Usuário:JMagalhães/traduções10

| JMagalhães/traduções10 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Rotavirus | |

| Classificação viral | |

| Group: | I–VII

|

| Groups | |

|

I:dsDNA viruses | |

Umvírusé umagente infecciosomicroscópico capaz de se reproduzir apenas no interior de células vivas. Os vírus podem infectar todos os tipos de organismos, desdeanimaiseplantasaté àsbactériasearchaea.[1]

Desde a publicação do artigo deDmitri Ivanovskyem 1892 onde se descreve um patogénio não-bacteriano responsável pela infecção da planta do tabaco, e da descoberta dovírus mosaico do tabacoporMartinus Beijerinckem 1898, foram já documentados detalhadamente cerca de 5000 vírus,[2]embora existam milhões de tipos diferentes.[3]Os vírus estão presentes em praticamente todos osecossistemasda Terra e são a entidade biológica mais abundante.[4][5]O estudo dos vírus é designado porvirologia,uma especialidade damicrobiologia.

Aspartículas virais,conhecidas comoviriões,são um conjunto de três entidades: omaterial genéticoobtido a partir deADNouARN,moléculasextensas que armazenam informação genética; um revestimento deproteicoque protege estes genes; e nalguns casos umacápsuladelípidosque envolve o revestimento proteico quando se encontra no exterior de uma célula. As formas dos vírus são bastante diversas, desde simples configuraçõeshelicoidaiseicosaedraisaté estruturas bastante complexas. O vírus médio tem cerca de um centésimo das dimensões de uma bactéria comum. A maior parte dos vírus são tão diminutos que é impossível a sua observação directa através de ummicroscópio ótico.

A origem dos vírus durante ahistória evolutiva da vidacontinua em aberto: alguns podem terevoluídoa partir deplasmídeos– moléculas de ADN capazes de se movimentar entre células – enquanto que outros podem ter evoluído a partir das bactérias. Dentro do processo evolutivo, os vírus são um dos mais importantes meios detransferência horizontal de genes,factor que potencia adiversidade genética.[6]

Os vírus propagam-se de várias formas. Nas plantas, os vírus são frequentemente transmitidos entre si porinsectosque se alimentam daseiva,como ospulgõesenquanto que nos animais, podem ser transmitidos através de insectoshemetófagos.Estes organismos mensageiros de patologias são conhecidos comovetores.Osvírus gripaissão transmitidos através da tosse e dos espirros. Osnorovíruserotavírus,a causa mais comum degastroenterite,são propagados através darota orofecale transmitidos entre indivíduos através do contacto físico. OVIHé um dos vários vírus transmitido através decontacto sexuale da exposição a sangue infectado. O número de células anfitriãs que um vírus tem capacidade para infectar +++++++++ completar definição pt de Host range

Viruses spread in many ways; viruses inplantsare often transmitted from plant to plant byinsectsthat feed on thesapof plants, such asaphids;viruses inanimalscan be carried byblood-suckinginsects. These disease-bearing organisms are known asvectors.Influenza virusesare spread by coughing and sneezing.Norovirusandrotavirus,common causes of viralgastroenteritis,are transmitted by thefaecal-oral routeand are passed from person to person by contact, entering the body in food or water.HIVis one of several viruses transmitted throughsexual contactand by exposure to infected blood. The range of host cells that a virus can infect is called its "host range".This can be narrow or, as when a virus is capable of infecting many species, broad.[7]

Uma infecção viral em animais desencadeia umaresposta imunitáriaque normalmente erradica o vírus infeccioso. As respostas imunitárias podem também ser induzidas porvacinação,que confere umaimunidadeadquirida por via artificial a uma determinada infecção viral. No entanto, alguns vírus que estão na origem de infecçõescrónicascomo aSIDAou ahepatite viralsão capazes de contornar a resposta imunológica. Embora osantibióticosnão tenham qualquer efeito sobre os vírus, têm sido desenvolvidos inúmeros medicamentosantivirais.

Etimologia

[editar|editar código-fonte]A palavra tem origem nolatimvirus,referente avenenoe a outras substâncias nocivas. A referência mais antiga que se conhece sobre a sua interpretação moderna como agente de doença infecciosa data de 1728, bastante anterior à demonstração da sua existência em 1892.[8]O termovirulentoem referência a feridas ou úlceras de origem venenosa surge em 1400.[9]O termoviralsurge apenas em 1948,[10]e o termoviriãoem 1959, referindo-se a partículas libertadas das cálulas e capazes de infectar outras células do mesmo tipo.[11][12]

História

[editar|editar código-fonte]

Louis Pasteurnão foi capaz de encontrar um agente patológico que estivesse na origem daraivae especularia sobre um patogénio demasiado pequeno para ser detectado apenas com recurso ao microscópio.[13]Em 1884, omicrobiologistaFrancêsCharles Chamberlandinventou um filtro, conhecido hoje comofiltro Chamberland,com poros mais pequenos do que bactérias. Desta forma, foi possível filtrar uma solução rica em bactérias, removendo-as por completo dessa solução.[14]Em 1892, o bióloo RussoDmitry Ivanovskyfaria uso deste filtro para analisar o que viria a ser conhecido como ovírus do mosaico do tabaco.A sua experiência demonstrou que extractos pulverizados de folhas de plantas de tabaco infectadas continuavam infectados mesmo depois da filtragem. Ivanovsky sugeriu que na origem da infecção poderia eventualmente estar umatoxinaproduzida pelas bactérias, mas não chegaria a seguir esta hipótese.[15]Na época, pensava-se que todos os agentes infecciosos podiam ser retidos nos filtros, e que apenas crescessem num meio com nutrientes, assunção enquadrada nateoria microbiana das doenças.[16]Em 1898, o microbiologista HolandêsMartinus Beijerinckrepetiu a experiência e ficou convencido que a solução filtrada continha um novo agente infecciosos.[17]Observou que esse agente apenas se reproduzia apenas em células que sedividiam,mas como não conseguiu determinar se seria feito de partículas, designou-o apenas por 'contagium vivum fluidum(solução de contágio viva) e reintroduziu a palavravirus.[15]Beijerinck assumiu que os virus estariam presentes no estado líquido, teoria mais tarde desacreditada porWendell Stanley,que demonstrou que se tratavam de partículas.[15]No mesmo ano,Friedrich Loefflerusou um filtro semelhante para isolar o primeiro vírus animal – o vírus dafebre aftosa.[12]

No início do século XX, o bacteriologista InglêsFrederick Twortdescobriu um grupo de vírus capazes de infectar bactérias, hoje designados porbacteriófagos.[18]O microbiologista Franco-CanadianoFélix d'Herelledescobriu vírus que, quando adicionados a bactérias emágar,produziam áreas de bactérias mortas. Diluiu uma suspensão destes vírus e descobriu que as soluções mais diluídas e com menor concentração de vírus, em vez de matar todas as bactérias, formavam pequenas áreas de organismos mortos. A contagem destas áreas multiplicada pelo factor de diluição permitiu-lhe calcular o número de vírus na suspensão incial. Os bacteriófagos eram vistos como potenciais recursos no tratamento de doenças como afebre tifóideou acólera,mas esta hipótese viria a ser abandonada com o desenvolvimento dapenicilina.

[19]

Por volta do fim do século XIX, os vírus eram classificados em termos de infecciosidade, a sua capacidade de serem filtrados, e a sua necessidade de anfitriões vivos. Até então, os vírus apenas tinham sido cultivados em animais e plantas. Em 1906,Ross Granville Harrisoninventou um método para fazer crescertecidoemlinfa,e em 1913 E. Steinhardt, C. Israeli, and R. A. Lambert usaram o mesmo método para fazer crescer vírus devacciniaem fragmentos de tecido da córnea em animais de laboratório.[20]Em 1928, H. B. Maitland and M. C. Maitland cultivaram vírus de vaccinia em soluções de rins animais moídos. ENo entanto, ste método de cultivo só seria universalmente adoptado no início da década de 1950, quando se tornou necessária a produção em grande escala depolioviruspara a produção de vacinas.[21]

Outra inovação dramática teve lugar em 1931, quando o Norte-AmericanoErnest William Goodpastureconsegui cultivar o vírus da gripe em ovos de galinha fertilizados.[22]Em 1949,John F. Enders,Thomas Weller,eFrederick Robbinsfizeram crescer o vírus dapoliomeliteem culturas de células embrionárias humanas e que seria o primeiro vírus a

Another breakthrough came in 1931, when the American pathologistErnest William Goodpasturegrew influenza and several other viruses in fertilized chickens' eggs.[23]In 1949,John F. Enders,Thomas Weller,andFrederick Robbinsgrew polio virus in cultured human embryo cells, the first virus to be grown without using solid animal tissue or eggs. This work enabledJonas Salkto make an effectivepolio vaccine.[24]

The first images of viruses were obtained upon the invention ofelectron microscopyin 1931 by the German engineersErnst RuskaandMax Knoll.[25]In 1935, American biochemist and virologistWendell Meredith Stanleyexamined the tobacco mosaic virus and found it was mostly made of protein.[26]A short time later, this virus was separated into protein and RNA parts.[27] The tobacco mosaic virus was the first to becrystallisedand its structure could therefore be elucidated in detail. The firstX-ray diffractionpictures of the crystallised virus were obtained by Bernal and Fankuchen in 1941. On the basis of her pictures,Rosalind Franklindiscovered the fullDNAstructure of the virus in 1955.[28]In the same year,Heinz Fraenkel-ConratandRobley Williamsshowed that purified tobacco mosaic virus RNA and its coat protein can assemble by themselves to form functional viruses, suggesting that this simple mechanism was probably the means through which viruses were created within their host cells.[29]

The second half of the 20th century was the golden age of virus discovery and most of the over 2,000 recognised species of animal, plant, and bacterial viruses were discovered during these years.[30]In 1957,equine arterivirusand the cause ofBovine virus diarrhea(apestivirus) were discovered. In 1963, thehepatitis B viruswas discovered byBaruch Blumberg,[31]and in 1965,Howard Temindescribed the firstretrovirus.Reverse transcriptase,the key enzyme that retroviruses use to translate their RNA into DNA, was first described in 1970, independently byHoward Martin TeminandDavid Baltimore.[32]In 1983Luc Montagnier's team at thePasteur InstituteinFrance,first isolated the retrovirus now called HIV.[33]

Origins

[editar|editar código-fonte]Viruses are found wherever there is life and have probably existed since living cells first evolved.[34]The origin of viruses is unclear because they do not form fossils, somolecular techniqueshave been used to compare the DNA or RNA of viruses and are a useful means of investigating how they arose.[35]There are three main hypotheses that try to explain the origins of viruses:[36][37]

- Regressive hypothesis

- Viruses may have once been small cells thatparasitisedlarger cells. Over time, genes not required by their parasitism were lost. The bacteriarickettsiaandchlamydiaare living cells that, like viruses, can reproduce only inside host cells. They lend support to this hypothesis, as their dependence on parasitism is likely to have caused the loss of genes that enabled them to survive outside a cell. This is also called thedegeneracy hypothesis,[38][39]orreduction hypothesis.[40]

- Cellular origin hypothesis

- Some viruses may have evolved from bits of DNA or RNA that "escaped" from the genes of a larger organism. The escaped DNA could have come fromplasmids(pieces of naked DNA that can movebetweencells) ortransposons(molecules of DNA that replicate and move around to different positionswithinthe genes of the cell).[41]Once called "jumping genes", transposons are examples ofmobile genetic elementsand could be the origin of some viruses. They were discovered in maize byBarbara McClintockin 1950.[42]This is sometimes called thevagrancy hypothesis,[38][43]or theescape hypothesis.[40]

- Coevolution hypothesis

- This is also called thevirus-first hypothesis[40]and proposes that viruses may have evolved from complex molecules of protein andnucleic acidat the same time as cells first appeared on earth and would have been dependent on cellular life for billions of years.Viroidsare molecules of RNA that are not classified as viruses because they lack a protein coat. However, they have characteristics that are common to several viruses and are often called subviral agents.[44]Viroids are important pathogens of plants.[45]They do not code for proteins but interact with the host cell and use the host machinery for their replication.[46]Thehepatitis delta virusof humans has an RNAgenomesimilar to viroids but has a protein coat derived from hepatitis B virus and cannot produce one of its own. It is, therefore, a defective virus and cannot replicate without the help of hepatitis B virus.[47]In similar manner, thevirophage'sputnik' is dependent onmimivirus,which infects the protozoanAcanthamoeba castellanii.[48]These viruses that are dependent on the presence of other virus species in the host cell are calledsatellitesand may represent evolutionary intermediates of viroids and viruses.[49][50]

In the past, there were problems with all of these hypotheses: the regressive hypothesis did not explain why even the smallest of cellular parasites do not resemble viruses in any way. The escape hypothesis did not explain the complex capsids and other structures on virus particles. The virus-first hypothesis contravened the definition of viruses in that they require host cells.[40]Viruses are now recognised as ancient and to have origins that pre-date the divergence of life into thethree domains.[51]This discovery has led modern virologists to reconsider and re-evaluate these three classical hypotheses.[51]

The evidence for an ancestral world of RNA cells[52]and computer analysis of viral and host DNA sequences are giving a better understanding of the evolutionary relationships between different viruses and may help identify the ancestors of modern viruses. To date, such analyses have not proved which of these hypotheses is correct.[52]However, it seems unlikely that all currently known viruses have a common ancestor, and viruses have probably arisen numerous times in the past by one or more mechanisms.[53]

Prionsare infectious protein molecules that do not contain DNA or RNA.[54]They can cause infections such asscrapiein sheep,bovine spongiform encephalopathy( "mad cow" disease) in cattle, andchronic wasting diseasein deer; in humansprionic diseasesincludeKuru,Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease,andGerstmann–Sträussler–Scheinker syndrome.[55]They are able to replicate because some proteins can exist in two different shapes and the prion changes the normal shape of a host protein into the prion shape. This starts a chain reaction where each prion protein converts many host proteins into more prions, and these new prions then go on to convert even more protein into prions; all known prion diseases are fatal. Although prions are fundamentally different from viruses and viroids, their discovery gives credence to the theory that viruses could have evolved from self-replicating molecules.[56]

Microbiology

[editar|editar código-fonte]Life properties

[editar|editar código-fonte]Opinions differ on whether viruses are a form oflife,or organic structures that interact with living organisms. They have been described as "organisms at the edge of life",[57]since they resemble organisms in that they possess genes and evolve by natural selection,[58]and reproduce by creating multiple copies of themselves through self-assembly. Although they have genes, they do not have a cellular structure, which is often seen as the basic unit of life. Viruses do not have their ownmetabolism,and require a host cell to make new products. They therefore cannot naturally reproduce outside a host cell[59]– although bacterial species such asrickettsiaandchlamydiaare considered living organisms despite the same limitation.[60][61]Accepted forms of life usecell divisionto reproduce, whereas viruses spontaneously assemble within cells. They differ from autonomous growth ofcrystalsas they inherit genetic mutations while being subject to natural selection. Virus self-assembly within host cells has implications for the study of theorigin of life,as it lends further credence to the hypothesis that life could have started as self-assembling organic molecules.[1]

Structure

[editar|editar código-fonte]

Viruses display a wide diversity of shapes and sizes, calledmorphologies.In general, viruses are much smaller than bacteria. Most viruses that have been studied have a diameter between 20 and 300nanometres.Somefiloviruseshave a total length of up to 1400 nm; their diameters are only about 80 nm.[62]Most viruses cannot be seen with alight microscopeso scanning and transmissionelectron microscopesare used to visualise virions.[63]To increase the contrast between viruses and the background, electron-dense "stains" are used. These are solutions of salts of heavy metals, such astungsten,that scatter the electrons from regions covered with the stain. When virions are coated with stain (positive staining), fine detail is obscured.Negative stainingovercomes this problem by staining the background only.[64]

A complete virus particle, known as a virion, consists of nucleic acid surrounded by a protective coat of protein called acapsid.These are formed from identical protein subunits calledcapsomeres.[65]Viruses can have alipid"envelope" derived from the hostcell membrane.The capsid is made from proteins encoded by the viralgenomeand its shape serves as the basis for morphological distinction.[66][67]Virally coded protein subunits will self-assemble to form a capsid, in general requiring the presence of the virus genome. Complex viruses code for proteins that assist in the construction of their capsid. Proteins associated with nucleic acid are known asnucleoproteins,and the association of viral capsid proteins with viral nucleic acid is called a nucleocapsid. The capsid and entire virus structure can be mechanically (physically) probed throughatomic force microscopy.[68][69]In general, there are four main morphological virus types:

- Helical

- These viruses are composed of a single type of capsomer stacked around a central axis to form a helical structure, which may have a central cavity, or hollow tube. This arrangement results in rod-shaped or filamentous virions: These can be short and highly rigid, or long and very flexible. The genetic material, in general, single-stranded RNA, but ssDNA in some cases, is bound into the protein helix by interactions between the negatively charged nucleic acid and positive charges on the protein. Overall, the length of a helical capsid is related to the length of the nucleic acid contained within it and the diameter is dependent on the size and arrangement of capsomers. The well-studied tobacco mosaic virus is an example of a helical virus.[70]

- Icosahedral

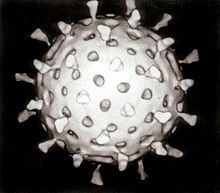

- Most animal viruses are icosahedral or near-spherical with icosahedral symmetry. A regularicosahedronis the optimum way of forming a closed shell from identical sub-units. The minimum number of identical capsomers required is twelve, each composed of five identical sub-units. Many viruses, such as rotavirus, have more than twelve capsomers and appear spherical but they retain this symmetry. Capsomers at the apices are surrounded by five other capsomers and are called pentons. Capsomers on the triangular faces are surrounded by six others and are called hexons.[71]Hexons are in essence flat and pentons, which form the 12 vertices, are curved. The same protein may act as the subunit of both the pentamers and hexamers or they may be composed of different proteins.

- Prolate

- This is an isosahedron elongated along the fivefold axis and is a common arrangement of the heads of bacteriophages. This structure is composed of a cylinder with a cap at either end.[72]

- Envelope

- Some species of virus envelop themselves in a modified form of one of thecell membranes,either the outer membrane surrounding an infected host cell or internal membranes such as nuclear membrane orendoplasmic reticulum,thus gaining an outer lipid bilayer known as a viral envelope. This membrane is studded with proteins coded for by the viral genome and host genome; the lipid membrane itself and any carbohydrates present originate entirely from the host. The influenza virus and HIV use this strategy. Most enveloped viruses are dependent on the envelope for their infectivity.[73]

- Complex

- These viruses possess a capsid that is neither purely helical nor purely icosahedral, and that may possess extra structures such as protein tails or a complex outer wall. Some bacteriophages, such asEnterobacteria phage T4,have a complex structure consisting of an icosahedral head bound to a helical tail, which may have ahexagonalbase plate with protruding protein tail fibres. This tail structure acts like a molecular syringe, attaching to the bacterial host and then injecting the viral genome into the cell.[74]

The poxviruses are large, complex viruses that have an unusual morphology. The viral genome is associated with proteins within a central disk structure known as a nucleoid. The nucleoid is surrounded by a membrane and two lateral bodies of unknown function. The virus has an outer envelope with a thick layer of protein studded over its surface. The whole virion is slightlypleiomorphic,ranging from ovoid to brick shape.[75]Mimivirus is the largest characterised virus, with a capsid diameter of 400 nm. Protein filaments measuring 100 nm project from the surface. The capsid appears hexagonal under an electron microscope, therefore the capsid is probably icosahedral.[76]In 2011, researchers discovered a larger virus on ocean floor of the coast ofLas Cruces,Chile.Provisionally namedMegavirus chilensis,it can be seen with a basic light microscope. [77]

Some viruses that infectArchaeahave complex structures that are unrelated to any other form of virus, with a wide variety of unusual shapes, ranging from spindle-shaped structures, to viruses that resemble hooked rods, teardrops or even bottles. Other archaeal viruses resemble the tailed bacteriophages, and can have multiple tail structures.[78]

Genome

[editar|editar código-fonte]| Property | Parameters |

|---|---|

| Nucleic acid |

|

| Shape |

|

| Strandedness |

|

| Sense |

|

An enormous variety of genomic structures can be seen among viral species; as a group, they contain more structural genomic diversity than plants, animals, archaea, or bacteria. There are millions of different types of viruses,[3]although only about 5,000 of them have been described in detail.[2] A virus has either DNA or RNA genes and is called a DNA virus or a RNA virus, respectively. The vast majority of viruses have RNA genomes. Plant viruses tend to have single-stranded RNA genomes and bacteriophages tend to have double-stranded DNA genomes.[79]

Viral genomes are circular, as in thepolyomaviruses,or linear, as in theadenoviruses.The type of nucleic acid is irrelevant to the shape of the genome. Among RNA viruses and certain DNA viruses, the genome is often divided up into separate parts, in which case it is calledsegmented.For RNA viruses, each segment often codes for only one protein and they are usually found together in one capsid. However, all segments are not required to be in the same virion for the virus to be infectious, as demonstrated bybrome mosaic virusand several other plant viruses.[62]

A viral genome, irrespective of nucleic acid type, is almost always either single-stranded or double-stranded. Single-stranded genomes consist of an unpaired nucleic acid, analogous to one-half of a ladder split down the middle. Double-stranded genomes consist of two complementary paired nucleic acids, analogous to a ladder. The virus particles of some virus families, such as those belonging to theHepadnaviridae,contain a genome that is partially double-stranded and partially single-stranded.[79]

For most viruses with RNA genomes and some with single-stranded DNA genomes, the single strands are said to be eitherpositive-sense(called the plus-strand) ornegative-sense(called the minus-strand), depending on whether or not they are complementary to the viralmessenger RNA(mRNA). Positive-sense viral RNA is in the same sense as viral mRNA and thus at least a part of it can be immediatelytranslatedby the host cell. Negative-sense viral RNA is complementary to mRNA and thus must be converted to positive-sense RNA by anRNA-dependent RNA polymerasebefore translation. DNA nomenclature for viruses with single-sense genomic ssDNA is similar to RNA nomenclature, in that thecoding strandfor the viral mRNA is complementary to it (−), and thenon-coding strandis a copy of it (+).[79]However, several types of ssDNA and ssRNA viruses have genomes that are ambisense in that transcription can occur off both strands in a double-stranded replicative intermediate. Examples includegeminiviruses,which are ssDNA plant viruses andarenaviruses,which are ssRNA viruses of animals.[80]

Genome size varies greatly between species. The smallest viral genomes – the ssDNA circoviruses, familyCircoviridae– code for only two proteins and have a genome size of only 2 kilobases; the largest –mimiviruses– have genome sizes of over 1.2 megabases and code for over one thousand proteins.[81]In general, RNA viruses have smaller genome sizes than DNA viruses because of a higher error-rate when replicating, and have a maximum upper size limit.[35]Beyond this limit, errors in the genome when replicating render the virus useless or uncompetitive. To compensate for this, RNA viruses often have segmented genomes – the genome is split into smaller molecules – thus reducing the chance that an error in a single-component genome will incapacitate the entire genome. In contrast, DNA viruses generally have larger genomes because of the high fidelity of their replication enzymes.[82]Single-strand DNA viruses are an exception to this rule, however, as mutation rates for these genomes can approach the extreme of the ssRNA virus case.[83]

Viruses undergo genetic change by several mechanisms. These include a process calledgenetic driftwhere individual bases in the DNA or RNAmutateto other bases. Most of thesepoint mutationsare "silent" – they do not change the protein that the gene encodes – but others can confer evolutionary advantages such as resistance toantiviral drugs.[84]Antigenic shiftoccurs when there is a major change in thegenomeof the virus. This can be a result ofrecombinationorreassortment.When this happens with influenza viruses,pandemicsmight result.[85]RNA viruses often exist asquasispeciesor swarms of viruses of the same species but with slightly different genome nucleoside sequences. Such quasispecies are a prime target for natural selection.[86]

Segmented genomes confer evolutionary advantages; different strains of a virus with a segmented genome can shuffle and combine genes and produce progeny viruses or (offspring) that have unique characteristics. This is called reassortment orviral sex.[87]

Genetic recombinationis the process by which a strand of DNA is broken and then joined to the end of a different DNA molecule. This can occur when viruses infect cells simultaneously and studies ofviral evolutionhave shown that recombination has been rampant in the species studied.[88]Recombination is common to both RNA and DNA viruses.[89][90]

Replication cycle

[editar|editar código-fonte]Viral populations do not grow through cell division, because they are acellular. Instead, they use the machinery and metabolism of a host cell to produce multiple copies of themselves, and theyassemblein the cell.

Thelife cycle of virusesdiffers greatly between species but there are sixbasicstages in the life cycle of viruses:[91]

- Attachmentis a specific binding between viral capsid proteins and specific receptors on the host cellular surface. This specificity determines the host range of a virus. For example, HIV infects a limited range of humanleucocytes.This is because its surface protein,gp120,specifically interacts with theCD4molecule – achemokine receptor– which is most commonly found on the surface ofCD4+T-Cells.This mechanism has evolved to favour those viruses that infect only cells in which they are capable of replication. Attachment to the receptor can induce the viral envelope protein to undergo changes that results in thefusionof viral and cellular membranes, or changes of non-enveloped virus surface proteins that allow the virus to enter.

- Penetrationfollows attachment: Virions enter the host cell through receptor-mediatedendocytosisormembrane fusion.This is often calledviral entry.The infection of plant and fungal cells is different from that of animal cells. Plants have a rigid cell wall made ofcellulose,and fungi one of chitin, so most viruses can get inside these cells only after trauma to the cell wall.[92]However, nearly all plant viruses (such as tobacco mosaic virus) can also move directly from cell to cell, in the form of single-stranded nucleoprotein complexes, through pores calledplasmodesmata.[93]Bacteria, like plants, have strong cell walls that a virus must breach to infect the cell. However, given that bacterial cell walls are much less thick than plant cell walls due to their much smaller size, some viruses have evolved mechanisms that inject their genome into the bacterial cell across the cell wall, while the viral capsid remains outside.[94]

- Uncoatingis a process in which the viral capsid is removed: This may be by degradation by viralenzymesor host enzymes or by simple dissociation; the end-result is the releasing of the viral genomic nucleic acid.

- Replicationof viruses involves primarily multiplication of the genome. Replication involves synthesis of viral messenger RNA (mRNA) from "early" genes (with exceptions for positive sense RNA viruses), viralprotein synthesis,possible assembly of viral proteins, then viral genome replication mediated by early or regulatory protein expression. This may be followed, for complex viruses with larger genomes, by one or more further rounds of mRNA synthesis: "late" gene expression is, in general, of structural or virion proteins.

- Following the structure-mediated self-assemblyof the virus particles, some modification of the proteins often occurs. In viruses such as HIV, this modification (sometimes called maturation) occursafterthe virus has been released from the host cell.[95]

- Viruses can bereleasedfrom the host cell bylysis,a process that kills the cell by bursting its membrane and cell wall if present: This is a feature of many bacterial and some animal viruses. Some viruses undergo alysogenic cyclewhere the viral genome is incorporated bygenetic recombinationinto a specific place in the host's chromosome. The viral genome is then known as a "provirus"or, in the case of bacteriophages a"prophage".[96]Whenever the host divides, the viral genome is also replicated. The viral genome is mostly silent within the host; however, at some point, the provirus or prophage may give rise to active virus, which may lyse the host cells.[97]Enveloped viruses (e.g., HIV) typically are released from the host cell bybudding.During this process the virus acquires its envelope, which is a modified piece of the host's plasma or other, internal membrane.[98]

The genetic material within virus particles, and the method by which the material is replicated, varies considerably between different types of viruses.

- DNA viruses

- The genome replication of most DNA viruses takes place in the cell'snucleus.If the cell has the appropriate receptor on its surface, these viruses enter the cell sometimes by direct fusion with the cell membrane (e.g., herpesviruses) or – more usually – by receptor-mediated endocytosis. Most DNA viruses are entirely dependent on the host cell's DNA and RNA synthesising machinery, and RNA processing machinery; however, viruses with larger genomes may encode much of this machinery themselves. In eukaryotes the viral genome must cross the cell's nuclear membrane to access this machinery, while in bacteria it need only enter the cell.[99]

- RNA viruses

- Replication usually takes place in thecytoplasm.RNA viruses can be placed into four different groups depending on their modes of replication. Thepolarity(whether or not it can be used directly by ribosomes to make proteins) of single-stranded RNA viruses largely determines the replicative mechanism; the other major criterion is whether the genetic material is single-stranded or double-stranded. All RNA viruses use their ownRNA replicaseenzymes to create copies of their genomes.[100]

- Reverse transcribing viruses

- These have ssRNA (Retroviridae,Metaviridae,Pseudoviridae) or dsDNA (Caulimoviridae,andHepadnaviridae) in their particles. Reverse transcribing viruses with RNA genomes (retroviruses), use a DNA intermediate to replicate, whereas those with DNA genomes (pararetroviruses) use an RNA intermediate during genome replication. Both types use areverse transcriptase,or RNA-dependent DNA polymerase enzyme, to carry out the nucleic acid conversion.Retrovirusesintegrate the DNA produced byreverse transcriptioninto the host genome as a provirus as a part of the replication process; pararetroviruses do not, although integrated genome copies of especially plant pararetroviruses can give rise to infectious virus.[101]They are susceptible toantiviral drugsthat inhibit the reverse transcriptase enzyme, e.g.zidovudineandlamivudine.An example of the first type is HIV, which is a retrovirus. Examples of the second type are theHepadnaviridae,which includes Hepatitis B virus.[102]

Effects on the host cell

[editar|editar código-fonte]The range of structural and biochemical effects that viruses have on the host cell is extensive.[103]These are calledcytopathic effects.[104]Most virus infections eventually result in the death of the host cell. The causes of death include cell lysis, alterations to the cell's surface membrane andapoptosis.[105]Often cell death is caused by cessation of its normal activities because of suppression by virus-specific proteins, not all of which are components of the virus particle.[106]

Some viruses cause no apparent changes to the infected cell. Cells in which the virus islatentand inactive show few signs of infection and often function normally.[107]This causes persistent infections and the virus is often dormant for many months or years. This is often the case withherpes viruses.[108][109]Some viruses, such asEpstein-Barr virus,can cause cells to proliferate without causing malignancy,[110]while others, such aspapillomaviruses,are established causes of cancer.[111]

Host range

[editar|editar código-fonte]Viruses are by far the most abundant biological entities on Earth and they outnumber all the others put together.[112]They infect all types of cellular life including animals, plants,bacteriaandfungi.[2]However, different types of viruses can infect only a limited range of hosts and many are species-specific. Some, such as smallpox virus for example, can infect only one species – in this case humans,[113]and are said to have a narrowhost range.Other viruses, such as rabies virus, can infect different species of mammals and are said to have a broad range.[114]The viruses that infect plants are harmless to animals, and most viruses that infect other animals are harmless to humans.[115]The host range of some bacteriophages is limited to a singlestrainof bacteria and they can be used to trace the source of outbreaks of infections by a method calledphage typing.[116]

Classification

[editar|editar código-fonte]Classification seeks to describe the diversity of viruses by naming and grouping them on the basis of similarities. In 1962,André Lwoff,Robert Horne, andPaul Tournierwere the first to develop a means of virus classification, based on theLinnaeanhierarchical system.[117]This system bases classification onphylum,class,order,family,genus,andspecies.Viruses were grouped according to their shared properties (not those of their hosts) and the type of nucleic acid forming their genomes.[118]Later theInternational Committee on Taxonomy of Viruseswas formed. However, viruses are not classified on the basis of phylum or class, as their small genome size and high rate of mutation makes it difficult to determine their ancestry beyond Order. As such, the Baltimore Classification is used to supplement the more traditional hierarchy.

ICTV classification

[editar|editar código-fonte]TheInternational Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses(ICTV) developed the current classification system and wrote guidelines that put a greater weight on certain virus properties to maintain family uniformity. A unified taxonomy (a universal system for classifying viruses) has been established. The 7th lCTV Report formalised for the first time the concept of the virus species as the lowest taxon (group) in a branching hierarchy of viral taxa.[119]However, at present only a small part of the total diversity of viruses has been studied, with analyses of samples from humans finding that about 20% of the virus sequences recovered have not been seen before, and samples from the environment, such as from seawater and ocean sediments, finding that the large majority of sequences are completely novel.[120]

The general taxonomic structure is as follows:

In the current (2011) ICTV taxonomy, six orders have been established, the Caudovirales, Herpesvirales, Mononegavirales, Nidovirales, Picornavirales and Tymovirales. A seventh order Ligamenvirales has also been proposed. The committee does not formally distinguish betweensubspecies,strains,andisolates.In total there are 6 orders, 87 families, 19 subfamilies, 349 genera, about 2,284 species and over 3,000 types yet unclassified.[121][122][123]

Baltimore classification

[editar|editar código-fonte]

TheNobel Prize-winning biologistDavid Baltimoredevised theBaltimore classificationsystem.[32][124]The ICTV classification system is used in conjunction with the Baltimore classification system in modern virus classification.[125][126][127]

The Baltimore classification of viruses is based on the mechanism ofmRNAproduction. Viruses must generate mRNAs from their genomes to produce proteins and replicate themselves, but different mechanisms are used to achieve this in each virus family. Viral genomes may be single-stranded (ss) or double-stranded (ds), RNA or DNA, and may or may not usereverse transcriptase(RT). In addition, ssRNA viruses may be eithersense(+) or antisense (−). This classification places viruses into seven groups:

As an example of viral classification, thechicken poxvirus,varicella zoster(VZV), belongs to the order Herpesvirales, familyHerpesviridae,subfamilyAlphaherpesvirinae,and genusVaricellovirus.VZV is in Group I of the Baltimore Classification because it is a dsDNA virus that does not use reverse transcriptase.

Role in human disease

[editar|editar código-fonte]

Examples of common human diseases caused by viruses include thecommon cold,influenza,chickenpoxandcold sores.Many serious diseases such asebola,AIDS,avian influenzaandSARSare caused by viruses. The relative ability of viruses to cause disease is described in terms ofvirulence.Other diseases are under investigation as to whether they too have a virus as the causative agent, such as the possible connection betweenhuman herpes virus six(HHV6) and neurological diseases such asmultiple sclerosisandchronic fatigue syndrome.[130]There is controversy over whether theborna virus,previously thought to causeneurologicaldiseases in horses, could be responsible forpsychiatricillnesses in humans.[131]

Viruses have different mechanisms by which they produce disease in an organism, which depends largely on the viral species. Mechanisms at the cellular level primarily include cell lysis, the breaking open and subsequent death of the cell. Inmulticellular organisms,if enough cells die, the whole organism will start to suffer the effects. Although viruses cause disruption of healthyhomeostasis,resulting in disease, they may exist relatively harmlessly within an organism. An example would include the ability of theherpes simplex virus,which causes cold sores, to remain in a dormant state within the human body. This is called latency[132]and is a characteristic of the herpes viruses including Epstein-Barr virus, which causes glandular fever, and varicella zoster virus, which causes chickenpox andshingles.Most people have been infected with at least one of these types of herpes virus.[133]However, these latent viruses might sometimes be beneficial, as the presence of the virus can increase immunity against bacterial pathogens, such asYersinia pestis.[134]

Some viruses can cause life-long orchronicinfections, where the viruses continue to replicate in the body despite the host's defence mechanisms.[135]This is common in hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infections. People chronically infected are known as carriers, as they serve as reservoirs of infectious virus.[136]In populations with a high proportion of carriers, the disease is said to beendemic.[137]

Epidemiology

[editar|editar código-fonte]Viralepidemiologyis the branch of medical science that deals with the transmission and control of virus infections in humans. Transmission of viruses can be vertical, that is from mother to child, or horizontal, which means from person to person. Examples ofvertical transmissioninclude hepatitis B virus and HIV where the baby is born already infected with the virus.[138]Another, more rare, example is the varicella zoster virus, which, although causing relatively mild infections in humans, can be fatal to the foetus and new-born baby.[139]

Horizontal transmissionis the most common mechanism of spread of viruses in populations. Transmission can occur when: body fluids are exchanged during sexual activity, e.g., HIV; blood is exchanged by contaminated transfusion or needle sharing, e.g., hepatitis C; exchange of saliva by mouth, e.g., Epstein-Barr virus; contaminated food or water is ingested, e.g., norovirus;aerosolscontaining virions are inhaled, e.g., influenza virus; and insect vectors such as mosquitoes penetrate the skin of a host, e.g.,dengue. The rate or speed of transmission of viral infections depends on factors that includepopulation density,the number of susceptible individuals, (i.e., those not immune),[140]the quality of healthcare and the weather.[141]

Epidemiology is used to break the chain of infection in populations during outbreaks of viral diseases.[142]Control measures are used that are based on knowledge of how the virus is transmitted. It is important to find the source, or sources, of the outbreak and to identify the virus. Once the virus has been identified, the chain of transmission can sometimes be broken by vaccines. When vaccines are not available sanitation and disinfection can be effective. Often infected people are isolated from the rest of the community and those that have been exposed to the virus placed inquarantine.[143]To control the outbreak offoot and mouth diseasein cattle in Britain in 2001, thousands of cattle were slaughtered.[144]Most viral infections of humans and other animals haveincubation periodsduring which the infection causes no signs or symptoms.[145]Incubation periods for viral diseases range from a few days to weeks but are known for most infections.[146]Somewhat overlapping, but mainly following the incubation period, there is a period of communicability; a time when an infected individual or animal is contagious and can infect another person or animal.[147]This too is known for many viral infections and knowledge the length of both periods is important in the control of outbreaks.[148]When outbreaks cause an unusually high proportion of cases in a population, community or region they are calledepidemics.If outbreaks spread worldwide they are calledpandemics.[149]

Epidemics and pandemics

[editar|editar código-fonte]

Native Americanpopulations were devastated by contagious diseases, in particular,smallpox,brought to the Americas by European colonists. It is unclear how many Native Americans were killed by foreign diseases after the arrival of Columbus in the Americas, but the numbers have been estimated to be close to 70% of the indigenous population. The damage done by this disease significantly aided European attempts to displace and conquer the native population.[150]

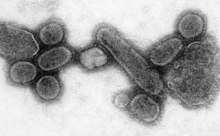

Apandemicis a worldwide epidemic. The1918 flu pandemic,commonly referred to as the Spanish flu, was acategory 5influenza pandemic caused by an unusually severe and deadly influenza A virus. The victims were often healthy young adults, in contrast to most influenza outbreaks, which predominantly affect juvenile, elderly, or otherwise-weakened patients.[151]The Spanish flu pandemic lasted from 1918 to 1919. Older estimates say it killed 40–50 million people,[152]while more recent research suggests that it may have killed as many as 100 million people, or 5% of the world's population in 1918.[153]

Most researchers believe that HIV originated insub-Saharan Africaduring the 20th century;[154]it is now apandemic,with an estimated 38.6 million people now living with the disease worldwide.[155]TheJoint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS(UNAIDS) and theWorld Health Organization(WHO) estimate that AIDS has killed more than 25 million people since it was first recognised on June 5, 1981, making it one of the most destructiveepidemicsin recorded history.[156]In 2007 there were 2.7 million new HIV infections and 2 million HIV-related deaths.[157]

Several highly lethal viral pathogens are members of theFiloviridae.Filoviruses are filament-like viruses that causeviral hemorrhagic fever,and include theebolaandmarburg viruses.The Marburg virus attracted widespread press attention in April 2005 for an outbreak inAngola.Beginning in October 2004 and continuing into 2005, the outbreak was the world's worst epidemic of any kind of viral hemorrhagic fever.[158]

Cancer

[editar|editar código-fonte]Viruses are an established cause ofcancerin humans and other species. Viral cancers occur only in a minority of infected persons (or animals). Cancer viruses come from a range of virus families, including both RNA and DNA viruses, and so there is no single type of "oncovirus"(an obsolete term originally used for acutely transforming retroviruses). The development of cancer is determined by a variety of factors such as host immunity[159]and mutations in the host.[160]Viruses accepted to cause human cancers include some genotypes ofhuman papillomavirus,hepatitis B virus,hepatitis C virus,Epstein-Barr virus,Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirusandhuman T-lymphotropic virus.The most recently discovered human cancer virus is a polyomavirus (Merkel cell polyomavirus) that causes most cases of a rare form of skin cancer calledMerkel cell carcinoma.[161] Hepatitis viruses can develop into a chronic viral infection that leads toliver cancer.[162][163]Infection by human T-lymphotropic virus can lead totropical spastic paraparesisandadult T-cell leukemia.[164]Human papillomaviruses are an established cause of cancers ofcervix,skin,anus,andpenis.[165]Within theHerpesviridae,Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesviruscausesKaposi's sarcomaand body cavity lymphoma, and Epstein–Barr virus causesBurkitt's lymphoma,Hodgkin’s lymphoma,Blymphoproliferative disorder,andnasopharyngeal carcinoma.[166]Merkel cell polyomavirus closely related toSV40and mouse polyomaviruses that have been used as animal models for cancer viruses for over 50 years.[167]

Host defence mechanisms

[editar|editar código-fonte]The body's first line of defence against viruses is theinnate immune system.This comprises cells and other mechanisms that defend the host from infection in a non-specific manner. This means that the cells of the innate system recognise, and respond to, pathogens in a generic way, but, unlike theadaptive immune system,it does not confer long-lasting or protective immunity to the host.[168]

RNA interferenceis an important innate defence against viruses.[169]Many viruses have a replication strategy that involves double-stranded RNA (dsRNA). When such a virus infects a cell, it releases its RNA molecule or molecules, which immediately bind to a protein complex calleddicerthat cuts the RNA into smaller pieces. A biochemical pathway called the RISC complex is activated, which degrades the viral mRNA and the cell survives the infection. Rotaviruses avoid this mechanism by not uncoating fully inside the cell and by releasing newly produced mRNA through pores in the particle's inner capsid. The genomic dsRNA remains protected inside the core of the virion.[170][171]

When theadaptive immune systemof avertebrateencounters a virus, it produces specificantibodiesthat bind to the virus and render it non-infectious. This is calledhumoral immunity.Two types of antibodies are important. The first, calledIgM,is highly effective at neutralizing viruses but is produced by the cells of the immune system only for a few weeks. The second, calledIgG,is produced indefinitely. The presence of IgM in the blood of the host is used to test for acute infection, whereas IgG indicates an infection sometime in the past.[172]IgG antibody is measured when tests forimmunityare carried out.[173]

A second defence of vertebrates against viruses is calledcell-mediated immunityand involves immune cells known as T cells. The body's cells constantly display short fragments of their proteins on the cell's surface, and, if a T cell recognises a suspicious viral fragment there, the host cell is destroyed bykiller Tcells and the virus-specific T-cells proliferate. Cells such as themacrophageare specialists at thisantigen presentation.[174]The production ofinterferonis an important host defence mechanism. This is a hormone produced by the body when viruses are present. Its role in immunity is complex; it eventually stops the viruses from reproducing by killing the infected cell and its close neighbours.[175]

Not all virus infections produce a protective immune response in this way.HIVevades the immune system by constantly changing the amino acid sequence of the proteins on the surface of the virion. These persistent viruses evade immune control by sequestration, blockade ofantigen presentation,cytokineresistance, evasion ofnatural killer cellactivities, escape fromapoptosis,and antigenic shift.[176]Other viruses, calledneurotropic viruses,are disseminated by neural spread where the immune system may be unable to reach them.

Prevention and treatment

[editar|editar código-fonte]Because viruses use vital metabolic pathways within host cells to replicate, they are difficult to eliminate without using drugs that cause toxic effects to host cells in general. The most effective medical approaches to viral diseases arevaccinationsto provide immunity to infection, andantiviral drugsthat selectively interfere with viral replication.

Vaccines

[editar|editar código-fonte]Vaccinationis a cheap and effective way of preventing infections by viruses. Vaccines were used to prevent viral infections long before the discovery of the actual viruses. Their use has resulted in a dramatic decline in morbidity (illness) and mortality (death) associated with viral infections such aspolio,measles,mumpsandrubella.[177]Smallpox infections have been eradicated.[178]Vaccines are available to prevent over thirteen viral infections of humans,[179]and more are used to prevent viral infections of animals.[180]Vaccines can consist of live-attenuated or killed viruses, or viral proteins (antigens).[181]Live vaccines contain weakened forms of the virus, which do not cause the disease but, nonetheless, confer immunity. Such viruses are called attenuated. Live vaccines can be dangerous when given to people with a weak immunity, (who are described asimmunocompromised), because in these people, the weakened virus can cause the original disease.[182]Biotechnology and genetic engineering techniques are used to produce subunit vaccines. These vaccines use only the capsid proteins of the virus. Hepatitis B vaccine is an example of this type of vaccine.[183]Subunit vaccines are safe forimmunocompromisedpatients because they cannot cause the disease.[184] The yellow fever virus vaccine, a live-attenuated strain called 17D, is probably the safest and most effective vaccine ever generated.[185]

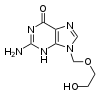

Antiviral drugs

[editar|editar código-fonte]Antiviral drugs are oftennucleoside analogues,(fake DNA building-blocks), which viruses mistakenly incorporate into their genomes during replication. The life-cycle of the virus is then halted because the newly synthesised DNA is inactive. This is because these analogues lack thehydroxyl groups,which, along withphosphorusatoms, link together to form the strong "backbone" of the DNA molecule. This is called DNAchain termination.[186]Examples of nucleoside analogues areaciclovirfor Herpes simplex virus infections andlamivudinefor HIV and Hepatitis B virus infections.Acicloviris one of the oldest and most frequently prescribed antiviral drugs.[187] Other antiviral drugs in use target different stages of the viral life cycle. HIV is dependent on a proteolytic enzyme called theHIV-1 proteasefor it to become fully infectious. There is a large class of drugs calledprotease inhibitorsthat inactivate this enzyme.

Hepatitis C is caused by an RNA virus. In 80% of people infected, the disease ischronic,and without treatment, they areinfectedfor the remainder of their lives. However, there is now an effective treatment that uses the nucleoside analogue drugribavirincombined withinterferon.[188]The treatment of chroniccarriersof the hepatitis B virus by using a similar strategy using lamivudine has been developed.[189]

Infection in other species

[editar|editar código-fonte]Viruses infect all cellular life and, although viruses occur universally, each cellular species has its own specific range that often infect only that species.[190]Some viruses, calledsatellites,can replicate only within cells that have already been infected by another virus.[48]Viruses are important pathogens of livestock. Diseases such as Foot and Mouth Disease andbluetongueare caused by viruses.[191]Companion animals such as cats, dogs, and horses, if not vaccinated, are susceptible to serious viral infections.Canine parvovirusis caused by a small DNA virus and infections are often fatal in pups.[192]Like allinvertebrates,the honey bee is susceptible to many viral infections.[193]However, most viruses co-exist harmlessly in their host and cause no signs or symptoms of disease.[16]

Plants

[editar|editar código-fonte]

There are many types ofplant virus,but often they cause only a loss ofyield,and it is not economically viable to try to control them. Plant viruses are often spread from plant to plant byorganisms,known asvectors.These are normally insects, but somefungi,nematode worms,andsingle-celled organismshave been shown to be vectors. When control of plant virus infections is considered economical, for perennial fruits, for example, efforts are concentrated on killing the vectors and removing alternate hosts such as weeds.[194]Plant viruses are harmless to humans and other animals because they can reproduce only in living plant cells.[195]

Plants have elaborate and effective defence mechanisms against viruses. One of the most effective is the presence of so-called resistance (R) genes. Each R gene confers resistance to a particular virus by triggering localised areas of cell death around the infected cell, which can often be seen with the unaided eye as large spots. This stops the infection from spreading.[196]RNA interference is also an effective defence in plants.[197]When they are infected, plants often produce natural disinfectants that kill viruses, such assalicylic acid,nitric oxide,andreactive oxygen molecules.[198]

Plant virus particles or virus-like particles (VLPs) have applications in bothbiotechnologyandnanotechnology.The capsids of most plant viruses are simple and robust structures and can be produced in large quantities either by the infection of plants or by expression in a variety of heterologous systems. Plant virus particles can be modified genetically and chemically to encapsulate foreign material and can be incorporated into supramolecular structures for use in biotechnology.[199]

Bacteria

[editar|editar código-fonte]

Bacteriophagesare a common and diverse group of viruses and are the most abundant form of biological entity in aquatic environments – there are up to ten times more of these viruses in the oceans than there are bacteria,[200]reaching levels of 250,000,000 bacteriophages permillilitreof seawater.[201]These viruses infect specific bacteria by binding tosurface receptor moleculesand then entering the cell. Within a short amount of time, in some cases just minutes, bacterialpolymerasestarts translating viral mRNA into protein. These proteins go on to become either new virions within the cell, helper proteins, which help assembly of new virions, or proteins involved in cell lysis. Viral enzymes aid in the breakdown of the cell membrane, and, in the case of theT4 phage,in just over twenty minutes after injection over three hundred phages could be released.[202]

The major way bacteria defend themselves from bacteriophages is by producing enzymes that destroy foreign DNA. These enzymes, calledrestriction endonucleases,cut up the viral DNA that bacteriophages inject into bacterial cells.[203]Bacteria also contain a system that usesCRISPRsequences to retain fragments of the genomes of viruses that the bacteria have come into contact with in the past, which allows them to block the virus's replication through a form ofRNA interference.[204][205]This genetic system provides bacteria withacquired immunityto infection.

Archaea

[editar|editar código-fonte]Some viruses replicate withinarchaea:these are double-stranded DNA viruses with unusual and sometimes unique shapes.[4][78]These viruses have been studied in most detail in the thermophilic archaea, particularly the ordersSulfolobalesandThermoproteales.[206]Defences against these viruses may involveRNA interferencefromrepetitive DNAsequences within archaean genomes that are related to the genes of the viruses.[207][208]

Role in aquatic ecosystems

[editar|editar código-fonte]A teaspoon of seawater contains about one million viruses.[209]They are essential to the regulation of saltwater and freshwater ecosystems.[210]Most of these viruses are bacteriophages, which are harmless to plants and animals. They infect and destroy the bacteria in aquatic microbial communities, comprising the most important mechanism ofrecycling carbonin the marine environment. The organic molecules released from the bacterial cells by the viruses stimulates fresh bacterial and algal growth.[211]

Microorganisms constitute more than 90% of the biomass in the sea. It is estimated that viruses kill approximately 20% of this biomass each day and that there are 15 times as many viruses in the oceans as there are bacteria andarchaea.Viruses are the main agents responsible for the rapid destruction of harmfulalgal blooms,[212]which often kill other marine life.[213] The number of viruses in the oceans decreases further offshore and deeper into the water, where there are fewer host organisms.[214]

The effects of marine viruses are far-reaching; by increasing the amount ofphotosynthesisin the oceans, viruses are indirectly responsible for reducing the amount ofcarbon dioxidein the atmosphere by approximately 3gigatonnesof carbon per year.[214]

Like any organism,marine mammalsare susceptible to viral infections. In 1988 and 2002, thousands ofharbour sealswere killed in Europe byphocine distemper virus.[215]Many other viruses, includingcaliciviruses,herpesviruses,adenovirusesandparvoviruses,circulate in marine mammal populations.[214]

Role in evolution

[editar|editar código-fonte]Viruses are an important natural means of transferring genes between different species, which increasesgenetic diversityand drives evolution.[6]It is thought that viruses played a central role in the early evolution, before the diversification of bacteria, archaea and eukaryotes and at the time of thelast universal common ancestorof life on Earth.[216]Viruses are still one of the largest reservoirs of unexploredgenetic diversityon Earth.[214]

Applications

[editar|editar código-fonte]Life sciences and medicine

[editar|editar código-fonte]

Viruses are important to the study ofmolecularandcellular biologyas they provide simple systems that can be used to manipulate and investigate the functions of cells.[217]The study and use of viruses have provided valuable information about aspects of cell biology.[218]For example, viruses have been useful in the study ofgeneticsand helped our understanding of the basic mechanisms ofmolecular genetics,such asDNA replication,transcription,RNA processing,translation,proteintransport, andimmunology.

Geneticistsoften use viruses asvectorsto introduce genes into cells that they are studying. This is useful for making the cell produce a foreign substance, or to study the effect of introducing a new gene into the genome. In similar fashion,virotherapyuses viruses as vectors to treat various diseases, as they can specifically target cells and DNA. It shows promising use in the treatment of cancer and ingene therapy.Eastern European scientists have usedphage therapyas an alternative to antibiotics for some time, and interest in this approach is increasing, because of the high level ofantibiotic resistancenow found in some pathogenic bacteria.[219] Expression of heterologousproteinsby viruses is the basis of several manufacturing processes that are currently being used for the production of various proteins such as vaccineantigensand antibodies. Industrial processes have been recently developed using viral vectors and a number of pharmaceutical proteins are currently in pre-clinical and clinical trials.[220]

Materials science and nanotechnology

[editar|editar código-fonte]Current trends in nanotechnology promise to make much more versatile use of viruses. From the viewpoint of a materials scientist, viruses can be regarded as organic nanoparticles. Their surface carries specific tools designed to cross the barriers of their host cells. The size and shape of viruses, and the number and nature of the functional groups on their surface, is precisely defined. As such, viruses are commonly used in materials science as scaffolds for covalently linked surface modifications. A particular quality of viruses is that they can be tailored by directed evolution. The powerful techniques developed by life sciences are becoming the basis of engineering approaches towards nanomaterials, opening a wide range of applications far beyond biology and medicine.[221]

Because of their size, shape, and well-defined chemical structures, viruses have been used as templates for organizing materials on the nanoscale. Recent examples include work at theNaval Research LaboratoryinWashington, DC,using Cowpea Mosaic Virus (CPMV) particles to amplify signals inDNA microarraybased sensors. In this application, the virus particles separate thefluorescentdyesused for signalling to prevent the formation of non-fluorescentdimersthat act asquenchers.[222]Another example is the use of CPMV as a nanoscale breadboard for molecular electronics.[223]

Synthetic viruses

[editar|editar código-fonte]Many viruses can be synthesized de novo ( "from scratch" ) and the first synthetic virus was created in 2002.[224]Although somewhat of a misconception, it is not the actual virus that is synthesized, but rather its DNA genome (in case of a DNA virus), or acDNAcopy of its genome (in case of RNA viruses). For many virus families the naked synthetic DNA or RNA (once enzymatically converted back from the synthetic cDNA) is infectious when introduced into a cell. That is, they contain all the necessary information to produce new viruses. This technology is now being used to investigate novel vaccine strategies.[225]The ability to synthesize viruses has far-reaching consequences, since viruses can no longer be regarded as extinct, as long as the information of their genome sequence is known andpermissivecells are available. Currently, the full-length genome sequences of 2408 different viruses (including smallpox) are publicly available at an online database, maintained by theNational Institute of Health.[226]

Weapons

[editar|editar código-fonte]The ability of viruses to cause devastatingepidemicsin human societies has led to the concern that viruses could be weaponised forbiological warfare.Further concern was raised by the successful recreation of the infamous 1918 influenza virus in a laboratory.[227]Thesmallpoxvirus devastated numerous societies throughout history before its eradication. There are officially only two centers in the world that keep stocks of smallpox virus – the Russian Vector laboratory, and the United States Centers for Disease Control.[228]But fears that it may be used as a weapon are not totally unfounded;[228]the vaccine for smallpox has sometimes severe side-effects – during the last years before the eradication of smallpox disease more people became seriously ill as a result of vaccination than did people from smallpox[229]– and smallpox vaccination is no longer universally practiced.[230]Thus, much of the modern human population has almost no established resistance to smallpox.[228]

References

[editar|editar código-fonte]Notes

[editar|editar código-fonte]- ↑abKoonin EV, Senkevich TG, Dolja VV.The ancient Virus World and evolution of cells.Biol. Direct.2006;1:29.doi:10.1186/1745-6150-1-29.PMID 16984643.

- ↑abcDimmock,p. 49

- ↑abBreitbart M, Rohwer F. Here a virus, there a virus, everywhere the same virus?.Trends Microbiol.2005;13(6):278–84.doi:10.1016/j.tim.2005.04.003.PMID 15936660.

- ↑abLawrence CM, Menon S, Eilers BJ,et al..Structural and functional studies of archaeal viruses.J. Biol. Chem..2009;284(19):12599–603.doi:10.1074/jbc.R800078200.PMID 19158076.

- ↑Edwards RA, Rohwer F. Viral metagenomics.Nat. Rev. Microbiol..2005;3(6):504–10.doi:10.1038/nrmicro1163.PMID 15886693.

- ↑abCanchaya C, Fournous G, Chibani-Chennoufi S, Dillmann ML, Brüssow H. Phage as agents of lateral gene transfer.Curr. Opin. Microbiol..2003;6(4):417–24.doi:10.1016/S1369-5274(03)00086-9.PMID 12941415.

- ↑Shors pp. 49–50

- ↑Harper D.The Online Etymology Dictionary.virus;2011 [citado em 23 December 2011].

- ↑Harper D.The Online Etymology Dictionary.virulent;2011 [citado em 23 December 2011].

- ↑Harper D.The Online Etymology Dictionary.viral;2011 [citado em 23 December 2011].

- ↑Harper D.The Online Etymology Dictionary.virion;2011 [citado em 24 December 2011].

- ↑abCasjens S. In: Mahy BWJ and Van Regenmortel MHV.Desk Encyclopedia of General Virology.Boston: Academic Press; 2010.ISBN 0-12-375146-2.p. 167.Erro de citação: Código

<ref>inválido; o nome "isbn0-12-375146-2" é definido mais de uma vez com conteúdos diferentes - ↑Bordenave G. Louis Pasteur (1822–1895).Microbes and Infection / Institut Pasteur.2003;5(6):553–60.doi:10.1016/S1286-4579(03)00075-3.PMID 12758285.

- ↑Shors pp. 76–77

- ↑abcCollier p. 3

- ↑abDimmock p. 4

- ↑Dimmock p.4–5

- ↑Shors p. 589

- ↑D'Herelle F. On an invisible microbe antagonistic toward dysenteric bacilli: brief note by Mr. F. D'Herelle, presented by Mr. Roux.Research in Microbiology.2007;158(7):553–4.doi:10.1016/j.resmic.2007.07.005.PMID 17855060.

- ↑Steinhardt E, Israeli C, Lambert R.A.. Studies on the cultivation of the virus of vaccinia.J. Inf Dis..1913;13(2):294–300.doi:10.1093/infdis/13.2.294.

- ↑Collier p. 4

- ↑Goodpasture EW, Woodruff AM, Buddingh GJ. The cultivation of vaccine and other viruses in the chorioallantoic membrane of chick embryos.Science.1931;74(1919):371–372.doi:10.1126/science.74.1919.371.PMID 17810781.

- ↑Goodpasture EW, Woodruff AM, Buddingh GJ. The cultivation of vaccine and other viruses in the chorioallantoic membrane of chick embryos.Science.1931;74(1919):371–372.doi:10.1126/science.74.1919.371.PMID 17810781.

- ↑Rosen, FS. Isolation of poliovirus—John Enders and the Nobel Prize.New England Journal of Medicine.2004;351(15):1481–83.doi:10.1056/NEJMp048202.PMID 15470207.

- ↑FromNobel Lectures, Physics 1981–1990,(1993) Editor-in-Charge Tore Frängsmyr, Editor Gösta Ekspång, World Scientific Publishing Co., Singapore.

- In 1887, Buist visualised one of the largest, Vaccinia virus, by optical microscopy after staining it. Vaccinia was not known to be a virus at that time. (Buist J.B.Vaccinia and Variola: a study of their life historyChurchill, London)

- ↑Stanley WM, Loring HS. The isolation of crystalline tobacco mosaic virus protein from diseased tomato plants.Science.1936;83(2143):85.doi:10.1126/science.83.2143.85.PMID 17756690.

- ↑Stanley WM, Lauffer MA. Disintegration of tobacco mosaic virus in urea solutions.Science.1939;89(2311):345–347.doi:10.1126/science.89.2311.345.PMID 17788438.

- ↑Creager AN, Morgan GJ. After the double helix: Rosalind Franklin's research on Tobacco mosaic virus.Isis.2008;99(2):239–72.doi:10.1086/588626.PMID 18702397.

- ↑Dimmock p. 12

- ↑Norrby E. Nobel Prizes and the emerging virus concept.Arch. Virol..2008;153(6):1109–23.doi:10.1007/s00705-008-0088-8.PMID 18446425.

- ↑Collier p. 745

- ↑abTemin HM, Baltimore D. RNA-directed DNA synthesis and RNA tumor viruses.Adv. Virus Res..1972 [cited 16 September 2008];17:129–86.doi:10.1016/S0065-3527(08)60749-6.PMID 4348509.

- ↑Barré-Sinoussi, F.et al..Isolation of a T-lymphotropic retrovirus from a patient at risk for acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS).Science.1983;220(4599):868–871.doi:10.1126/science.6189183.PMID 6189183.

- ↑Iyer LM, Balaji S, Koonin EV, Aravind L. Evolutionary genomics of nucleo-cytoplasmic large DNA viruses.Virus Res..2006;117(1):156–84.doi:10.1016/j.virusres.2006.01.009.PMID 16494962.

- ↑abSanjuán R, Nebot MR, Chirico N, Mansky LM, Belshaw R.Viral mutation rates.Journal of Virology.2010;84(19):9733–48.doi:10.1128/JVI.00694-10.PMID 20660197.

- ↑Shors pp. 14–16

- ↑Collier pp. 11–21

- ↑abDimmock p. 16

- ↑Collier p. 11

- ↑abcdMahy WJ & Van Regenmortel MHV (eds).Desk Encyclopedia of General Virology.Oxford: Academic Press; 2009.ISBN 0-12-375146-2.p. 24.

- ↑Shors p. 574

- ↑The origin and behavior of mutable loci in maize.Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A..1950;36(6):344–55.doi:10.1073/pnas.36.6.344.PMID 15430309.

- ↑Collier pp. 11–12

- ↑Dimmock p. 55

- ↑Shors 551–3

- ↑Tsagris EM, de Alba AE, Gozmanova M, Kalantidis K. Viroids.Cell. Microbiol..2008;10(11):2168.doi:10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01231.x.PMID 18764915.

- ↑Shors p. 492–3

- ↑abLa Scola B, Desnues C, Pagnier I, Robert C, Barrassi L, Fournous G, Merchat M, Suzan-Monti M, Forterre P, Koonin E, Raoult D. The virophage as a unique parasite of the giant mimivirus.Nature.2008;455(7209):100–4.doi:10.1038/nature07218.PMID 18690211.

- ↑Collier p. 777

- ↑Dimmock p. 55–7

- ↑abMahy WJ & Van Regenmortel MHV (eds).Desk Encyclopedia of General Virology.Oxford: Academic Press; 2009.ISBN 0-12-375146-2.p. 28.

- ↑abMahy WJ & Van Regenmortel MHV (eds).Desk Encyclopedia of General Virology.Oxford: Academic Press; 2009.ISBN 0-12-375146-2.p. 26.

- ↑Dimmock pp. 15–16

- ↑Liberski PP. Prion diseases: a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma.Folia Neuropathol.2008;46(2):93–116.PMID 18587704.

- ↑Belay ED and Schonberger LB.Desk Encyclopedia of Human and Medical Virology.Boston: Academic Press; 2009.ISBN 0-12-375147-0.p. 497–504.

- ↑Lupi O, Dadalti P, Cruz E, Goodheart C. Did the first virus self-assemble from self-replicating prion proteins and RNA?.Med. Hypotheses.2007;69(4):724–30.doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2007.03.031.PMID 17512677.

- ↑Rybicki, EP. The classification of organisms at the edge of life, or problems with virus systematics.S Afr J Sci.1990;86:182–186.

- ↑Holmes EC.Viral evolution in the genomic age.PLoS Biol..2007;5(10):e278.doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0050278.PMID 17914905.

- ↑Wimmer E, Mueller S, Tumpey TM, Taubenberger JK.Synthetic viruses: a new opportunity to understand and prevent viral disease.Nature Biotechnology.2009;27(12):1163–72.doi:10.1038/nbt.1593.PMID 20010599.

- ↑Horn M. Chlamydiae as symbionts in eukaryotes.Annual Review of Microbiology.2008;62:113–31.doi:10.1146/annurev.micro.62.081307.162818.PMID 18473699.

- ↑Ammerman NC, Beier-Sexton M, Azad AF.Laboratory maintenance of Rickettsia rickettsii.Current Protocolsin Microbiology.2008;Chapter 3:Unit 3A.5.doi:10.1002/9780471729259.mc03a05s11.PMID 19016440.

- ↑abCollier pp. 33–55

- ↑Collier pp. 33–37

- ↑Kiselev NA, Sherman MB, Tsuprun VL. Negative staining of proteins.Electron Microsc. Rev..1990;3(1):43–72.doi:10.1016/0892-0354(90)90013-I.PMID 1715774.

- ↑Collier p. 40

- ↑Caspar DL, Klug A. Physical principles in the construction of regular viruses.Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol..1962;27:1–24.PMID 14019094.

- ↑Crick FH, Watson JD. Structure of small viruses.Nature.1956;177(4506):473–5.doi:10.1038/177473a0.PMID 13309339.

- ↑Manipulation of individual viruses: friction and mechanical properties.Biophysical Journal.1997;72(3):1396–1403.doi:10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78786-1.PMID 9138585.

- ↑Imaging of viruses by atomic force microscopy.J Gen Virol.2001;82(9):2025–2034.PMID 11514711.

- ↑Collier p. 37

- ↑Collier pp. 40, 42

- ↑Casens, S..Desk Encyclopedia of General Virology.Boston: Academic Press; 2009.ISBN 0-12-375146-2.p. 167–174.

- ↑Collier pp. 42–43

- ↑Rossmann MG, Mesyanzhinov VV, Arisaka F, Leiman PG. The bacteriophage T4 DNA injection machine.Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol..2004;14(2):171–80.doi:10.1016/j.sbi.2004.02.001.PMID 15093831.

- ↑Long GW, Nobel J, Murphy FA, Herrmann KL, Lourie B.Experience with electron microscopy in the differential diagnosis of smallpox.Appl Microbiol.1970;20(3):497–504.PMID 4322005.

- ↑Suzan-Monti M, La Scola B, Raoult D. Genomic and evolutionary aspects of Mimivirus.Virus Research.2006;117(1):145–155.doi:10.1016/j.virusres.2005.07.011.PMID 16181700.

- ↑World’s biggest virus discovered in ocean depths near Chile[citado em 12 October 2011].

- ↑abPrangishvili D, Forterre P, Garrett RA. Viruses of the Archaea: a unifying view.Nat. Rev. Microbiol..2006;4(11):837–48.doi:10.1038/nrmicro1527.PMID 17041631.

- ↑abcCollier pp. 96–99

- ↑Saunders, Venetia A.; Carter, John.Virology: principles and applications.Chichester: John Wiley & Sons; 2007.ISBN 0-470-02387-2.p. 72.

- ↑Van Etten JL, Lane LC, Dunigan DD.DNA viruses: the really big ones (giruses).Annual Review of Microbiology.2010;64:83–99.doi:10.1146/annurev.micro.112408.134338.PMID 20690825.

- ↑Pressing J, Reanney DC. Divided genomes and intrinsic noise.J Mol Evol.1984;20(2):135–46.doi:10.1007/BF02257374.PMID 6433032.

- ↑Duffy S, Holmes EC. Validation of high rates of nucleotide substitution in geminiviruses: phylogenetic evidence from East African cassava mosaic viruses.The Journal of General Virology.2009;90(Pt 6):1539–47.doi:10.1099/vir.0.009266-0.PMID 19264617.

- ↑Pan XP, Li LJ, Du WB, Li MW, Cao HC, Sheng JF. Differences of YMDD mutational patterns, precore/core promoter mutations, serum HBV DNA levels in lamivudine-resistant hepatitis B genotypes B and C.J. Viral Hepat..2007;14(11):767–74.doi:10.1111/j.1365-2893.2007.00869.x.PMID 17927612.

- ↑Hampson AW, Mackenzie JS. The influenza viruses.Med. J. Aust..2006;185(10 Suppl):S39–43.PMID 17115950.

- ↑Metzner KJ. Detection and significance of minority quasispecies of drug-resistant HIV-1.J HIV Ther.2006;11(4):74–81.PMID 17578210.

- ↑Goudsmit, Jaap. Viral Sex. Oxford Univ Press, 1998.ISBN 978-0-19-512496-5ISBN 0-19-512496-0

- ↑Worobey M, Holmes EC. Evolutionary aspects of recombination in RNA viruses.J. Gen. Virol..1999;80 ( Pt 10):2535–43.PMID 10573145.

- ↑Lukashev AN. Role of recombination in evolution of enteroviruses.Rev. Med. Virol..2005;15(3):157–67.doi:10.1002/rmv.457.PMID 15578739.

- ↑Umene K. Mechanism and application of genetic recombination in herpesviruses.Rev. Med. Virol..1999;9(3):171–82.doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-1654(199907/09)9:3<171::AID-RMV243>3.0.CO;2-A.PMID 10479778.

- ↑Collier pp. 75–91

- ↑Dimmock p. 70

- ↑Boevink P, Oparka KJ.Virus-host interactions during movement processes.Plant Physiol..2005;138(4):1815–21.doi:10.1104/pp.105.066761.PMID 16172094.PMC 1183373.

- ↑Dimmock p. 71

- ↑Barman S, Ali A, Hui EK, Adhikary L, Nayak DP. Transport of viral proteins to the apical membranes and interaction of matrix protein with glycoproteins in the assembly of influenza viruses.Virus Res..2001;77(1):61–9.doi:10.1016/S0168-1702(01)00266-0.PMID 11451488.

- ↑Shors pp. 60, 597

- ↑Dimmock, Chapter 15,Mechanisms in virus latentcy,pp.243–259

- ↑Dimmock 185–187

- ↑Shors p. 54; Collier p. 78

- ↑Collier p. 79

- ↑Staginnus C, Richert-Pöggeler KR. Endogenous pararetroviruses: two-faced travelers in the plant genome.Trends in Plant Science.2006;11(10):485–91.doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2006.08.008.PMID 16949329.

- ↑Collier pp. 88–89

- ↑Collier pp. 115–146

- ↑Collier p. 115

- ↑Roulston A, Marcellus RC, Branton PE. Viruses and apoptosis.Annu. Rev. Microbiol..1999;53:577–628.doi:10.1146/annurev.micro.53.1.577.PMID 10547702.

- ↑Alwine JC. Modulation of host cell stress responses by human cytomegalovirus.Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol..2008;325:263–79.doi:10.1007/978-3-540-77349-8_15.PMID 18637511.

- ↑Sinclair J. Human cytomegalovirus: Latency and reactivation in the myeloid lineage.J. Clin. Virol..2008;41(3):180–5.doi:10.1016/j.jcv.2007.11.014.PMID 18164651.

- ↑Jordan MC, Jordan GW, Stevens JG, Miller G. Latent herpesviruses of humans.Ann. Intern. Med..1984;100(6):866–80.PMID 6326635.

- ↑Sissons JG, Bain M, Wills MR. Latency and reactivation of human cytomegalovirus.J. Infect..2002;44(2):73–7.doi:10.1053/jinf.2001.0948.PMID 12076064.

- ↑Barozzi P, Potenza L, Riva G, Vallerini D, Quadrelli C, Bosco R, Forghieri F, Torelli G, Luppi M. B cells and herpesviruses: a model of lymphoproliferation.Autoimmun Rev.2007;7(2):132–6.doi:10.1016/j.autrev.2007.02.018.PMID 18035323.

- ↑Subramanya D, Grivas PD. HPV and cervical cancer: updates on an established relationship.Postgrad Med.2008;120(4):7–13.doi:10.3810/pgm.2008.11.1928.PMID 19020360.