाक्क म्वायेफूगु प्राणीतयेगु पुचःतयेगु जनसंख्या अप्वइ।[३]

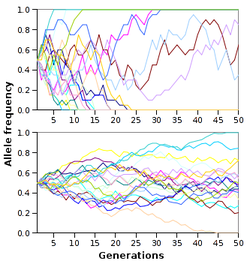

विकासक्रमया मेगु मू प्रक्रियाआनुवंशिक प्रवाह(जेनेटिक ड्रिफ्ट) ख। थ्व छगू स्वतन्त्र प्रक्रिया ख गुकिलिं छगू जनसंख्याय् गुणया आवृत्तिइ अनिश्चित हिउपा हइ। प्राणीत म्वाना प्रजनन याइबिले छगू निश्चित वंशानुगत गुण इमिगु सन्ततिइ हस्तान्तरण जुइगु संभावताया लिच्वया कथं आनुवंशिक प्रवाह जुइ। छगू पुस्ताय् प्रहावय् वैगु हिउपा म्हो जुसां पुस्तौं-पुस्ताय् थन्यागु हे म्हो हिउपा मुना वं-वं यक्व समय धुंका प्राणीइ तधंगु हिउपा वै। थन्यागु हिउपाया मंकांप्राणीया न्हुगु प्रजातिदया वै।[४]आ तक्क लूगु सकल प्राणीतयेगु संरचनाया अध्ययनं सकल प्राणी छगू हे प्रकारया प्राणीं उत्त्पत्ति जूया आनुवंशिक प्रवाहया कारणं भिन्नता दयावःगु धैगु खं क्यं।[१]

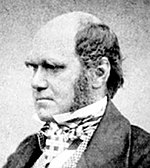

विकासक्रमीय जीवविज्ञानया विज्ञतयेसं विकासक्रमया तथ्यात्मक दस्ताबेज दयेकिगु व थन्यागु तथ्यया कारण व्याख्या याइगु सिद्धान्ततयेगु परिक्षण याइगु ज्या याइ। विकासक्रमीय जीवशास्त्रया सीकेज्या मध्य-१९गु शताब्दीइ न्ह्यथंगु ख। थ्व ईले जीवाश्म (fossil)तयेगु अध्ययन व जैविक विविधताया सीकेज्यां यक्व वैज्ञानिकतयेत प्रजातित समयनाप हिलावनि धैगु खंया छुमा बिल।[५][६]तर प्रजातितयेगु भिन्नता व हिलावनिगु प्रक्रियाया बारेय् छुं विचा न्ह्यने वःसां मूलप्रवाह वैज्ञानिकतयेगु तर्क व प्रयोगं अन्यागु विचातयेत गलत प्रमाणित यानाबिल। सन् १८५९इ स्व॰चार्ल्स डार्विनयाअन द ओरिजिन अफ स्पिसिजनांया सफू पिथन व् अथ्व सफूलि विकासक्रम प्राकृतिक चयनं जुइगु विचा न्ह्यथन।[७]डार्विनया विचायात तत्कालीन वैज्ञानिक समुदायं अत्याधिक रुपय् समर्थन यात।[८][९][१०][११]सन् १९३०या दशकय् डार्विनया प्राकृतिक चयनया सिद्धान्तयात ग्रेगर मेण्डलया इन्हेरिटेन्स सिद्धान्त नाप स्वाना आधुनिक विकासक्रमीय सिन्थेसिस दयेकेज्या जुल[१२]गुकिलिं विकासक्रमया इकाइ (जीन)यात विकासक्रमया प्रकृया (प्राकृतिक चयन)नाप स्वानाबिल। थ्व शक्तिशाली व्याख्यात्मक व निर्धारात्मक सिद्धान्तं विकासक्रमया मालेज्यायात निर्देशित याइगु जक मखुसें आधुनिक जीवशास्त्रया जैविक विविधताया केन्द्रिय संयोजक सिद्धान्तया रुपय् पलिस्था जुया च्वंगुदु।[९][१०][१३]

वंशानुगत[सम्पादन]

प्राणीइ इभोलुसन वंशानुगतगुणय् वइगु हिउपां जुइ। दसुया निंतिं मनुयामिखाया रंगछगू वंशानुगत गुण ख। थ्व गुण मनुतयेसं थःगु मां-अबुया गुणं इन्हेरिट याइ।[१४]इन्हेरिट याःगु गुणतजीनया नियन्त्रणय् दै व छगू प्राणीय् दइगु सकल जीनोमया सेटयात प्राणीया जिनोटाइप धाइ।[१५]

प्राणीया संरचना व व्यवहार दयेकिगु व खनेदैगु गुणतयेगु छगू पूर्ण सेटयात प्राणीयाफेनोटाइपधाइ। थन्याःगु गुण प्राणीया वारावरण नापया अन्तरक्रियां निर्माण जुइ।[१६]मेगु कथं धायेगु खःसा प्राणीया एक्स्प्रेस जूगु जीनतयेगु पुचःया पूवंगु सेट हे प्राणीया फेनोटाइप ख। फेनोटाइप वातावरण कथं पाइगु जूगुलिं सकल प्राणीतयेगु फेनोटाइप पाइ। दसुया निंतिं निभाले च्वना हाकुइगु धाःगु निभाया जलं मनुया छ्यंगुलि लाइबिले मनुया छ्यंगुलि दइगु मेलानोसाइटतयेसं मेलानिन धाःगु हाकूगु पदार्थ पिकाना जुइगु प्रक्रिया ख। छगू हे जीन दुपिं मनुत (दसु आइडेन्टिकल ट्विन्स)नं छम्ह निभाले जक्क च्वन व मेम्ह निभा मदूगु थासय् च्वन धाःसा (मेलानिन दयेकेज्याय् छुं व्याधि मदुसा) निभाले च्वनिम्ह जुडुवा, छगू हे जीन दसां मेम्ह स्वया हाकुइ। अथे जुसां हानं निभाया गुलि जलं मनु गुलि हाकुइगु धइगु परिमाण धाःसा हानं मनुया जीनं हे निर्धारण याइ। दसुया निंतिं छुं मनुइ मेलानोसाइटं मेलानिन हे दयेकिमख्। थन्यापिं मनुतयेसंअल्बिनिजमधाःगु गुण इन्हेरिट याइ। थन्याःगु गुण इन्हेरिट यापिं मनुतयेगु छ्यंगु न्ह्याक्वः निभाले च्वंसा भुइसे हे च्वनि। मेलानिन मदूगुलिं जःया विकिरणं याइगु विध्वंसात्मक प्रक्रियां थन्यापिं मनुतयेत अप्व असर याइ।[१७]

वंशानुगत गुण छगू पुस्तां मेगु पुस्ताय्डिएनएधाःगु छगूमोलेक्युलया मार्फतं थ्यनि। थ्व मोलेक्युलय् जेनेटिक सूचंया सूत्र स्वथनाच्वंगु दै।[१५]डिएनए धाःगु छगूपोलिमरख। थ्व पोलिमरय् प्यंगु प्रकारयाबेसदै। डिएनएय् दैगु बेसतयेगु सिक्वेन्सं जेनेटिक सूचं निर्धारण याइ। थ्व प्रक्रिया छगू खँग्वल्य् आखःया सिक्वेन्सं खँग्वःया अर्थ निर्धारण याइगु थें हे ख। छगू फंक्सनल युनिट दयेकिगु डिएनए मोलेक्युलया सिक्वेन्सयातजीनधाइ। थी-थी जीनया थी-थी बेस सिक्वेन्स दै। सेल बायोलोजीइ डिएनएया छगू ताःहाकःगु कन्डेन्स्ड संरचनायात क्रोमोजम धाइ। छगू क्रोमोजमया निश्चित थाय्यातलोकसधाइ। छगू लोकसय् डिएनएया सिक्वेन्स मनुदथुइ पाःसा उकियातएलिलधाइ। अतः, एलिल धाःगु क्रोमोजमया छगू हे निश्चित थासय् दइगु व छगू हे ज्या याइगु जीन (दसु मिखाया रंग बीगु जीन)या थी-थी प्रकार ख। डिएनए श्रृङ्खलाय्म्युटेसनजुया एलिलय् हिउपा वयेफु। थथे म्युटेसन वःसा न्हुगु एलिलं प्राणीया फेनोटाइप वंशानुगत फेनोटाइप स्वया हिलाछ्वये फु।

एलिल व गुणया थ्व साधारण अन्तरक्रिया छुं थासय् पाय्छि जुसां यक्व गुण थ्व साधारण अन्तरक्रिया स्वया जटिल प्रक्रियांयक्व जीनया अन्तरक्रियांनिर्धारण जुइ व सकल जीनया छुं भूमिका दःसां अन्ततः वैगु गुण धाःसा सकलया अन्तरक्रियाया लिच्वः जुइ।[१८][१९]थन्याःगु जटिल गुणतयेगु सीकेज्या धाःसा आःया समयया जेनेटिक मालेज्याया छगू मू ख्यः ख। जेनेटिक्सया छगू मेगु आजुचाइगु ख्यःइपिजेनेटिक्सख गुकिलि वंशानुगत गुणय् जीनय् हिउपा मवेकःहे प्राणीया वंशानुगत गुणय् हिउपा वै। थ्व ख्यः नं जेनेटिक्सया छगू मू मालेज्याया ख्यः ख।[२०]

भिन्नता[सम्पादन]

छम्ह प्राणीयाफेनोटाइपप्राणीयाजेनोटाइपव वातावरणया अन्तरक्रियाया लिच्वः ख। फेनोटाइपया भिन्नता आपालं जेनोटाइपया भिन्नताया लिच्व ख।[१९]आधुनिक विकासक्रम संश्लेषणया परिभाषा कथं विकासक्रम वा इभोलुसन धाःगु जेनेटिक भिन्नताय् समयनाप वइगु हिउपा ख। छगू प्रकारया एलिलया फ्रिक्वेन्सी समय नाप पाना वनि व मेमेगु एलिलया तुलनाय् सापेक्षिक रुपय् वातावरणनापया अन्तरक्रियाया लिच्वःया कथं पाइ। विकासक्रम थ्व हे एलिलया फ्रिक्वेन्सीया हिउपा व म्युटेसनया आधारय् न्ह्यने बढेजुइ। भिन्नता सामान्यतया उपस्थित जुसां छगू एलिलफिक्सेसनया फुतिइ थ्यन वा छगू एलिल बाहेक मेगु एलिल दक्वं नास जुयावन धाःसा तनावनि।[२१]

भिन्नताआनुवंशिक पदार्थय् (genetic material) म्युटेसन, प्राणीया जनसंख्याया स्थानान्तरणं जुइगु जीन बहाव (gene flow) वमैथुनिक प्रजननंजुइगु जिनया फेरबदल (reshuffling)या लिच्वःया कथं वै। भिन्नता, विशेषयानाएककोशिकप्राणीइ थी-थी प्राणीतयेगु दथुइ जुइगु जीन हिजेज्यां नं वै। दसु ब्याक्टेरियाय् जुइगुक्षैतिज जिन प्रदान(horizontal gene transfer) व स्वांमाय् याइगु वर्ण संकरन प्रक्रिया (hybridization)।[२२]थन्यागु प्रविधिं निरन्तर रुपय् भिन्नता हयातःसां छगू प्रजातिया आपालंजेनोमव हे प्रजातिया मेमेपिं प्राणीतनाप मेल न।[२३]नापं, जेनोटाइपय् म्हो जक्क हिउपा वःसां फेनोटाइपय् नाटकीय रुपान्तरण जुइ। दसुया निंतिं चिम्पाञ्जी व मनुया जेनोम ५% जक्क पा तर चिम्पाञ्जी व मनुतयेगु फेनोटाइप यक्व हे पा।[२४]

म्युतेसन[सम्पादन]

जेनेतिक भिन्न्ता प्राणीतयेगु जेनोमय् जुइगु अक्रमिक (random) म्युतेसनया लिच्वः ख। म्युतेसन धाःगु थी-थी कारणं (दसु- विकिरण, भाइरस, त्रान्स्पोजोन, म्युताजेनिक रसायन, मायोसिस व दिएनए रेप्लिकेसनय् जुइगु गलती आदि) प्राणीया दिएनए सिक्वेन्सय् वैगु परिवर्तन ख।[२५][२६][२७]म्युतेसन याकिगु तत्त्वयात म्युताजेन धाइ। थन्यागु म्युतेसनं दिएनए सिक्वेन्सय् थी-थी कथंया परिवर्तन हयेफु। म्युताजेन्सं छुं असर मयायेगु, जीनया उत्पादयात स्यंकिगु, जीनयात ज्या यायेमबिगु आदि हिउपा हयेफु। म्युतेसनं आपालं ध्वंसात्मक हिउपा हैगुलिं प्राणीतयेसं म्युतेसन म्हो यायेत थी-थी विकासक्रमात्मक पद्दति दयेकावःगु दु।[२५]अतः, म्युतेसन दर म्युतेसन याइगु तत्त्व व म्युतेसन पनिगु तत्त्वया लिच्वलं निर्धारण याइ।[२८]छुं प्रजाति दसु रेर्तोभाइरसय् यक्व म्युतेसन खनेदु व अन्यागु प्राणीतयेगु यक्व मचातयेके म्युतेतेद जिन दैगु या।[२९]थन्यागु तच्वः गतिया म्युतेसन थ्व प्राणीया निंतिं लाभात्मक जु छाय्धाःसा थ्व प्राणीं त्च्वःगु गतिं विकशित जुया मनुया प्रतिरोधात्मक व्यवस्थाया कारवाहीयात पनेफु व थन्यागु त्च्वःगु म्युतेसन मदूगु जुसा थ्व प्राणी लोप जुइत थाकू मजु।[३०]

म्युतेसन दुप्लिकेसन जुयाच्वंगु दिएनएया तःधंगु खण्डय् जुइफु गुकिलिं विकासक्रमय् न्हुगु जिन उत्पादन यायेत ग्वहालि याइ।[३१]Most genes belong to largerfamilies of genesofshared ancestry.[३२]Novel genes are produced by several methods, commonly through the duplication and mutation of an ancestral gene, or by recombining parts of different genes to form new combinations with new functions.[३३][३४]Here,domainsact as modules, each with a particular and independent function, that can be mixed together to produce genes encoding new proteins with novel properties.[३५]For example, the human eye uses four genes to make structures that sense light: three forcolor visionand one fornight vision;all four arose from a single ancestral gene.[३६]Another advantage of duplicating a gene (or even anentire genome) is that overlapping orredundant functionsin multiple genes allows alleles to be retained that would otherwise be harmful, thus increasing genetic diversity.[३७]

Changes in chromosome number may involve even larger mutations, where segments of the DNA within chromosomes break and then rearrange. For example, two chromosomes in theHomogenusfused to produce humanchromosome 2;this fusion did not occur in thelineageof the other apes, and they retain these separate chromosomes.[३८]In evolution, the most important role of such chromosomal rearrangements may be to accelerate the divergence of a population into new species by making populations less likely to interbreed, and thereby preserving genetic differences between these populations.[३९]

Sequences of DNA that can move about the genome, such astransposons,make up a major fraction of the genetic material of plants and animals, and may have been important in the evolution of genomes.[४०]For example, more than a million copies of theAlu sequenceare present in thehuman genome,and these sequences have now been recruited to perform functions such as regulatinggene expression.[४१]Another effect of these mobile DNA sequences is that when they move within a genome, they can mutate or delete existing genes and thereby produce genetic diversity.[४२]

Sex and recombination[सम्पादन]

In asexual organisms, genes are inherited together, orlinked,as they cannot mix with genes in other organisms during reproduction. However, the offspring ofsexualorganisms contain random mixtures of their parents' chromosomes that are produced throughindependent assortment.In the related process ofgenetic recombination,sexual organisms can also exchange DNA between two matching chromosomes.[४३]Recombination and reassortment do not alter allele frequencies, but instead change which alleles are associated with each other, producing offspring with new combinations of alleles.[४४]While this process increases the variation in any individual's offspring, genetic mi xing can be predicted to either have no effect, increase, or decrease thegenetic variationin the population, depending on how the various alleles in the population are distributed. For example, if two alleles are randomly distributed in a population, then sex will have no effect on variation; however, if two alleles tend to be found as a pair, then genetic mi xing will even out this non-random distribution and over time make the organisms in the population more similar to each other.[४४]The overall effect of sex on natural variation remains unclear, but recent research suggests that sex usually increases genetic variation and may increase the rate of evolution.[४५][४६]

Recombination allows even alleles that are close together in a strand of DNA to beinherited independently.However, the rate of recombination is low, since in humans in a stretch of DNA one millionbase pairslong there is about a one in a hundred chance of a recombination event occurring per generation. As a result, genes close together on a chromosome may not always be shuffled away from each other, and genes that are close together tend to be inherited together.[४७]This tendency is measured by finding how often two alleles of different genes occur together, which is called theirlinkage disequilibrium.A set of alleles that is usually inherited in a group is called ahaplotype.

Sexual reproduction helps to remove harmful mutations and retain beneficial mutations.[४८]Consequently, when alleles cannot be separated by recombination – such as in mammalianY chromosomes,which pass intact from fathers to sons – harmfulmutations accumulate.[४९][५०]In addition, recombination and reassortment can produce individuals with new and advantageous gene combinations. These positive effects are balanced by the fact that this process can cause mutations and separate beneficial combinations of genes.[४८]

Population genetics[सम्पादन]

From a genetic viewpoint, evolution is ageneration-to-generation change in the frequencies of alleles within a population that shares a common gene pool.[५१]Apopulationis a localized group of individuals belonging to the same species. For example, all of the moths of the same species living in an isolated forest represent a population. A single gene in this population may have several alternate forms, which account for variations between the phenotypes of the organisms. An example might be a gene for coloration in moths that has two alleles: black and white. Agene poolis the complete set of alleles in a single population, so each allele occurs a certain number of times in a gene pool. The fraction of genes within the gene pool that are a particular allele is called theallele frequency.Evolution occurs when there are changes in the frequencies of alleles within a population of interbreeding organisms; for example the allele for black color in a population of moths becoming more common.

To understand the mechanisms that cause a population to evolve, it is useful to consider what conditions are required for a population not to evolve. TheHardy-Weinberg principlestates that the frequencies of alleles (variations in a gene) in a sufficiently large population will remain constant if the only forces acting on that population are the random reshuffling of alleles during the formation of the sperm or egg, and the random combination of the alleles in these sex cells duringfertilization.[५२]Such a population is said to be inHardy-Weinberg equilibrium- it is not evolving.[५३]

Mechanisms[सम्पादन]

The three main mechanisms that produce evolution arenatural selection,genetic drift,andgene flow.Natural selection favors genes that improve capacity for survival and reproduction. Genetic drift is random change in the frequency of alleles, caused by the random sampling of a generation's genes during reproduction. Gene flow is the transfer of genes within and between populations. The relative importance of natural selection and genetic drift in a population varies depending on the strength of the selection and theeffective population size,which is the number of individuals capable of breeding.[५४]Natural selection usually predominates in large populations, while genetic drift dominates in small populations. The dominance of genetic drift in small populations can even lead to the fixation of slightly deleterious mutations.[५५]As a result, changing population size can dramatically influence the course of evolution.Population bottlenecks,where the population shrinks temporarily and therefore loses genetic variation, result in a more uniform population.[२१]Bottlenecks also result from alterations in gene flow such as decreased migration,expansions into new habitats,or population subdivision.[५४]

Natural selection[सम्पादन]

Natural selectionis the process by which genetic mutations that enhance reproduction become, and remain, more common in successive generations of a population. It has often been called a "self-evident" mechanism because it necessarily follows from three simple facts:

- Heritable variation exists within populations of organisms.

- Organisms produce more offspring than can survive.

- These offspring vary in their ability to survive and reproduce.

These conditions produce competition between organisms for survival and reproduction. Consequently, organisms with traits that give them an advantage over their competitors pass these advantageous traits on, while traits that do not confer an advantage are not passed on to the next generation.[५६]

The central concept of natural selection is theevolutionary fitnessof an organism. This measures the organism's genetic contribution to the next generation. However, this is not the same as the total number of offspring: instead fitness measures the proportion of subsequent generations that carry an organism's genes.[५७]Consequently, if an allele increases fitness more than the other alleles of that gene, then with each generation this allele will become more common within the population. These traits are said to be "selectedfor".Examples of traits that can increase fitness are enhanced survival, and increasedfecundity.Conversely, the lower fitness caused by having a less beneficial or deleterious allele results in this allele becoming rarer — they are "selectedagainst".[२]Importantly, the fitness of an allele is not a fixed characteristic, if the environment changes, previously neutral or harmful traits may become beneficial and previously beneficial traits become harmful.[१]

Natural selection within a population for a trait that can vary across a range of values, such as height, can be categorized into three different types. The first isdirectional selection,which is a shift in the average value of a trait over time — for example organisms slowly getting taller.[५८]Secondly,disruptive selectionis selection for extreme trait values and often results intwo different valuesbecoming most common, with selection against the average value. This would be when either short or tall organisms had an advantage, but not those of medium height. Finally, instabilizing selectionthere is selection against extreme trait values on both ends, which causes a decrease invariancearound the average value and less diversity.[५९][५६]This would, for example, cause organisms to slowly become all the same height.

A special case of natural selection issexual selection,which is selection for any trait that increases mating success by increasing the attractiveness of an organism to potential mates.[६०]Traits that evolved through sexual selection are particularly prominent in males of some animal species, despite traits such as cumbersome antlers, mating calls or bright colors that attract predators, decreasing the survival of individual males.[६१]This survival disadvantage is balanced by higher reproductive success in males that show thesehard to fake,sexually selected traits.[६२]

Natural selection most generally makes nature the measure against which individuals, and individual traits, are more or less likely to survive. "Nature" in this sense refers to anecosystem,that is, a system in which organisms interact with every other element,physicalas well asbiological,in their localenvironment.Eugene Odum, a founder of ecology, defined an ecosystem as: "Any unit that includes all of the organisms...in a given area interacting with the physical environment so that a flow of energy leads to clearly defined trophic structure, biotic diversity, and material cycles (ie: exchange of materials between living and nonliving parts) within the system."[६३]Each population within an ecosystem occupies a distinctniche,or position, with distinct relationships to other parts of the system. These relationships involve the life history of the organism, its position in thefood chain,and its geographic range. This broad understanding of nature enables scientists to delineate specific forces which, together, comprise natural selection.

An active area of research is theunit of selection,with natural selection being proposed to work at the level of genes, cells, individual organisms, groups of organisms and even species.[६४][६५]None of these are mutually exclusive and selection may act on multiple levels simultaneously.[६६]An example of selection occurring below the level of the individual organism are genes calledtransposons,which can replicate and spread throughout agenome.[६७]Selection at a level above the individual, such asgroup selection,may allow the evolution of co-operation, as discussed below.[६८]

Genetic drift[सम्पादन]

Genetic drift is the change in allele frequency from one generation to the next that occurs because alleles in offspring are arandom sampleof those in the parents, as well as from the role that chance plays in determining whether a given individual will survive and reproduce.[२१]In mathematical terms, alleles are subject tosampling error.As a result, when selective forces are absent or relatively weak, allele frequencies tend to "drift" upward or downward randomly (in arandom walk). This drift halts when an allele eventually becomesfixed,either by disappearing from the population, or replacing the other alleles entirely. Genetic drift may therefore eliminate some alleles from a population due to chance alone. Even in the absence of selective forces, genetic drift can cause two separate populations that began with the same genetic structure to drift apart into two divergent populations with different sets of alleles.[६९]

The time for an allele to become fixed by genetic drift depends on population size, with fixation occurring more rapidly in smaller populations.[७०]The precise measure of population that is important is called theeffective population size.The effective population is always smaller than the total population since it takes into account factors such as the level of inbreeding, the number of animals that are too old or young to breed, and the lower probability of animals that live far apart managing to mate with each other.[७१]

Although natural selection is responsible for adaptation, the relative importance of the two forces of natural selection and genetic drift in driving evolutionary change in general is an area of current research in evolutionary biology.[७२]These investigations were prompted by theneutral theory of molecular evolution,which proposed that most evolutionary changes are the result of the fixation ofneutral mutationsthat do not have any immediate effects on the fitness of an organism.[७३]Hence, in this model, most genetic changes in a population are the result of constant mutation pressure and genetic drift.[७४]This form of the neutral theory is now largely abandoned, since it does not seem to fit the genetic variation seen in nature.[७५][७६]However, a more recent and better-supported version of this model is thenearly-neutral theory,where most mutations only have small effects on fitness.[५६]

Gene flow[सम्पादन]

Gene flowis the exchange of genes between populations, which are usually of the same species.[७७]Examples of gene flow within a species include the migration and then breeding of organisms, or the exchange ofpollen.Gene transfer between species includes the formation ofhybridorganisms andhorizontal gene transfer.

Migration into or out of a population can change allele frequencies, as well as introducing genetic variation into a population. Immigration may add new genetic material to the establishedgene poolof a population. Conversely, emigration may remove genetic material. Asbarriers to reproductionbetween two diverging populations are required for the populations tobecome new species,gene flow may slow this process by spreading genetic differences between the populations. Gene flow is hindered by mountain ranges, oceans and deserts or even man-made structures such as theGreat Wall of China,which has hindered the flow of plant genes.[७८]

Depending on how far two species have diverged since theirmost recent common ancestor,it may still be possible for them to produce offspring, as withhorsesanddonkeysmating to producemules.[७९]Suchhybridsare generallyinfertile,due to the two different sets of chromosomes being unable to pair up duringmeiosis.In this case, closely related species may regularly interbreed, but hybrids will be selected against and the species will remain distinct. However, viable hybrids are occasionally formed and these new species can either have properties intermediate between their parent species, or possess a totally new phenotype.[८०]The importance of hybridization in creatingnew speciesof animals is unclear, although cases have been seen in many types of animals,[८१]with thegray tree frogbeing a particularly well-studied example.[८२]

Hybridization is, however, an important means of speciation in plants, sincepolyploidy(having more than two copies of each chromosome) is tolerated in plants more readily than in animals.[८३][८४]Polyploidy is important in hybrids as it allows reproduction, with the two different sets of chromosomes each being able to pair with an identical partner during meiosis.[८५]Polyploids also have more genetic diversity, which allows them to avoidinbreeding depressionin small populations.[८६]

Horizontal gene transferis the transfer of genetic material from one organism to another organism that is not its offspring; this is most common amongbacteria.[८७]In medicine, this contributes to the spread ofantibiotic resistance,as when one bacteria acquires resistance genes it can rapidly transfer them to other species.[८८]Horizontal transfer of genes from bacteria to eukaryotes such as the yeastSaccharomyces cerevisiaeand the adzuki bean beetleCallosobruchus chinensismay also have occurred.[८९][९०]An example of larger-scale transfers are the eukaryoticbdelloid rotifers,which appear to have received a range of genes from bacteria, fungi, and plants.[९१]Virusescan also carry DNA between organisms, allowing transfer of genes even acrossbiological domains.[९२]Large-scale gene transfer has also occurred between the ancestors ofeukaryotic cellsand prokaryotes, during the acquisition ofchloroplastsandmitochondria.[९३]

Outcomes[सम्पादन]

Evolution influences every aspect of the form and behavior of organisms. Most prominent are the specific behavioral and physicaladaptationsthat are the outcome of natural selection. These adaptations increase fitness by aiding activities such as finding food, avoiding predators or attracting mates. Organisms can also respond to selection byco-operatingwith each other, usually by aiding their relatives or engaging in mutually beneficialsymbiosis.In the longer term, evolution produces new species through splitting ancestral populations of organisms into new groups that cannot or will not interbreed.

These outcomes of evolution are sometimes divided intomacroevolution,which is evolution that occurs at or above the level of species, such asextinctionandspeciation,andmicroevolution,which is smaller evolutionary changes, such as adaptations, within a species or population. In general, macroevolution is regarded as the outcome of long periods of microevolution.[९४]Thus, the distinction between micro- and macroevolution is not a fundamental one - the difference is simply the time involved.[९५]However, in macroevolution, the traits of the entire species may be important. For instance, a large amount of variation among individuals allows a species to rapidly adapt to new habitats, lessening the chance of it going extinct, while a wide geographic range increases the chance of speciation, by making it more likely that part of the population will become isolated. In this sense, microevolution and macroevolution might involve selection at different levels - with microevolution acting on genes and organisms, versus macroevolutionary processes acting on entire species and affecting the rate of speciation and extinction.[९६][९७][९८]

A common misconception is that evolution is "progressive," but natural selection has no long-term goal and does not necessarily produce greater complexity.[९९][१००]Althoughcomplex specieshave evolved, this occurs as a side effect of the overall number of organisms increasing, and simple forms of life remain more common.[१०१]For example, the overwhelming majority of species are microscopicprokaryotes,which form about half the world'sbiomassdespite their small size,[१०२]and constitute the vast majority of Earth's biodiversity.[१०३]Simple organisms have therefore been the dominant form of life on Earth throughout its history and continue to be the main form of life up to the present day, with complex life only appearing more diverse because it ismore noticeable.[१०४]

Adaptation[सम्पादन]

Adaptations are structures or behaviors that enhance a specific function, causing organisms to become better at surviving and reproducing.[७]They are produced by a combination of the continuous production of small, random changes in traits, followed by natural selection of the variants best-suited for their environment.[१०५]This process can cause either the gain of a new feature, or the loss of an ancestral feature. An example that shows both types of change is bacterial adaptation toantibioticselection, with genetic changes causingantibiotic resistanceby both modifying the target of the drug, or increasing the activity of transporters that pump the drug out of the cell.[१०६]Other striking examples are the bacteriaEscherichia colievolving the ability to usecitric acidas a nutrient in along-term laboratory experiment,[१०७]Flavobacteriumevolving a novel enzyme that allows these bacteria to grow on the by-products ofnylonmanufacturing,[१०८][१०९]and the soil bacteriumSphingobiumevolving an entirely newmetabolic pathwaythat degrades the syntheticpesticidepentachlorophenol.[११०][१११]

However, many traits that appear to be simple adaptations are in factexaptations:structures originally adapted for one function, but which coincidentally became somewhat useful for some other function in the process.[११२]One example is the African lizardHolaspis guentheri,which developed an extremely flat head for hiding in crevices, as can be seen by looking at its near relatives. However, in this species, the head has become so flattened that it assists in gliding from tree to tree—anexaptation.[११२]Another is the recruitment of enzymes fromglycolysisandxenobiotic metabolismto serve as structural proteins calledcrystallinswithin the lenses of organisms'eyes.[११३][११४]

As adaptation occurs through the gradual modification of existing structures, structures with similar internal organization may have very different functions in related organisms. This is the result of a singleancestral structurebeing adapted to function in different ways. The bones within bat wings, for example, are structurally similar to both human hands and seal flippers, due to the common descent of these structures from an ancestor that also had five digits at the end of each forelimb. Other idiosyncratic anatomical features, such asbones in the wristof thepandabeing formed into a false "thumb," indicate that an organism's evolutionary lineage can limit what adaptations are possible.[११६]

During adaptation, some structures may lose their original function and becomevestigial structures.[११७]Such structures may have little or no function in a current species, yet have a clear function in ancestral species, or other closely related species. Examples includepseudogenes,[११८]the non-functional remains of eyes in blind cave-dwelling fish,[११९]wings in flightless birds,[१२०]and the presence of hip bones in whales and snakes.[१२१]Examples of vestigial structures in humans includewisdom teeth,[१२२]thecoccyx,[११७]and thevermiform appendix.[११७]

A critical principle ofecologyis that ofcompetitive exclusion:no two species can occupy the same niche in the same environment for a long time.[१२३]Consequently, natural selection will tend to force species to adapt to differentecological niches.This may mean that, for example, two species ofcichlidfish adapt to live in differenthabitats,which will minimize the competition between them for food.[१२४]

An area of current investigation inevolutionary developmental biologyis thedevelopmentalbasis of adaptations and exaptations.[१२५]This research addresses the origin and evolution ofembryonic developmentand how modifications of development and developmental processes produce novel features.[१२६]These studies have shown that evolution can alter development to create new structures, such as embryonic bone structures that develop into the jaw in other animals instead forming part of the middle ear in mammals.[१२७]It is also possible for structures that have been lost in evolution to reappear due to changes in developmental genes, such as a mutation inchickenscausing embryos to grow teeth similar to those ofcrocodiles.[१२८]It is now becoming clear that most alterations in the form of organisms are due to changes in the level and timing of the expression of a small set of conserved genes.[१२९]

Co-evolution[सम्पादन]

Interactions between organisms can produce both conflict and co-operation. When the interaction is between pairs of species, such as apathogenand ahost,or apredatorand its prey, these species can develop matched sets of adaptations. Here, the evolution of one species causes adaptations in a second species. These changes in the second species then, in turn, cause new adaptations in the first species. This cycle of selection and response is calledco-evolution.[१३०]An example is the production oftetrodotoxinin therough-skinned newtand the evolution of tetrodotoxin resistance in its predator, thecommon garter snake.In this predator-prey pair, anevolutionary arms racehas produced high levels of toxin in the newt and correspondingly high levels of resistance in the snake.[१३१]

Co-operation[सम्पादन]

However, not all interactions between species involve conflict.[१३२]Many cases of mutually beneficial interactions have evolved. For instance, an extreme cooperation exists between plants and themycorrhizal fungithat grow on their roots and aid the plant in absorbing nutrients from the soil.[१३३]This is areciprocalrelationship as the plants provide the fungi with sugars from photosynthesis. Here, the fungi actually grow inside plant cells, allowing them to exchange nutrients with their hosts, while sendingsignalsthat suppress the plantimmune system.[१३४]

Coalitions between organisms of the same species have also evolved. An extreme case is theeusocialityfound insocial insects,such asbees,termitesandants,where sterile insects feed and guard the small number of organisms in acolonythat are able to reproduce. On an even smaller scale, thesomatic cellsthat make up the body of an animal limit their reproduction so they can maintain a stable organism, which then supports a small number of the animal'sgerm cellsto produce offspring. Here, somatic cells respond to specific signals that instruct them whether to grow, remain as they are, or die. If cells ignore these signals and multiply inappropriately, their uncontrolled growthcauses cancer.[२५]

These examples of cooperation within species are thought to have evolved through the process ofkin selection,which is where one organism acts to help raise a relative's offspring.[१३५]This activity is selected for because if thehelpingindividual contains alleles which promote the helping activity, it is likely that its kin willalsocontain these alleles and thus those alleles will be passed on.[१३६]Other processes that may promote cooperation includegroup selection,where cooperation provides benefits to a group of organisms.[१३७]

Speciation[सम्पादन]

Speciationis the process where a species diverges into two or more descendant species.[१३८]Evolutionary biologists view species as statistical phenomena and not categories or types. This view is counterintuitive since the classical idea of species is still widely-held, with a species seen as a class of organisms exemplified by a "type specimen"that bears all the traits common to this species. Instead, a species is now defined as a separately evolving lineage that forms a singlegene pool.Although properties such as genetics and morphology are used to help separate closely-related lineages, this definition has fuzzy boundaries.[१३९]However, the exact definition of the term "species" is still controversial, particularly in prokaryotes,[१४०]and this is called thespecies problem.[१४१]Biologists have proposed a range of more precise definitions, but the definition used is a pragmatic choice that depends on the particularities of the species concerned.[१४१]Typically the actual focus on biological study is thepopulation,an observableinteractinggroup of organisms, rather than aspecies,an observablesimilargroup of individuals.

Speciation has been observed multiple times under both controlled laboratory conditions and in nature.[१४२]In sexually reproducing organisms, speciation results from reproductive isolation followed by genealogical divergence. There are four mechanisms for speciation. The most common in animals isallopatric speciation,which occurs in populations initially isolated geographically, such as byhabitat fragmentationor migration. Selection under these conditions can produce very rapid changes in the appearance and behaviour of organisms.[१४३][१४४]As selection and drift act independently on populations isolated from the rest of their species, separation may eventually produce organisms that cannot interbreed.[१४५]

The second mechanism of speciation isperipatric speciation,which occurs when small populations of organisms become isolated in a new environment. This differs from allopatric speciation in that the isolated populations are numerically much smaller than the parental population. Here, thefounder effectcauses rapid speciation through both rapid genetic drift and selection on a small gene pool.[१४६]

The third mechanism of speciation isparapatric speciation.This is similar to peripatric speciation in that a small population enters a new habitat, but differs in that there is no physical separation between these two populations. Instead, speciation results from the evolution of mechanisms that reduce gene flow between the two populations.[१३८]Generally this occurs when there has been a drastic change in the environment within the parental species' habitat. One example is the grassAnthoxanthum odoratum,which can undergo parapatric speciation in response to localized metal pollution from mines.[१४७]Here, plants evolve that have resistance to high levels of metals in the soil. Selection against interbreeding with the metal-sensitive parental population produces a change in flowering time of the metal-resistant plants, causing reproductive isolation. Selection against hybrids between the two populations may causereinforcement,which is the evolution of traits that promote mating within a species, as well ascharacter displacement,which is when two species become more distinct in appearance.[१४८]

Finally, insympatric speciationspecies diverge without geographic isolation or changes in habitat. This form is rare since even a small amount ofgene flowmay remove genetic differences between parts of a population.[१४९]Generally, sympatric speciation in animals requires the evolution of bothgenetic differencesandnon-random mating,to allow reproductive isolation to evolve.[१५०]

One type of sympatric speciation involves cross-breeding of two related species to produce a newhybridspecies. This is not common in animals as animal hybrids are usually sterile. This is because duringmeiosisthehomologous chromosomesfrom each parent are from different species and cannot successfully pair. However, it is more common in plants because plants often double their number of chromosomes, to formpolyploids.This allows the chromosomes from each parental species to form a matching pair during meiosis, since as each parent's chromosomes is represented by a pair already.[१५१]An example of such a speciation event is when the plant speciesArabidopsis thalianaandArabidopsis arenosacross-bred to give the new speciesArabidopsis suecica.[१५२]This happened about 20,000 years ago,[१५३]and the speciation process has been repeated in the laboratory, which allows the study of the genetic mechanisms involved in this process.[१५४]Indeed, chromosome doubling within a species may be a common cause of reproductive isolation, as half the doubled chromosomes will be unmatched when breeding with undoubled organisms.[८४]

Speciation events are important in the theory ofpunctuated equilibrium,which accounts for the pattern in the fossil record of short "bursts" of evolution interspersed with relatively long periods of stasis, where species remain relatively unchanged.[१५५]In this theory, speciation and rapid evolution are linked, with natural selection and genetic drift acting most strongly on organisms undergoing speciation in novel habitats or small populations. As a result, the periods of stasis in the fossil record correspond to the parental population, and the organisms undergoing speciation and rapid evolution are found in small populations or geographically restricted habitats, and therefore rarely being preserved as fossils.[१५६]

Extinction[सम्पादन]

Extinctionis the disappearance of an entire species. Extinction is not an unusual event, as species regularly appear through speciation, and disappear through extinction.[१५७]Indeed, virtually all animal and plant species that have lived on earth are now extinct,[१५८]and extinction appears to be the ultimate fate of all species.[१५९]These extinctions have happened continuously throughout the history of life, although the rate of extinction spikes in occasional massextinction events.[१६०]TheCretaceous–Tertiary extinction event,during which the dinosaurs went extinct, is the most well-known, but the earlierPermian–Triassic extinction eventwas even more severe, with approximately 96 percent of species driven to extinction.[१६०]TheHolocene extinction eventis an ongoing mass extinction associated with humanity's expansion across the globe over the past few thousand years. Present-day extinction rates are 100-1000 times greater than the background rate, and up to 30 percent of species may be extinct by the mid 21st century.[१६१]Human activities are now the primary cause of the ongoing extinction event;[१६२]global warmingmay further accelerate it in the future.[१६३]

The role of extinction in evolution depends on which type is considered. The causes of the continuous "low-level" extinction events, which form the majority of extinctions, are not well understood and may be the result of competition between species for limited resources (competitive exclusion).[१२]If competition from other species does alter the probability that a species will become extinct, this could producespecies selectionas a level of natural selection.[६४]The intermittent mass extinctions are also important, but instead of acting as a selective force, they drastically reduce diversity in a nonspecific manner and promote bursts ofrapid evolutionand speciation in survivors.[१६०]

Evolutionary history of life[सम्पादन]

Origin of life[सम्पादन]

The origin oflifeis a necessary precursor for biological evolution, but understanding that evolution occurred once organisms appeared and investigating how this happens does not depend on understanding exactly how life began.[१६४]The currentscientific consensusis that the complexbiochemistrythat makes up life came from simpler chemical reactions, but it is unclear how this occurred.[१६५]Not much is certain about the earliest developments in life, the structure of the first living things, or the identity and nature of anylast universal common ancestoror ancestral gene pool.[१६६][१६७]Consequently, there is no scientific consensus on how life began, but proposals include self-replicating molecules such asRNA,[१६८]and the assembly of simple cells.[१६९]

Common descent[सम्पादन]

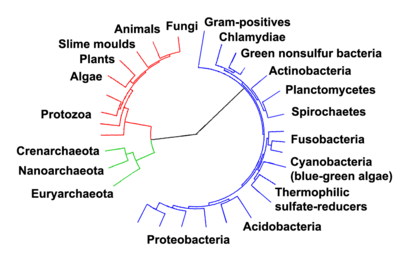

AllorganismsonEarthare descended from a common ancestor or ancestral gene pool.[१७०]Current species are a stage in the process of evolution, with their diversity the product of a long series of speciation and extinction events.[१७१]Thecommon descentof organisms was first deduced from four simple facts about organisms: First, they have geographic distributions that cannot be explained by local adaptation. Second, the diversity of life is not a set of completely unique organisms, but organisms that share morphological similarities. Third, vestigial traits with no clear purpose resemble functional ancestral traits, and finally, that organisms can be classified using these similarities into a hierarchy of nested groups - similar to a family tree.[७]However, modern research has suggested that, due to horizontal gene transfer, this "tree of life"may be more complicated than a simple branching tree since some genes have spread independently between distantly-related species.[१७२][१७३]

Past species have also left records of their evolutionary history.Fossils,along with the comparative anatomy of present-day organisms, constitute the morphological, or anatomical, record.[१७४]By comparing the anatomies of both modern and extinct species, paleontologists can infer the lineages of those species. However, this approach is most successful for organisms that had hard body parts, such as shells, bones or teeth. Further, as prokaryotes such asbacteriaandarchaeashare a limited set of common morphologies, their fossils do not provide information on their ancestry.

More recently, evidence for common descent has come from the study ofbiochemicalsimilarities between organisms. For example, all living cells use the same basic set ofnucleotidesandamino acids.[१७५]The development ofmolecular geneticshas revealed the record of evolution left in organisms'genomes:dating when species diverged through themolecular clockproduced by mutations.[१७६]For example, these DNA sequence comparisons have revealed the close genetic similarity between humans and chimpanzees and shed light on when the common ancestor of these species existed.[१७७]

Evolution of life[सम्पादन]

Despite the uncertainty on how life began, it is generally accepted thatprokaryotesinhabited the Earth from approximately 3–4 billion years ago.[१७९][१८०]No obvious changes inmorphologyor cellular organization occurred in these organisms over the next few billion years.[१८१]

Theeukaryoteswere the next major change in cell structure. These came from ancient bacteria being engulfed by the ancestors of eukaryotic cells, in a cooperative association calledendosymbiosis.[९३][१८२]The engulfed bacteria and the host cell then underwent co-evolution, with the bacteria evolving into eithermitochondriaorhydrogenosomes.[१८३]An independent second engulfment ofcyanobacterial-like organisms led to the formation ofchloroplastsin algae and plants.[१८४]It is unknown when the first eukaryotic cells appeared though they first emerged between 1.6 - 2.7 billion years ago.

The history of life was that of the unicellular eukaryotes, prokaryotes, and archaea until about 610 million years ago when multicellular organisms began to appear in the oceans in theEdiacaranperiod.[१७९][१८५]Theevolution of multicellularityoccurred in multiple independent events, in organisms as diverse assponges,brown algae,cyanobacteria,slime mouldsandmyxobacteria.[१८६]

Soon after the emergence of these first multicellular organisms, a remarkable amount of biological diversity appeared over approximately 10 million years, in an event called theCambrian explosion.Here, the majority oftypesof modern animals appeared in the fossil record, as well as unique lineages that subsequently became extinct.[१८७]Various triggers for the Cambrian explosion have been proposed, including the accumulation ofoxygenin theatmospherefromphotosynthesis.[१८८]About 500 million years ago,plantsandfungicolonized the land, and were soon followed byarthropodsand other animals.[१८९]Amphibiansfirst appeared around 300 million years ago, followed by earlyamniotes,thenmammalsaround 200 million years ago andbirdsaround 100 million years ago (both from "reptile"-like lineages). However, despite the evolution of these large animals, smaller organisms similar to the types that evolved early in this process continue to be highly successful and dominate the Earth, with the majority of bothbiomassand species being prokaryotes.[१०३]

History of evolutionary thought[सम्पादन]

Evolutionary ideas such ascommon descentand thetransmutation of specieshave existed since at least the 6th century BC, when they were expounded by theGreek philosopherAnaximander.[१९०]Others who considered such ideas included the Greek philosopherEmpedocles,theRoman philosopher-poetLucretius,theArab biologistAl-Jahiz,[१९१]thePersian philosopherIbn Miskawayh,theBrethren of Purity,[१९२]and the Chinese philosopherZhuangzi.[१९३]As biological knowledge grew in the 18th century, evolutionary ideas were set out by a few natural philosophers includingPierre Maupertuisin 1745 andErasmus Darwinin 1796.[१९४]The ideas of the biologistJean-Baptiste Lamarckabouttransmutation of specieshad wide influence.Charles Darwinformulated his idea ofnatural selectionin 1838 and was still developing his theory in 1858 whenAlfred Russel Wallacesent him a similar theory, and both were presented to theLinnean Society of Londoninseparate papers.[१९५]At the end of 1859 Darwin's publication ofOn the Origin of Speciesexplained natural selection in detail and presented evidence leading to increasingly wide acceptance of the occurrence of evolution.

Debate about the mechanisms of evolution continued, and Darwin could not explain the source of the heritable variations which would be acted on by natural selection. Like Lamarck, he thought that parentspassed on adaptations acquiredduring their lifetimes,[१९६]a theory which was subsequently dubbedLamarckism.[१९७]In the 1880sAugust Weismann'sexperiments indicated that changes from use and disuse were not heritable, and Lamarckism gradually fell from favour.[१९८][१९९]More significantly, Darwin could not account for how traits were passed down from generation to generation. In 1865Gregor Mendelfound that traits wereinheritedin a predictable manner.[२००]When Mendel's work was rediscovered in 1900s, disagreements over the rate of evolution predicted by early geneticists andbiometriciansled to a rift between the Mendelian and Darwinian models of evolution.

Yet it was the rediscovery of Gregor Mendel’s pioneering work on the fundamentals of genetics (of which Darwin and Wallace were unaware) byHugo de Vriesand others in the early 1900s that provided the impetus for a better understanding of how variation occurs in plant and animal traits. That variation is the main fuel used by natural selection to shape the wide variety of adaptive traits observed in organic life. Even thoughHugo de Vriesand other early geneticists were very critical of the theory of evolution, their rediscovery of and subsequent work on genetics eventually provided a solid basis on which the theory of evolution stood even more convincingly than when it was originally proposed.[२०१]

The apparent contradiction between Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection and Mendel’s work was reconciled in the 1920s and 1930s by evolutionary biologists such asJ.B.S. Haldane,Sewall Wright,and particularlyRonald Fisher,who set the foundations for the establishment of the field ofpopulation genetics.The end result was a combination of evolution by natural selection and Mendelian inheritance, themodern evolutionary synthesis.[२०२]In the 1940s, the identification ofDNAas the genetic material byOswald Averyand colleagues and the subsequent publication of the structure of DNA byJames WatsonandFrancis Crickin 1953, demonstrated the physical basis for inheritance. Since then,geneticsandmolecular biologyhave become core parts ofevolutionary biologyand have revolutionized the field ofphylogenetics.[१२]

In its early history, evolutionary biology primarily drew in scientists from traditional taxonomically oriented disciplines, whose specialist training in particular organisms addressed general questions in evolution. As evolutionary biology expanded as an academic discipline, particularly after the development of the modern evolutionary synthesis, it began to draw more widely from the biological sciences.[१२]Currently the study of evolutionary biology involves scientists from fields as diverse asbiochemistry,ecology,geneticsandphysiology,and evolutionary concepts are used in even more distant disciplines such aspsychology,medicine,philosophyandcomputer science.

Social and cultural responses[सम्पादन]

In the 19th century, particularly after the publication ofOn the Origin of Species,the idea that life had evolved was an active source of academic debate centered on the philosophical, social and religious implications of evolution. Nowadays, the fact that organisms evolve is uncontested in thescientific literatureand the modern evolutionary synthesis is widely accepted by scientists. However, evolution remains a contentious concept for some religious groups.[२०४]

Whilemany religions and denominationshave reconciled their beliefs with evolution through various concepts oftheistic evolution,there are manycreationistswho believe that evolution is contradicted by thecreation mythsfound in their respective religions.[२०५]As Darwin recognized early on, the most controversial aspect of evolutionary biology is its implications forhuman origins.In some countries—notably the United States—these tensions between science and religion have fueled the ongoingcreation–evolution controversy,a religious conflict focusing onpoliticsandpublic education.[२०६]While other scientific fields such ascosmology[२०७]andearth science[२०८]also conflict with literal interpretations of many religious texts, evolutionary biology experiences significantly more opposition from religious literalists.

Another example associated with evolutionary theory that is now widely regarded as unwarranted is misnamed "Social Darwinism,"a term given to the 19th centuryWhigMalthusiantheory developed byHerbert Spencerinto ideas about "survival of the fittest"in commerce and human societies as a whole, and by others into claims thatsocial inequality,racism, andimperialismwere justified.[२०९]However, these ideas contradictDarwin's own views, and contemporary scientists and philosophers consider these ideas to be neither mandated by evolutionary theory nor supported by data.[२१०][२११]

Applications[सम्पादन]

A major technological application of evolution isartificial selection,which is the intentional selection of certain traits in a population of organisms. Humans have used artificial selection for thousands of years in thedomesticationof plants and animals.[२१२]More recently, such selection has become a vital part ofgenetic engineering,withselectable markerssuch as antibiotic resistance genes being used to manipulate DNA inmolecular biology.

As evolution can produce highly optimized processes and networks, it has many applications incomputer science.Here, simulations of evolution usingevolutionary algorithmsandartificial lifestarted with the work of Nils Aall Barricelli in the 1960s, and was extended byAlex Fraser,who published a series of papers on simulation ofartificial selection.[२१३]Artificial evolutionbecame a widely recognized optimization method as a result of the work ofIngo Rechenbergin the 1960s and early 1970s, who usedevolution strategiesto solve complex engineering problems.[२१४]Genetic algorithmsin particular became popular through the writing ofJohn Holland.[२१५]As academic interest grew, dramatic increases in the power of computers allowed practical applications, including the automatic evolution of computer programs.[२१६]Evolutionary algorithms are now used to solve multi-dimensional problems more efficiently than software produced by human designers, and also to optimize the design of systems.[२१७]

लिधंसा[सम्पादन]

- ↑१.०१.११.२Futuyma, Douglas J.(2005).Evolution.Sunderland, Massachusetts: Sinauer Associates, Inc.

- ↑२.०२.१Lande R, Arnold SJ (1983). "The measurement of selection on correlated characters".Evolution37:1210–26}.DOI:10.2307/2408842.

- ↑Ayala FJ (2007). "Darwin's greatest discovery: design without designer".Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.104 Suppl 1:8567–73.DOI:10.1073/pnas.0701072104.PMID 17494753.

- ↑(Gould 2002)

- ↑Ian C. Johnston (1999).History of Science: Early Modern Geology.Malaspina University-College.2008-01-15 कथं।

- ↑Bowler, Peter J.(2003).Evolution:The History of an Idea.University of California Press.

- ↑७.०७.१७.२Darwin, Charles(1859).On the Origin of Species,1st, John Murray, 1..Related earlier ideas were acknowledged inDarwin, Charles(1861).On the Origin of Species,3rd, John Murray, xiii.

- ↑AAAS Council (December 26, 1922).AAAS Resolution: Present Scientific Status of the Theory of Evolution.American Association for the Advancement of Science.

- ↑९.०९.१IAP Statement on the Teaching of Evolution(PDF). The Interacademy Panel on International Issues (2006). 2007-04-25 कथं। बेलायतया रोयल सोसाइटीनापं हलिमया ६७गु देय्या राष्ट्रिय वैज्ञानिक एकेदमिं पिथंगु संयुक्त वक्तव्य।

- ↑१०.०१०.१Board of Directors, American Association for the Advancement of Science (2006-02-16).Statement on the Teaching of Evolution(PDF). American Association for the Advancement of Science. from the world's largest general scientific society

- ↑Statements from Scientific and Scholarly Organizations.National Center for Science Education.

- ↑१२.०१२.११२.२१२.३Kutschera U, Niklas K (2004). "The modern theory of biological evolution: an expanded synthesis".Naturwissenschaften91(6): 255–76.DOI:10.1007/s00114-004-0515-y.PMID 15241603.

- ↑Special report on evolution.New Scientist (2008-01-19).

- ↑Sturm RA, Frudakis TN (2004). "Eye colour: portals into pigmentation genes and ancestry".Trends Genet.20(8): 327–32.DOI:10.1016/j.tig.2004.06.010.PMID 15262401.

- ↑१५.०१५.१Pearson H (2006). "Genetics: what is a gene?".Nature441(7092): 398–401.DOI:10.1038/441398a.PMID 16724031.

- ↑Visscher PM, Hill WG, Wray NR (April 2008). "Heritability in the genomics era--concepts and misconceptions".Nat. Rev. Genet.9(4): 255–66.DOI:10.1038/nrg2322.PMID 18319743.

- ↑Oetting WS, Brilliant MH, King RA (1996). "The clinical spectrum of albinism in humans".Molecular medicine today2(8): 330–35.DOI:10.1016/1357-4310(96)81798-9.PMID 8796918.

- ↑Phillips PC (November 2008). "Epistasis--the essential role of gene interactions in the structure and evolution of genetic systems".Nat. Rev. Genet.9(11): 855–67.DOI:10.1038/nrg2452.PMID 18852697.

- ↑१९.०१९.१Wu R, Lin M (2006). "Functional mapping - how to map and study the genetic architecture of dynamic complex traits".Nat. Rev. Genet.7(3): 229–37.DOI:10.1038/nrg1804.PMID 16485021.

- ↑Richards EJ (May 2006). "Inherited epigenetic variation--revisiting soft inheritance".Nat. Rev. Genet.7(5): 395–401.DOI:10.1038/nrg1834.PMID 16534512.

- ↑२१.०२१.१२१.२Harwood AJ (1998). "Factors affecting levels of genetic diversity in natural populations".Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond., B, Biol. Sci.353(1366): 177–86.DOI:10.1098/rstb.1998.0200.PMID 9533122.

- ↑Draghi J, Turner P (2006). "DNA secretion and gene-level selection in bacteria".Microbiology (Reading, Engl.)152(Pt 9): 2683–8.PMID 16946263.

*Mallet J (2007). "Hybrid speciation".Nature446(7133): 279–83.DOI:10.1038/nature05706.PMID 17361174. - ↑Butlin RK, Tregenza T (1998). "Levels of genetic polymorphism: marker loci versus quantitative traits".Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond., B, Biol. Sci.353(1366): 187–98.DOI:10.1098/rstb.1998.0201.PMID 9533123.

- ↑Wetterbom A, Sevov M, Cavelier L, Bergström TF (2006). "Comparative genomic analysis of human and chimpanzee indicates a key role for indels in primate evolution".J. Mol. Evol.63(5): 682–90.DOI:10.1007/s00239-006-0045-7.PMID 17075697.

- ↑२५.०२५.१२५.२Bertram J (2000). "The molecular biology of cancer".Mol. Aspects Med.21(6): 167–223.DOI:10.1016/S0098-2997(00)00007-8.PMID 11173079.

- ↑Aminetzach YT, Macpherson JM, Petrov DA (2005). "Pesticide resistance via transposition-mediated adaptive gene truncation in Drosophila".Science309(5735): 764–67.DOI:10.1126/science.1112699.PMID 16051794.

- ↑Burrus V, Waldor M (2004). "Shaping bacterial genomes with integrative and conjugative elements".Res. Microbiol.155(5): 376–86.DOI:10.1016/j.resmic.2004.01.012.PMID 15207870.

- ↑Sniegowski P, Gerrish P, Johnson T, Shaver A (2000). "The evolution of mutation rates: separating causes from consequences".Bioessays22(12): 1057–66.DOI:<1057::AID-BIES3>3.0.CO;2-W 10.1002/1521-1878(200012)22:12<1057::AID-BIES3>3.0.CO;2-W.PMID 11084621.

- ↑Drake JW, Charlesworth B, Charlesworth D, Crow JF (1998). "Rates of spontaneous mutation".Genetics148(4): 1667–86.PMID 9560386.

- ↑Holland J, Spindler K, Horodyski F, Grabau E, Nichol S, VandePol S (1982). "Rapid evolution of RNA genomes".Science215(4540): 1577–85.DOI:10.1126/science.7041255.PMID 7041255.

- ↑Carroll SB, Grenier J, Weatherbee SD (2005).From DNA to Diversity: Molecular Genetics and the Evolution of Animal Design. Second Edition.Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

- ↑Harrison P, Gerstein M (2002). "Studying genomes through the aeons: protein families, pseudogenes and proteome evolution".J Mol Biol318(5): 1155–74.DOI:10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00109-2.PMID 12083509.

- ↑Orengo CA, Thornton JM (2005). "Protein families and their evolution-a structural perspective".Annu. Rev. Biochem.74:867–900.DOI:10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.082803.133029.PMID 15954844.

- ↑Long M, Betrán E, Thornton K, Wang W (November 2003). "The origin of new genes: glimpses from the young and old".Nat. Rev. Genet.4(11): 865–75.DOI:10.1038/nrg1204.PMID 14634634.

- ↑Wang M, Caetano-Anollés G (2009). "The evolutionary mechanics of domain organization in proteomes and the rise of modularity in the protein world".Structure17(1): 66–78.DOI:doi:10.1016/j.str.2008.11.008.

- ↑Bowmaker JK (1998). "Evolution of colour vision in vertebrates".Eye (London, England)12 (Pt 3b):541–47.PMID 9775215.

- ↑Gregory TR, Hebert PD (1999). "The modulation of DNA content: proximate causes and ultimate consequences".Genome Res.9(4): 317–24.PMID 10207154.

- ↑Zhang J, Wang X, Podlaha O (2004). "Testing the chromosomal speciation hypothesis for humans and chimpanzees".Genome Res.14(5): 845–51.DOI:10.1101/gr.1891104.PMID 15123584.

- ↑Ayala FJ, Coluzzi M (2005). "Chromosome speciation: humans, Drosophila, and mosquitoes".Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.102 Supplement 1:6535–42.DOI:10.1073/pnas.0501847102.PMID 15851677.

- ↑Hurst GD, Werren JH (2001). "The role of selfish genetic elements in eukaryotic evolution".Nat. Rev. Genet.2(8): 597–606.DOI:10.1038/35084545.PMID 11483984.

- ↑Häsler J, Strub K (2006). "Alu elements as regulators of gene expression".Nucleic Acids Res.34(19): 5491–97.DOI:10.1093/nar/gkl706.PMID 17020921.

- ↑Aminetzach YT, Macpherson JM, Petrov DA (2005). "Pesticide resistance via transposition-mediated adaptive gene truncation in Drosophila".Science309(5735): 764–67.DOI:10.1126/science.1112699.PMID 16051794.

- ↑Radding C (1982). "Homologous pairing and strand exchange in genetic recombination".Annu. Rev. Genet.16:405–37.DOI:10.1146/annurev.ge.16.120182.002201.PMID 6297377.

- ↑४४.०४४.१Agrawal AF (2006). "Evolution of sex: why do organisms shuffle their genotypes?".Curr. Biol.16(17): R696.DOI:10.1016/j.cub.2006.07.063.PMID 16950096.

- ↑Peters AD, Otto SP (2003). "Liberating genetic variance through sex".Bioessays25(6): 533–7.DOI:10.1002/bies.10291.PMID 12766942.

- ↑Goddard MR, Godfray HC, Burt A (2005). "Sex increases the efficacy of natural selection in experimental yeast populations".Nature434(7033): 636–40.DOI:10.1038/nature03405.PMID 15800622.

- ↑Lien S, Szyda J, Schechinger B, Rappold G, Arnheim N (2000). "Evidence for heterogeneity in recombination in the human pseudoautosomal region: high resolution analysis by sperm typing and radiation-hybrid mapping".Am. J. Hum. Genet.66(2): 557–66.DOI:10.1086/302754.PMID 10677316.

- ↑४८.०४८.१Otto S (2003). "The advantages of segregation and the evolution of sex".Genetics164(3): 1099–118.PMID 12871918.

- ↑Muller H (1964). "The relation of recombination to mutational advance".Mutat. Res.106:2–9.PMID 14195748.

- ↑Charlesworth B, Charlesworth D (2000). "The degeneration of Y chromosomes".Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond., B, Biol. Sci.355(1403): 1563–72.DOI:10.1098/rstb.2000.0717.PMID 11127901.

- ↑Stoltzfus A (2006). "Mutationism and the dual causation of evolutionary change".Evol. Dev.8(3): 304–17.DOI:10.1111/j.1525-142X.2006.00101.x.PMID 16686641.

- ↑O'Neil, Dennis (2008).Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium Model.The synthetic theory of evolution: An introduction to modern evolutionary concepts and theories.Behavioral Sciences Department, Palomar College. 2008-01-06 कथं।

- ↑Bright, Kerry (2006).Causes of evolution.Teach Evolution and Make It Relevant.National Science Foundation. 2007-12-30 कथं।

- ↑५४.०५४.१Whitlock M (2003). "Fixation probability and time in subdivided populations".Genetics164(2): 767–79.PMID 12807795.

- ↑Ohta T (2002). "Near-neutrality in evolution of genes and gene regulation".PNAS99(25): 16134–37.DOI:10.1073/pnas.252626899.PMID 12461171.

- ↑५६.०५६.१५६.२Hurst LD (February 2009). "Fundamental concepts in genetics: genetics and the understanding of selection".Nat. Rev. Genet.10(2): 83–93.DOI:10.1038/nrg2506.PMID 19119264.

- ↑Haldane J (1959). "The theory of natural selection today".Nature183(4663): 710–13.DOI:10.1038/183710a0.PMID 13644170.

- ↑Hoekstra H, Hoekstra J, Berrigan D, Vignieri S, Hoang A, Hill C, Beerli P, Kingsolver J (2001). "Strength and tempo of directional selection in the wild".Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.98(16): 9157–60.DOI:10.1073/pnas.161281098.PMID 11470913.

- ↑Felsenstein (1979). "Excursions along the Interface between Disruptive and Stabilizing Selection".Genetics93(3): 773–95.PMID 17248980.

- ↑Andersson M, Simmons L (2006). "Sexual selection and mate choice".Trends Ecol. Evol. (Amst.)21(6): 296–302.DOI:10.1016/j.tree.2006.03.015.PMID 16769428.

- ↑Kokko H, Brooks R, McNamara J, Houston A (2002). "The sexual selection continuum".Proc. Biol. Sci.269(1498): 1331–40.DOI:10.1098/rspb.2002.2020.PMID 12079655.

- ↑Hunt J, Brooks R, Jennions M, Smith M, Bentsen C, Bussière L (2004). "High-quality male field crickets invest heavily in sexual display but die young".Nature432(7020): 1024–27.DOI:10.1038/nature03084.PMID 15616562.

- ↑Odum, EP (1971) Fundamentals of ecology, third edition, Saunders New York

- ↑६४.०६४.१Gould SJ (1998). "Gulliver's further travels: the necessity and difficulty of a hierarchical theory of selection".Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond., B, Biol. Sci.353(1366): 307–14.DOI:10.1098/rstb.1998.0211.PMID 9533127.

- ↑Mayr E (1997). "The objects of selection".Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.94(6): 2091–94.DOI:10.1073/pnas.94.6.2091.PMID 9122151.

- ↑Maynard Smith J (1998). "The units of selection".Novartis Found. Symp.213:203–11; discussion 211–17.PMID 9653725.

- ↑Hickey DA (1992). "Evolutionary dynamics of transposable elements in prokaryotes and eukaryotes".Genetica86(1–3): 269–74.DOI:10.1007/BF00133725.PMID 1334911.

- ↑Gould SJ, Lloyd EA (1999). "Individuality and adaptation across levels of selection: how shall we name and generalize the unit of Darwinism?".Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.96(21): 11904–09.DOI:10.1073/pnas.96.21.11904.PMID 10518549.

- ↑Lande R (1989). "Fisherian and Wrightian theories of speciation".Genome31(1): 221–27.PMID 2687093.

- ↑Otto S, Whitlock M (1997). "The probability of fixation in populations of changing size".Genetics146(2): 723–33.PMID 9178020.

- ↑Charlesworth B (March 2009). "Fundamental concepts in genetics: Effective population size and patterns of molecular evolution and variation".Nat. Rev. Genet.10:195-205.DOI:10.1038/nrg2526.PMID 19204717.

- ↑Nei M (2005). "Selectionism and neutralism in molecular evolution".Mol. Biol. Evol.22(12): 2318–42.DOI:10.1093/molbev/msi242.PMID 16120807.

- ↑Kimura M (1991). "The neutral theory of molecular evolution: a review of recent evidence".Jpn. J. Genet.66(4): 367–86.DOI:10.1266/jjg.66.367.PMID 1954033.

- ↑Kimura M (1989). "The neutral theory of molecular evolution and the world view of the neutralists".Genome31(1): 24–31.PMID 2687096.

- ↑Kreitman M (August 1996). "The neutral theory is dead. Long live the neutral theory".Bioessays18(8): 678–83; discussion 683.DOI:10.1002/bies.950180812.PMID 8760341.

- ↑Leigh E.G. (Jr) (2007). "Neutral theory: a historical perspective.".Journal of Evolutionary Biology20:2075–2091.DOI:10.1111/j.1420-9101.2007.01410.x.

- ↑Morjan C, Rieseberg L (2004). "How species evolve collectively: implications of gene flow and selection for the spread of advantageous alleles".Mol. Ecol.13(6): 1341–56.DOI:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2004.02164.x.PMID 15140081.

- ↑Su H, Qu L, He K, Zhang Z, Wang J, Chen Z, Gu H (2003). "The Great Wall of China: a physical barrier to gene flow?".Heredity90(3): 212–19.DOI:10.1038/sj.hdy.6800237.PMID 12634804.

- ↑Short RV (1975). "The contribution of the mule to scientific thought".J. Reprod. Fertil. Suppl.(23): 359–64.PMID 1107543.

- ↑Gross B, Rieseberg L (2005). "The ecological genetics of homoploid hybrid speciation".J. Hered.96(3): 241–52.DOI:10.1093/jhered/esi026.PMID 15618301.

- ↑Burke JM, Arnold ML (2001). "Genetics and the fitness of hybrids".Annu. Rev. Genet.35:31–52.DOI:10.1146/annurev.genet.35.102401.085719.PMID 11700276.

- ↑Vrijenhoek RC (2006). "Polyploid hybrids: multiple origins of a treefrog species".Curr. Biol.16(7): R245.DOI:10.1016/j.cub.2006.03.005.PMID 16581499.

- ↑Wendel J (2000). "Genome evolution in polyploids".Plant Mol. Biol.42(1): 225–49.DOI:10.1023/A:1006392424384.PMID 10688139.

- ↑८४.०८४.१Sémon M, Wolfe KH (2007). "Consequences of genome duplication".Curr Opin Genet Dev17(6): 505–12.DOI:10.1016/j.gde.2007.09.007.PMID 18006297.

- ↑Comai L (2005). "The advantages and disadvantages of being polyploid".Nat. Rev. Genet.6(11): 836–46.DOI:10.1038/nrg1711.PMID 16304599.

- ↑Soltis P, Soltis D (2000). "The role of genetic and genomic attributes in the success of polyploids".Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.97(13): 7051–57.DOI:10.1073/pnas.97.13.7051.PMID 10860970.

- ↑Boucher Y, Douady CJ, Papke RT, Walsh DA, Boudreau ME, Nesbo CL, Case RJ, Doolittle WF (2003). "Lateral gene transfer and the origins of prokaryotic groups".Annu Rev Genet37:283–328.DOI:10.1146/annurev.genet.37.050503.084247.PMID 14616063.

- ↑Walsh T (2006). "Combinatorial genetic evolution of multiresistance".Curr. Opin. Microbiol.9(5): 476–82.DOI:10.1016/j.mib.2006.08.009.PMID 16942901.

- ↑Kondo N, Nikoh N, Ijichi N, Shimada M, Fukatsu T (2002). "Genome fragment of Wolbachia endosymbiont transferred to X chromosome of host insect".Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.99(22): 14280–85.DOI:10.1073/pnas.222228199.PMID 12386340.

- ↑Sprague G (1991). "Genetic exchange between kingdoms".Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev.1(4): 530–33.DOI:10.1016/S0959-437X(05)80203-5.PMID 1822285.

- ↑Gladyshev EA, Meselson M, Arkhipova IR (May 2008). "Massive horizontal gene transfer in bdelloid rotifers".Science (journal)320(5880): 1210–3.DOI:10.1126/science.1156407.PMID 18511688.

- ↑Baldo A, McClure M (1999). "Evolution and horizontal transfer of dUTPase-encoding genes in viruses and their hosts".J. Virol.73(9): 7710–21.PMID 10438861.

- ↑९३.०९३.१Poole A, Penny D (2007). "Evaluating hypotheses for the origin of eukaryotes".Bioessays29(1): 74–84.DOI:10.1002/bies.20516.PMID 17187354.

- ↑Hendry AP, Kinnison MT (2001). "An introduction to microevolution: rate, pattern, process".Genetica112–113:1–8.DOI:10.1023/A:1013368628607.PMID 11838760.

- ↑Leroi AM (2000). "The scale independence of evolution".Evol. Dev.2(2): 67–77.DOI:10.1046/j.1525-142x.2000.00044.x.PMID 11258392.

- ↑(Gould 2002, pp. 657–658)

- ↑Gould SJ (July 1994). "Tempo and mode in the macroevolutionary reconstruction of Darwinism".Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.91(15): 6764–71.PMID 8041695.

- ↑Jablonski, D. (2000). "Micro- and macroevolution: scale and hierarchy in evolutionary biology and paleobiology".Paleobiology26(sp4): 15–52.DOI:[15:MAMSAH2.0.CO;2 10.1666/0094-8373(2000)26[15:MAMSAH]2.0.CO;2].

- ↑Michael J. Dougherty.Is the human race evolving or devolving?Scientific AmericanJuly 20, 1998.

- ↑TalkOrigins Archiveresponse toCreationistclaims -Claim CB932: Evolution of degenerate forms

- ↑Carroll SB (2001). "Chance and necessity: the evolution of morphological complexity and diversity".Nature409(6823): 1102–09.DOI:10.1038/35059227.PMID 11234024.

- ↑Whitman W, Coleman D, Wiebe W (1998). "Prokaryotes: the unseen majority".Proc Natl Acad Sci U S a95(12): 6578–83.DOI:10.1073/pnas.95.12.6578.PMID 9618454.

- ↑१०३.०१०३.१Schloss P, Handelsman J (2004). "Status of the microbial census".Microbiol Mol Biol Rev68(4): 686–91.DOI:10.1128/MMBR.68.4.686-691.2004.PMID 15590780.

- ↑Nealson K (1999). "Post-Viking microbiology: new approaches, new data, new insights".Orig Life Evol Biosph29(1): 73–93.DOI:10.1023/A:1006515817767.PMID 11536899.

- ↑Orr H (2005). "The genetic theory of adaptation: a brief history".Nat. Rev. Genet.6(2): 119–27.DOI:10.1038/nrg1523.PMID 15716908.

- ↑Nakajima A, Sugimoto Y, Yoneyama H, Nakae T (2002). "High-level fluoroquinolone resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa due to interplay of the MexAB-OprM efflux pump and the DNA gyrase mutation".Microbiol. Immunol.46(6): 391–95.PMID 12153116.

- ↑Blount ZD, Borland CZ, Lenski RE (June 2008). "Inaugural Article: Historical contingency and the evolution of a key innovation in an experimental population of Escherichia coli".Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.105(23): 7899–7906.DOI:10.1073/pnas.0803151105.PMID 18524956.

- ↑Okada H, Negoro S, Kimura H, Nakamura S (1983). "Evolutionary adaptation of plasmid-encoded enzymes for degrading nylon oligomers".Nature306(5939): 203–6.DOI:10.1038/306203a0.PMID 6646204.

- ↑Ohno S (April 1984). "Birth of a unique enzyme from an alternative reading frame of the preexisted, internally repetitious coding sequence".Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.81(8): 2421–5.DOI:10.1073/pnas.81.8.2421.PMID 6585807.

- ↑Copley SD (June 2000). "Evolution of a metabolic pathway for degradation of a toxic xenobiotic: the patchwork approach".Trends Biochem. Sci.25(6): 261–5.PMID 10838562.

- ↑Crawford RL, Jung CM, Strap JL (October 2007). "The recent evolution of pentachlorophenol (PCP)-4-monooxygenase (PcpB) and associated pathways for bacterial degradation of PCP".Biodegradation18(5): 525–39.DOI:10.1007/s10532-006-9090-6.PMID 17123025.

- ↑११२.०११२.१(Gould 2002, pp. 1235–1236)

- ↑Piatigorsky J, Kantorow M, Gopal-Srivastava R, Tomarev SI (1994). "Recruitment of enzymes and stress proteins as lens crystallins".EXS71:241–50.PMID 8032155.

- ↑Wistow G (August 1993). "Lens crystallins: gene recruitment and evolutionary dynamism".Trends Biochem. Sci.18(8): 301–6.DOI:10.1016/0968-0004(93)90041-K.PMID 8236445.

- ↑Bejder L, Hall BK (2002). "Limbs in whales and limblessness in other vertebrates: mechanisms of evolutionary and developmental transformation and loss".Evol. Dev.4(6): 445–58.DOI:10.1046/j.1525-142X.2002.02033.x.PMID 12492145.

- ↑Salesa MJ, Antón M, Peigné S, Morales J (2006). "Evidence of a false thumb in a fossil carnivore clarifies the evolution of pandas".Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.103(2): 379–82.DOI:10.1073/pnas.0504899102.PMID 16387860.

- ↑११७.०११७.१११७.२Fong D, Kane T, Culver D (1995). "Vestigialization and Loss of Nonfunctional Characters".Ann. Rev. Ecol. Syst.26:249–68.DOI:10.1146/annurev.es.26.110195.001341.

- ↑Zhang Z, Gerstein M (August 2004). "Large-scale analysis of pseudogenes in the human genome".Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev.14(4): 328–35.DOI:10.1016/j.gde.2004.06.003.PMID 15261647.

- ↑Jeffery WR (2005). "Adaptive evolution of eye degeneration in the Mexican blind cavefish".J. Hered.96(3): 185–96.DOI:10.1093/jhered/esi028.PMID 15653557.

- ↑Maxwell EE, Larsson HC (2007). "Osteology and myology of the wing of the Emu (Dromaius novaehollandiae), and its bearing on the evolution of vestigial structures".J. Morphol.268(5): 423–41.DOI:10.1002/jmor.10527.PMID 17390336.

- ↑Bejder L, Hall BK (2002). "Limbs in whales and limblessness in other vertebrates: mechanisms of evolutionary and developmental transformation and loss".Evol. Dev.4(6): 445–58.DOI:10.1046/j.1525-142X.2002.02033.x.PMID 12492145.

- ↑Silvestri AR, Singh I (2003). "The unresolved problem of the third molar: would people be better off without it?".Journal of the American Dental Association (1939)134(4): 450–55.DOI:10.1146/annurev.es.26.110195.001341.PMID 12733778.

- ↑Hardin, G.(1960). The Competitive Exclusion Principle.Science131,1292-1297.

- ↑Kocher TD (April 2004). "Adaptive evolution and explosive speciation: the cichlid fish model".Nat. Rev. Genet.5(4): 288–98.DOI:10.1038/nrg1316.PMID 15131652.

- ↑Johnson NA, Porter AH (2001). "Toward a new synthesis: population genetics and evolutionary developmental biology".Genetica112–113:45–58.DOI:10.1023/A:1013371201773.PMID 11838782.

- ↑Baguñà J, Garcia-Fernàndez J (2003). "Evo-Devo: the long and winding road".Int. J. Dev. Biol.47(7–8): 705–13.PMID 14756346.

*Love AC. (2003). "Evolutionary Morphology, Innovation, and the Synthesis of Evolutionary and Developmental Biology".Biology and Philosophy18(2): 309–345.DOI:10.1023/A:1023940220348. - ↑Allin EF (1975). "Evolution of the mammalian middle ear".J. Morphol.147(4): 403–37.DOI:10.1002/jmor.1051470404.PMID 1202224.

- ↑Harris MP, Hasso SM, Ferguson MW, Fallon JF (2006). "The development of archosaurian first-generation teeth in a chicken mutant".Curr. Biol.16(4): 371–77.DOI:10.1016/j.cub.2005.12.047.PMID 16488870.

- ↑Carroll SB (July 2008). "Evo-devo and an expanding evolutionary synthesis: a genetic theory of morphological evolution".Cell134(1): 25–36.DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.030.PMID 18614008.

- ↑Wade MJ (2007). "The co-evolutionary genetics of ecological communities".Nat. Rev. Genet.8(3): 185–95.DOI:10.1038/nrg2031.PMID 17279094.

- ↑Geffeney S, Brodie ED, Ruben PC, Brodie ED (2002). "Mechanisms of adaptation in a predator-prey arms race: TTX-resistant sodium channels".Science297(5585): 1336–9.DOI:10.1126/science.1074310.PMID 12193784.

*Brodie ED, Ridenhour BJ, Brodie ED (2002). "The evolutionary response of predators to dangerous prey: hotspots and coldspots in the geographic mosaic of coevolution between garter snakes and newts".Evolution56(10): 2067–82.PMID 12449493. - ↑Sachs J (2006). "Cooperation within and among species".J. Evol. Biol.19(5): 1415–8; discussion 1426–36.DOI:10.1111/j.1420-9101.2006.01152.x.PMID 16910971.