Luca Evanghelistul

| Luca Evanghelistul | |

| |

| Date personale | |

|---|---|

| Născut | Data Necunoscută Antiohia (în prezent Turcia) |

| Decedat | cca. 84 AD Teba, Boeotia (în prezent Grecia) |

| Înmormântat | Grecia |

| Religie | creștinism |

| Ocupație | medic pictor scriitor Cei patru evangheliști iconar evangelist[*] |

| Limbi vorbite | limba greacă modernă[1] |

| Venerație | |

| Venerat în | Biserica Ortodoxă, Biserica Catolică, Biserica Coptă, Biserica Luterană |

| Rămășițe pământești | Basilica di Santa Giustina, Padova, Italia |

| Sărbătoare | 18 octombrie |

| Însemne | Taur înaripat |

| Alte informații | Însoțitorul Sf. Apostol Pavel |

| Modifică date / text | |

Luca Evangelistul (în ebraică לוקא, alfabetizat: Luka, Louka; în greacă Λουκάς, Loukás) este unul dintre cei patru evangheliști, fiind considerat de către tradiția creștină autorul Evangheliei după Luca și a cărții Faptele Apostolilor.

Biografie și tradiție

[modificare | modificare sursă]Era discipol al lui Pavel din Tars, pe care l-ar fi însoțit în călătoriile sale misionare în Asia Mică, Grecia și la Roma.[2][3] El este menționat în trei din Epistolele lui Pavel, inclusiv în Coloseni unde este numit de apostol „prietenul nostru drag, doctorul”.[4][5][6] Cei mai mulți savanți moderni nu acceptă 2 Timotei drept autentic paulină, deci este nesigur din punct de vedere istoric că Luca era companion al lui Pavel (secretarul său).[7][8] Mai mult, când savanții biblici vorbesc despre Luca drept secretar al lui Pavel, nici măcar nu e clar despre care Luca e vorba: Luca cel istoric, Luca paulin sau de presupusul autor al evangheliei.[9]

El ar proveni din Antiohia (în prezent Turcia) și ar fi murit spre sfârșitul secolului I d.Hr. la vârsta de 84 ani în Teba, Grecia.[10][11]

În iconografie și în pictura religioasă, Luca apare însoțit de un taur înaripat, unul dintre cei patru hayyot (ebraică: חַיּוֹת ḥayyōṯ), ființe cerești descrise în viziunea profetului Ezechiel despre carul lui Dumnezeu (merkabah, în ebraică: מֶרְכַּב) în Ezechiel 1:5-12, precum și în cartea Apocalipsei 4:7 din Noul Testament, pe care Părinții Bisericii le-au asociat cu fiecare dintre cei patru Evangheliști.[12]

Părinții Bisericii timpurii, precum Ieronim și Eusebiu au afirmat că el este autorul Evangheliei după Luca și al cărții Faptele Apostolilor, acesta fiind punctul de vedere tradițional al creștinismului.

Iustin Martirul a fost primul apologet creștin care a folosit evangheliile sinoptice,[13] atribute după moartea lui (165 d.Hr.) apostolului Matei și ucenicilor Marcu și Luca (Irineu de Lyon, Adversus Haereses, 180 d.Hr.).[14][15] În Prima apologie (adresată în 155 d.Hr. împăratului roman Antoninus Pius) și în Dialogul cu Trifon (160 d.Hr.), Iustin Martirul menționează „memorii ale apostolilor” (greacă: ἀπομνημονεύματα τῶν ἀποστόλων; transliterare: apomnêmoneúmata tôn apostólôn) și „evanghelii” (greacă: εὐαγγέλιον; transliterare: euangélion), care sunt citite în fiecare duminică (1 Apol. 67.3).[16][17]

Se pare că Iustin nici măcar nu cunoștea Evanghelia după Ioan.[18]

Un alt scriitor creștin timpuriu, Tertulian, considerat drept „părintele teologiei latine”, scrie în lucrarea sa din 207-208 d.Hr. Adversus Marcionem (Contra lui Marcion): „Așadar, dintre apostoli, Ioan și Matei ne insuflă mai întâi credința; în timp ce ucenicii apostolilor, Luca și Marcu, o reînnoiesc după aceea. Toate acestea încep cu aceleași principii de credință.” (Adversus Marcionem 4.2.2)[19]

Anonim

[modificare | modificare sursă]Nu există niciun izvor istoric de încredere care să arate că autorul Evangheliei după Luca s-ar fi numit în mod real Luca, evanghelia sa fiind publicată în mod anonim:[20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29][30][31]

„Ceea ce cei mai mulți nu-și dau seama este că titlurile lor au fost adăugate ulterior de creștini din secolul al II-lea, la decenii întregi după ce aceste cărți fuseseră scrise, pentru a putea pretinde că ele au fost scrise de apostoli. De ce ar fi făcut asta creștinii? Amintiți-vă discuția anterioară asupra formării canonului Noului Testament: numai cărțile care erau apostolice puteau fi incluse. Ce trebuia atunci făcut cu evangheliile care erau citite și larg acceptate ca autorități în timp ce fuseseră scrise în mod anonim, cum a fost cazul celor patru evanghelii din Noul Testament? Ele trebuiau asociate cu apostoli pentru a putea fi incluse în canon, așa că le-au fost atașate nume de apostoli.[32]”—Bart D. Ehrman, Truth and Fiction in The Da Vinci Code: A Historian Reveals What We Really Know about Jesus, Mary Magdalene, and Constantine.

Autorul acestei scrieri nu a fost martor la viața lui Isus și nici măcar nu susține că descrie în evanghelie evenimente la care ar fi fost martor:[24][33][34]

„Ele nu pretind că ar fi fost scrise de martori la viața lui Isus, iar istoricii au recunoscut de mult că ele au fost produse de creștini din a doua sau a treia generație, trăind în alte țări decât Isus (și Iuda), vorbind o limbă diferită (greacă în loc de aramaică), trăind în circumstanțe diferite și adresându-se unui public diferit.[34]”—Bart D. Ehrman, The lost Gospel of Judas Iscariot: a new look at betrayer and betrayed.

De asemenea, acest anonim (autorul evangheliei) nu pare să cunoască epistolele pauline și se pare că nu l-a cunoscut pe apostolul Pavel.[20]

Atât teologia evangheliei plus Faptele Apostolilor, cât și narațiunea istorică din ele sunt incompatibile cu scrisorile lui Pavel.[35]

Identitatea autorului

[modificare | modificare sursă]

Luca s-a născut în Antiohia pe Orontes[36][37][38][39][40][41] un oraș elenistic din provincia romană Siria (în prezent în Turcia), se știe că nu era iudeu, și a fost chemat când Pavel s-a separat de cei circumciși (tăiați împrejur) (Coloseni 4:14; Faptele Apostolilor 28:28-29), în afară de acestea este un om de educație elenă și cu profesia de doctor. Poate că a fost legat și de diaconul "Nicolae, prozelit din Antiohia" (Fapte 6:5).

El a devenit creștin (ucenic) datorită apostolului Pavel, pe care îl însoțește în timpul misiunii sale inițiale în Grecia – din Troada până în orasul Philippi din Macedonia (cca. 51 d.Hr.) după cum indică relatarea din Faptele Apostolilor (16:8-12). Luca a făcut multe călătorii împreună cu Pavel în misiunile sale de evanghelizare, deoarece apostolul era suferind (Galateni 6:11) și putea avea nevoie de ajutorul lui Luca în călătoriile sale.[42]

Luca se află alături de Pavel și în ultima sa călătorie misionară la Ierusalim (c. 58 d.Hr. - Faptele Apostolilor 20:5).[43] După arestarea lui Pavel în acel oraș și în timpul detenției sale prelungite în Cezareea Maritima din apropiere, se presupune că Luca ar fi petrecut mai mult timp în Palestina. Tovarăș loial al apostolului, Luca rămâne cu Pavel și când acesta este întemnițat la Roma, în jurul anului 61 d.Hr.: „Te îmbrățișează Epafras, cel închis împreună cu mine pentru Hristos Iisus, Marcu, Aristarh, Dimas, Luca cei împreună-lucrători cu mine." (Epistola către Filimon 1:23-24). Și după ce toți ceilalți îl părăsesc pe Pavel în închisoarea și suferințele sale finale, Luca este cel care rămâne cu Pavel până la sfârșit: „Numai Luca este cu mine” (2 Timotei 4:11).[44] Cei mai mulți savanți moderni nu acceptă 2 Timotei drept autentic paulină.[7][8]

Cea mai timpurie menționare a lui a fost făcută de apostolul Pavel în Epistola către Filimon, versetul 24. El mai este menționat în Coloseni 4:14 și 2 Timotei 4:11, două scrisori atribuite tradițional-dogmatic lui Pavel.

Următorarea menționare timpurie a lui Luca este în Prologul Anti-Marcionism al Evangheliei după Luca, un document despre care se credea că datează din secolul II, dar care a fost mai nou datat din secolul IV. Helmut Koester, totuși, revendică că următoarea unică parte păstrată în greaca originală putea fi compusă doar la capătul secolului II:

Epifaniu afirmă că Luca a fost unul dintre Cei Șaptezeci (Panarion 51.11), iar Ioan Gură de Aur indică la un punct că "fratele" menționat de Pavel în 2 Corinteni 8:18 este fie Luca, fie Barnaba. J. Wenham afirmă că Luca era "unul din cei Șaptezeci, Emmaus discipol, Luciu de Cirene și rudenia lui Pavel." Nu toți cărturarii sunt așa de încrezători de toate aceste atribute cum este Wenham, mai ales pentru propria declarație a lui Luca la începul Evangheliei după Luca (Luca 1:1–4) în care admite liber că nu este un martor ocular al evenimentelor scrise în Evanghelie. Potrivit tradiției, el a fost parte a celor Șaptezeci de ucenici, un grup de ucenici ai lui Isus, dar în conformitate cu datele de exegeză din lucrările sale nu este un martor ocular mai înainte de anul înălțării la cer al lui Isus.

Dacă se acceptă că Luca este autorul evangheliei ce-i poartă numele și totodată al Faptelor Apostolilor, unele detalii ale vieții sale personale pot fi deduse din context. În timp ce se exclude pe sine însuși dintre cei care erau martori oculari al 'ministerului lui Isus', în mod repetat folosește cuvântul "noi" în descrierea misiunilor Pauline în Faptele Apostolilor, indicând că el era personal acolo în acel timp.[46]

O dovadă similară este că Luca era găzduit în Troa, statul provinciei care include ruinele Troiei antice, unde scrie în Fapte la persoana a treia despre Pavel și călătoriile lui până ei ajung la Troa, unde comută la persoana întâi și la plural. Acestă secțiune cu "noi" din Fapte continuă până grupul pleacă din Filippi, când scrierea lui revine la persoana a treia. Această schimbare are loc din nou când grupul se întoarce la Filippi. Există trei "secțiuni cu noi" în Fapte, toate urmând această regulă.

După martiriul Apostolilor Petru și Pavel la Roma în jurul anului 66 d.Hr.,[47] Luca propovăduiește Evanghelia de-a lungul Galiei, Italiei, Dalmației, Macedoniei și Greciei. Aflat la vârsta de 84 de ani în orașul Teba din Boeotia, Luca suferă martiriul pentru credința în Hristos fiind spânzurat de un măslin.[48][49] Conform istoricului din secolul al XVIII-lea Edward Gibbon, creștinii primari (jumătatea a doua a secolului II d.Hr și prima jumătate a secolului III d.Hr.) credeau ca fuseseră martirizați doar Sf. Petru, Sf. Pavel și Sf. Iacov (fiul lui Zebedei).[50] Restul martirizărilor apostolilor sau chiar toate dintre ele sunt neconfirmate istoric.[51][52]

În timpul cruciadelor, moaștele Sfântului Luca au ajuns la Padova (Italia) și de atunci sunt păstrate în biserica Sf. Iustina, cu excepția craniului, care a fost dus la Catedrala Sf. Vitus din Praga în 1354 d.Hr., prin ordin al împăratului Carol IV.

Apostolul Luca a lăsat drept relicve opt cadavre și nouă cranii.[53][54]

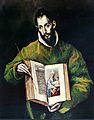

Legenda „Luca o pictează pe Sf. Maria”

[modificare | modificare sursă]Potrivit unei legende, Luca ar fi pictat-o pe Sfânta Maria de mai multe ori. „Luca o pictează pe Sf. Maria” a constituit în ultimele sute de ani tema a numeroase tablouri (El Greco, Derick Baegert, Jan Gossaert, Maarten van Heemskerck, Niklaus Manuel, Rogier van der Weyden ș.a.).

La Mănăstirea Kykkos din Cipru există un tablou atribuit evanghelistului Luca, în care ar fi înfățișată Sf. Maria.

Galerie de imagini

[modificare | modificare sursă]-

El Greco: Doctorul Luca pictând pe Sf. Maria

-

Frontispiciu din Evangeliari de Fulda (cca. 840)

-

Talla de Francisco Ruiz Gijón (1695-1700); Sevilia

Note

[modificare | modificare sursă]- ^ Czech National Authority Database, accesat în

- ^ „Saint Luke | Biography, Feast Day, Patron Saint Of, Facts, & History | Britannica” (în engleză). www.britannica.com. . Accesat în .

- ^ „CatholicSaints.Info » Blog Archive » Catholic Encyclopedia – Gospel of Saint Luke” (în engleză). Accesat în .

- ^ Coloseni 4:14

- ^ Filimon 1:24

- ^ 2 Timotei 4:11

- ^ a b Collins, Raymond F. (). 1 & 2 Timothy and Titus: A Commentary. New Testament Library. Presbyterian Publishing Corporation. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-664-23890-2. Accesat în .

By the end of the twentieth century New Testament scholarship was virtually unanimous in affirming that the Pastoral Epistles were written some time after Paul's death.

- ^ a b Payne, Philip Barton (). Man and Woman, One in Christ: An Exegetical and Theological Study of Paul's Letters. Zondervan Academic. p. 292. ISBN 978-0-310-52532-5. Accesat în .

Many scholars believe that 1 Timothy and the other Pastoral Epistles teach some doctrines that are inconsistent with Paul's theology.2

- ^ Adams, Sean A. (). „The relationships of Paul and Luke”. În Porter, Stanley E.; Land, Christopher D. Paul and His Social Relations. Pauline Studies. Brill. p. 142. ISBN 978-90-04-24211-1. Accesat în .

Finally, in my investigation of the relationship between Luke and Paul, I found substantial ambiguity in the way that scholars have referred to the person of Luke. In studies of authorship, amanuensis, and literary relationship, scholars talk about Luke’s relationship with Paul; however, they rarely (if ever) define who exactly they are talking about. Is it the historical Luke, the Pauline Luke, or “Luke” the supposed author of GLuke and Acts?

- ^ „† Sfântul Apostol și Evanghelist Luca (18 octombrie)”. Pravila. . Accesat în .

- ^ „Sfantul Apostol si Evanghelist Luca”. www.crestinortodox.ro. Accesat în .

- ^ Jerome, Saint (decembrie 2008), Commentary on Matthew (în engleză), CUA Press, ISBN 978-0-8132-0117-7, accesat în

- ^ Skarsaune, Oskar (). The Proof from Prophecy: A Study in Justin Martyr's Proof-text Tradition : Text-type, Provenance, Theological Profile. Novum Testamentum. Supplements. E.J. Brill. pp. 130, 163. ISBN 978-90-04-07468-2. Accesat în .

Justin sometimes had direct access to Matthew and quotes OT texts directly from him. ... (The direct borrowings are most frequent in the Dialogue; in the Apology, Mic 5:1 in 1 Apol. 34:1 may be the only instance.) [130] Diagram of the internal structure of the putative "kerygma source", showing the insertion of scriptural quotation of Mic 5:1 from Mt. 2:6 [163]

- ^ Millard, Alan (). „Authors, Books, and Readers in the Ancient World”. În Rogerson, J.W.; Lieu, Judith M. The Oxford Handbook of Biblical Studies. Oxford University Press. p. 558. ISBN 978-0199254255.

The historical narratives, the Gospels and Acts, are anonymous, the attributions to Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John being first reported in the mid-second century by Irenaeus

- ^ Brant, Jo-Ann A. (). John. Paideia (Grand Rapids, Mich.). Baker Publishing Group. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-8010-3454-1. Accesat în .

- ^ Munier, Charles (), „Justin, Philosopher and Martyr, Apologies”, Revue des sciences religieuses (84/3), pp. 401–413, doi:10.4000/rsr.335, ISSN 0035-2217, accesat în

- ^ Bobichon, Philippe (ianuarie 2005), „Justin martyr : étude stylistique du Dialogue avec Tryphon (suivie d'une comparaison avec l'Apologie et le De resurrectione”, Recherches Augustiniennes et Patristiques, 34, pp. 1–61, doi:10.1484/j.ra.5.102308, ISSN 0484-0887, accesat în

- ^ Koester, Helmut (). Ancient Christian Gospels: Their History and Development. Ancient Christian Gospels: their history and development. SCM Press. pp. 360–361. ISBN 978-0-334-02459-0. Accesat în .

He knew and quoted especially the Gospels of Matthew and Luke; he must have known the Gospel of Mark as well, though there is only one explicit reference to this Gospel (Dial. 106.3); he apparently had no knowledge of the Gospel of John. [...] "The only possible reference to the Gospel of John is the quotation of a saying in 1 Apol. 61.4. [footnote #2]

- ^ McDonald, Lee Martin (), The Formation of the Biblical Canon: Volume 2: The New Testament: Its Authority and Canonicity (în engleză), Bloomsbury Publishing, ISBN 978-0-567-66885-1, accesat în

- ^ a b Soards, Marion L. (). „The Gospel according to Luke”. În Coogan, Michael David; Brettler, Marc Zvi; Newsom, Carol Ann; Perkins, Pheme. The New Oxford Annotated Bible: New Revised Standard Version. Oxford University Press. p. 1467. ISBN 978-0-19-027605-8.

The Third Gospel, traditionally called the Gospel according to Luke, is a unique literary and theological contribution to the story of Jesus Christ. By the late second century, the author of the Gospel and its sequel, the Acts of the Apostles, was identified as Luke, a physician who was a traveling companion and co-worker with Paul (Philem 1.24; Col 4.14). At times Luke is further described as a Syrian from Antioch, but practically nothing else is remembered of the writer of the Third Gospel. Scholarly analysis of the Gospel and Acts raises questions about the attribution of these writings to the Luke who was Paul’s associate. The strongest argument for identifying Luke the physician as the author of the Gospel and Acts is the obscurity of this figure in the New Testament. Yet, even defenders of the traditional identification recognize difficulties with that connection. Though Luke’s familiarity with Judaism is extensive, he seems to have more book-knowledge than practical experience of its particular rituals and beliefs. Similarly, when Luke provides details about Palestinian locations and practices, they exhibit a tendency toward setting the story in an urban environment rather than the predominantly nonurban village culture that Jesus would have known. Above all, Luke never mentions in Acts that Paul wrote letters and only seldom does he use theological themes from the letters of the apostle.

- ^ E P Sanders, The Historical Figure of Jesus, (Penguin, 1995) page 63 - 64.

- ^ E. P. Sanders (). The Historical Figure of Jesus. Penguin Books Limited. p. 103. ISBN 978-0-14-192822-7.

We do not know who wrote the gospels. They presently have headings: 'according to Matthew', 'according to Mark', 'according to Luke' and 'according to John'. The Matthew and John who are meant were two of the original disciples of Jesus. Mark was a follower of Paul, and possibly also of Peter; Luke was one of Paul's converts.5 These men – Matthew, Mark, Luke and John – really lived, but we do not know that they wrote gospels. Present evidence indicates that the gospels remained untitled until the second half of the second century.

- ^ Ehrman, Bart D. (). The New Testament : a historical introduction to the early Christian writings. Oxford University Press, USA. pp. 58–59. ISBN 0-19-515462-2.

Proto-orthodox Christians of the second century, some decades after most of the New Testament books had been written, claimed that their favorite Gospels had been penned by two of Jesus' disciples—Matthew, the tax collector, and John, the beloved disciple—and by two friends of the apostles—Mark, the secretary of Peter, and Luke, the travelling companion of Paul. Scholars today, however, find it difficult to accept this tradition for several reasons.

- ^ a b Ehrman, Bart D. (). Lost Christianities: The Battles for Scripture and the Faiths We Never Knew. Oxford University Press. p. 235. ISBN 978-0-19-518249-1.

Why then do we call them Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John? Because sometime in the second century, when proto-orthodox Christians recognized the need for apostolic authorities, they attributed these books to apostles (Matthew and John) and close companions of apostles (Mark, the secretary of Peter; and Luke, the traveling companion of Paul). Most scholars today have abandoned these identifications,11 and recognize that the books were written by otherwise unknown but relatively well-educated Greek-speaking (and writing) Christians during the second half of the first century.

- ^ Hagner, Donald Alfred (). „MATTHEW, GOSPEL ACCORDING TO.”. În Bromiley, Geoffrey W. International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, Volume III: K-P. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 287. ISBN 978-0-8028-3783-7.

Matthew, like the other three Gospels is an anonymous document.

- ^ Hagner, Donald Alfred (). The New Testament: A Historical and Theological Introduction. Baker Publishing Group. p. 214. ISBN 978-1-4412-4040-8. Accesat în .

Matthew, like all the canonical Gospels, is an anonymous document.

- ^ Senior, Donald; Achtemeier, Paul J.; Karris, Robert J. (). Invitation to the Gospels. Paulist Press. p. 328. ISBN 978-0-8091-4072-5.

All four of the Gospels are anonymous, that is, they themselves do not tell us who their authors were. The Fourth Gospel indicates, as we shall see, that "the disciple Jesus loved", who figures prominently in the second half, was responsible for this Gospel, but even he is anonymous.

- ^ Nickle, Keith Fullerton (). The Synoptic Gospels: An Introduction. Westminster John Knox Press. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-664-22349-6.

We must candidly acknowledge that all three of the Synoptic Gospels are anonymous documents. None of the three gains any importance by association with those traditional figures out of the life of the early church. Neither do they lose anything in importance by being recognized to be anonymous. Throughout this book the traditional names are used to refer to the authors of the first three Gospels, but we shall do so simply as a device of convenience.

- ^ Witherington, Ben (). The Gospel Code: Novel Claims About Jesus, Mary Magdalene and Da Vinci. InterVarsity Press. p. 44. ISBN 978-0-8308-3267-5.

This question is why most scholars don't think Matthew the tax collector wrote the First Gospel.

- ^ Bruce, Frederick Fyvie () [1983]. The Gospel of John: Introduction, Exposition, Notes. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-8028-0883-7.

The Fourth Gospel, like the three Synoptic Gospels, is anonymous: it does not bear its author's name. [...] It is noteworthy that, while the four canonical Gospels could afford to be published anonymously, the apocryphal Gospels which began to appear from the mid-second century onwards claimed (falsely) to be written by apostles or other persons closely associated with the Lord.

- ^ Flanagan, Patrick J. (). The Gospel of Mark Made Easy. Paulist Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-8091-3728-2.

As far as its own author is concerned, the Gospel is anonymous. The same is true of the other Gospels.

- ^ Bart D. Ehrman (2004:111) Truth and Fiction in The Da Vinci Code: A Historian Reveals What We Really Know about Jesus, Mary Magdalene, and Constantine. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Bart D. Ehrman (2004:110) Truth and Fiction in The Da Vinci Code: A Historian Reveals What We Really Know about Jesus, Mary Magdalene, and Constantine. Oxford University Press.

- ^ a b Bart D. Ehrman (2006:143) The lost Gospel of Judas Iscariot: a new look at betrayer and betrayed. Oxford University Press.

- ^ "The principle essay in this regard is P. Vielhauer, 'On the "Paulinism" of Acts', in L.E. Keck and J. L. Martyn (eds.), Studies in Luke-Acts (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1975), 33-50, who suggests that Luke's presentation of Paul was, on several fronts, a contradiction of Paul's own letters (e.g. attitudes on natural theology, Jewish law, christology, eschatology). This has become the standard position in German scholarship, e.g., Conzelmann, Acts; J. Roloff, Die Apostelgeschichte (NTD; Berlin: Evangelische, 1981) 2-5; Schille, Apostelgeschichte des Lukas, 48-52. This position has been challenged most recently by Porter, "The Paul of Acts and the Paul of the Letters: Some Common Misconceptions', in his Paul of Acts, 187-206. See also I.H. Marshall, The Acts of the Apostles (TNTC; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans; Leister: InterVarsity Press, 1980) 42-44; E.E. Ellis, The Gospel of Luke (NCB; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans; London: Marshall, Morgan and Scott, 2nd edn, 1974) 45-47.", Pearson, "Corresponding sense: Paul, dialectic, and Gadamer", Biblical Interpretation Series, p. 101 (2001). Brill.

- ^ Documente ale Noului Testament: Originea lor și Istoria Timpurie, George Milligan, 1913, Macmillan și Co. limitat, p. 149

- ^ Articolul Sfântul Luca - Enciclopedia Catolică Online

- ^ Sfinți: Un Ghid Vizual, Edward Mornin, Lorna Mornin, 2006, Cărțile Eerdmans, p. 74

- ^ Articolul Sfântul Luca - Enciclopedia Catolică

- ^ O Nouă Perpectivă, Alfred Emanuel Smith, 1935, Outlook Pub. Co., p. 792

- ^ Studii ale Noului Testament. I. Doctorul Luca: Autorul celei de-a III-a Evanghelie, Adolf von Harnack, 1907, Williams & Norgate; G.P. Putnam's Sons, p. 5

- ^ „Biblia in limba romana”. eBiblia.ro. Accesat în .

- ^ „Biblia in limba romana”. eBiblia.ro. Accesat în .

- ^ Online, Catholic. „St. Luke - Saints & Angels” (în engleză). Catholic Online. Accesat în .

- ^ Un Comentariu pe Textul Original al Faptele Apostolilor, Horatio Balch Hackett, 1858, Gould și Lincoln; Sheldon, Blakeman & Co., p. 12

- ^ Enciclopædia Britannică, Micropædia vol. 7, p. 554–555. Chicago: Enciclopædia Britannică, Inc, 1998. ISBN 0-85229-633-0.

- ^ „Saint Luke | Biography, Feast Day, Patron Saint Of, Facts, & History | Britannica” (în engleză). www.britannica.com. . Accesat în .

- ^ „† Sfântul Apostol și Evanghelist Luca(18 octombrie)”. Pravila. . Accesat în .

- ^ „Mormantul Sfantului Apostol Luca - Teba”. www.crestinortodox.ro. Accesat în .

- ^ Gibbon, Edward (). „Chapter XVI. The Conduct of the Roman Government toward the Christians, from the Reign of Nero to that of Constantine”. The history of the decline and fall of the Roman empire (în engleză). II. New York: J. & J. Harper for Collins & Hanney. p. 20.

27. In the time of Tertullian and Clemens of Alexandria the glory of martyrdom was confined to St. Peter, St. Paul and St. James. It was gradually bestowed on the rest of the apostles by the more recent Greeks, who prudently selected for the theatre of their preaching and sufferings some remote country beyond the limits of the Roman empire. See Mosheim, p. 81. and Tillemont, Memoires Ecclesiastiques, tom. i. part 3.

- ^ „Were the Disciples Martyred for Believing the Resurrection? A Blast From the Past”. The Bart Ehrman Blog. . Arhivat din original la . Accesat în .

- ^ Wills, Garry (). The Future of the Catholic Church with Pope Francis. Penguin Publishing Group. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-698-15765-1.

(Candida Moss marshals the historical evidence to prove that "we simply don't know how any of the apostles died, much less whether they were martyred.")6

Citează Moss, Candida (). The Myth of Persecution: How Early Christians Invented a Story of Martyrdom. HarperCollins. p. 136. ISBN 978-0-06-210454-0. - ^ Ludovic Lalanne. Curiosités des traditions, des mœurs et des légendes, 1847. / р. 148

- ^ Jacques Albin Simon Collin de Plancy. Dictionnaire critique des reliques et des images miraculeuses, T. 2. 1827 / р. 131

Lectură suplimentară

[modificare | modificare sursă]- Tofană Stelian, Benea Olimpiu-Nicolae, Neacșu Ovidiu-Mihai. Sfântul Luca : Apostol, istoric și evanghelist. Cluj - Napoca, Editura Mega, Vol.2, 2023, 221 p. ISBN 9786063717567

Legături externe

[modificare | modificare sursă]![]() Materiale media legate de Luca Evanghelistul la Wikimedia Commons

Materiale media legate de Luca Evanghelistul la Wikimedia Commons

- Despre Apostolul Luca la enciclopedia OrthodoxWiki

- Portret al Maicii Domnului facut de Apostolul Luca, 29 martie 2004, Adriana Oprea-Popescu, Jurnalul Național

- Sfântul Luca, evanghelistul pildelor Arhivat în , la Wayback Machine., 18 octombrie 2009, Adrian Agachi, Ziarul Lumina

- Mormantul Sfantului Apostol Luca este in Efes?, 29 iunie 2012, Radu Alexandru, CrestinOrtodox.ro