Arachnid

| Arachnids Temporal range:Early Silurian–present

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Left to right:Phidippus mystaceus(Araneae),Pseudoscorpion(Pseudoscorpiones),Hottentotta tamulus(Scorpiones),Ixodes ricinus(Ixodida),Heterophrynus(Amblypygi),Aceria anthocoptes(Trombidiformes),Harvestman(Opiliones),Galeodes caspius(Solifugae), and aWhip scorpion(Thelyphonidae). | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Subphylum: | Chelicerata |

| Class: | Arachnida Lamarck,1801 |

| Orders | |

| |

Thearachnidsare aclassof eight-leggedarthropods.[1]They are a highly successful group of mainly terrestrialinvertebrates:spiders,[2]scorpions,harvestmen,ticks,andmites,and a number of smaller groups.[3]

In 2019, a molecularphylogenystudy puthorseshoe crabsin the Arachnida.[4]

Definition

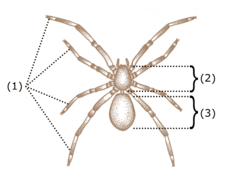

[change|change source]Arachnids aredefined as coming from the class of Arachnida.The requirements for this class is to have two body regions; a cephalothorax and an abdomen; 4 pairs of legs; and 2 pairs of mouthpart appendages, the chelicerae and the pedipalps.[5]

Anatomy

[change|change source]All adult arachnids have four pairs of legs, and arachnids may be easily distinguished frominsectsby this fact, since insects have three pairs of legs. However, arachnids also have two further pairs of appendages that have become adapted for feeding, defense, and sensory perception. The first pair, thechelicerae,serve in feeding and defense. The next pair of appendages, thepedipalpshave been adapted for feeding, locomotion, and/orreproductivefunctions.

Like all arthropods, arachnids have anexoskeleton.They also have an internal structure ofcartilage-like tissue, to which certain muscle groups are attached.[6]

Arachnids have noantennaeor wings. Their body is organized into two parts: thecephalothorax,and theabdomen.

Physiology

[change|change source]There are someadaptationsfor life on land. They have internal respiratory surfaces. These may betrachea(tubes), or a modification of gills into a 'book lung'. This is an internal series oflamellaeused for gas exchange with the air.

Diet and Digestive System

[change|change source]Arachnids are mostlycarnivorous,feeding on the pre-digested bodies of insects and other small animals. Only theharvestmenand somemiteseat solid food particles. Predigestion avoids exposure to internalparasites.[7]Several groups secretevenomfrom specializedglandsto kill prey or enemies. Several mites are externalparasites,and some of them are carriers ofdisease(vectors).

Arachnids pour digestive juices produced in their stomachs over their prey after killing it with their pedipalps and chelicerae. The digestive juices rapidly turn the prey into abrothofnutrientswhich the arachnid sucks into a pre-buccal cavity located immediately in front of the mouth. Behind the mouth is a muscular,pharynx,which acts as a pump, sucking the food through the mouth and on into theoesophagusandstomach.In some arachnids, the oesophagus also acts as an additional pump.

Myth

[change|change source]The wordArachnidacomes from theGreekfor 'spider'. In legend, a girl calledArachnewas turned into a spider by thegoddessAthena.Arachne said she'd win aweavingcontestagainst the goddess. Athena won, but Arachne became angry, and started to weave an insult to the gods. Then Athena turned her into a spider for her disrespect.

Orders

[change|change source]The subdivisions of the arachnids are usually treated asorders.Historically,mitesandtickswere treated as a single order, Acari. However, molecular phylogenetic studies suggest that the two groups do not form a single clade; morphological similarities are probably due to convergence. They are now usually treated as two separate taxa – Acariformes, mites, and Parasitiformes, ticks – which may be ranked as orders or superorders. The arachnid subdivisions are listed below alphabetically; numbers of species are approximate.

- Acariformes– mites (32,000 species)

- Amblypygi– "blunt rump" tail-less whip scorpions with front legs modified intowhip-like sensory structures as long as 25 cm or more (153 species)

- Araneae– spiders (40,000 species)

- †Haptopoda– extinct arachnids apparently part of theTetrapulmonata,the group including spiders and whip scorpions (1 species)

- Opilioacariformes– harvestman-like mites (10 genera)

- Opiliones– phalangids, harvestmen or daddy-long-legs (6,300 species)

- Palpigradi– microwhip scorpions (80 species)

- Parasitiformes– ticks (12,000 species)

- †Phalangiotarbi– extinct arachnids of uncertain affinity (30 species)

- Pseudoscorpionida– pseudoscorpions (3,000 species)

- Ricinulei– ricinuleids, hooded tickspiders (60 species)

- Schizomida– "split middle" whip scorpions with divided exoskeletons (220 species)

- Scorpiones– scorpions (2,000 species)

- Solifugae– solpugids, windscorpions, sun spiders or camel spiders (900 species)

- Thelyphonida(also called Uropygi) – whip scorpions or vinegaroons, forelegs modified into sensory appendages and a long tail on abdomen tip (100 species)

- †Trigonotarbida– extinct (lateSilurianto earlyPermian)

- †Uraraneida– extinct spider-like arachnids, but with a "tail" and nospinnerets(2 species)

- Xiphosura– horseshoe crabs (4 living species)[4]

It is estimated that 98,000 arachnid species have been described, and that there may be up to 600,000 in total.[8]

Images

[change|change source]-

A scorpion (Sc. Maurus Palmatus)

-

Galeodes, acamel spider

-

Awhip scorpion

-

A Pseudoscorpion, on a printed page

-

A harvestman (Rilaena triangularis)

-

A whip spider (Damon diadema)

-

A tick (deer tick)

-

flower, with velvet mites

References

[change|change source]- ↑Ruppert E.E. Fo, R.S. and Barnes R.D. 2004.Invertebrate zoology7 ed, Brooks/Cole. p520ISBN0030259827.

- ↑Foelix, Rainer F. 1996.Biology of spiders.Oxford University Press.ISBN0-19-509593-6.

- ↑Schultz J.W. 2000. A phylogenetic analysis of the arachnid orders based on morphological characters.Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society150:221–265.[1][permanent dead link]

- ↑4.04.1Ballesteros J.A. & Sharma P.P. 2019. A critical appraisal of the placement of Xiphosura (Chelicerata) with account of known sources of phylogenetic error.Systematic Biology.68(6): 896–917.[2]

- ↑"Class Arachnida | Department of Entomology".entomology.unl.edu.Retrieved2021-01-20.

- ↑Kovoor, J. (1978)."Natural calcification of the prosomatic endosternite in the Phalangiidae (Arachnida:Opiliones)".Calcified Tissue Research.26(3): 267–269.doi:10.1007/BF02013269.PMID750069.S2CID23119386.

- ↑Pinto-da-Rocha R. Machado G. & Giribet G. 2007.Harvestmen — the biology of Opiliones.Harvard University PressISBN0-674-02343-9

- ↑Chapman, Arthur D. (2005).Numbers of living species in Australia and the world(PDF).Department of the Environment and Heritage.ISBN978-0-642-56850-2.