Cassini–Huygens

Artist's concept ofCassini'sorbit insertionaround Saturn | |

| Mission type | Cassini:Saturnorbiter Huygens:Titanlander |

|---|---|

| Operator | Cassini:NASA/JPL Huygens:ESA/ASI |

| COSPAR ID | 1997-061A |

| SATCATno. | 25008 |

| Website | |

| Mission duration |

|

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Manufacturer | Cassini:Jet Propulsion Laboratory Huygens:Thales Alenia Space |

| Launch mass | 5,712 kg (12,593 lb)[1][2] |

| Dry mass | 2,523 kg (5,562 lb)[1] |

| Power | ~885 watts (BOL)[1] ~670 watts (2010)[3] ~663 watts (EOM/2017)[1] |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | October 15, 1997, 08:43:00UTC |

| Rocket | Titan IV(401)BB-33 |

| Launch site | Cape CanaveralSLC-40 |

| End of mission | |

| Disposal | Controlled entry into Saturn |

| Last contact | September 15, 2017

|

| Orbital parameters | |

| Reference system | Kronocentric |

| Flyby ofVenus(Gravity assist) | |

| Closest approach | April 26, 1998 |

| Distance | 283 km (176 mi) |

| Flyby ofVenus(Gravity assist) | |

| Closest approach | June 24, 1999 |

| Distance | 623 km (387 mi) |

| Flyby ofEarth-Moonsystem(Gravity assist) | |

| Closest approach | August 18, 1999, 03:28 UTC |

| Distance | 1,171 km (728 mi) |

| Flyby of2685 Masursky(Incidental) | |

| Closest approach | January 23, 2000 |

| Distance | 1,600,000 km (990,000 mi) |

| Flyby ofJupiter(Gravity assist) | |

| Closest approach | December 30, 2000 |

| Distance | 9,852,924 km (6,122,323 mi) |

| Saturnorbiter | |

| Orbital insertion | July 1, 2004, 02:48 UTC |

| Titanlander | |

| Spacecraft component | Huygens |

| Landing date | January 14, 2005 |

Cassini–Huygens,(/kəˈsiːniˈhɔɪɡənz/kə-SEE-neeHOY-gənz) often referred to asCassini,was a joint space-research mission byNASA,theEuropean Space Agency(ESA), and theItalian Space Agency(ASI). Its goal was to studySaturnand its system, including itsringsandmoons,using arobotic spacecraft.The mission included NASA's Cassini space probe and ESA'sHuygens lander,which landed on Saturn's largest moon, Titan in 2005.[5]Cassini was the fourth spacecraft to visit Saturn and the first toorbitaround it, a mission that lasted from 2004 to 2017. The mission was named after astronomersGiovanni CassiniandChristiaan Huygens.

Launched on October 15, 1997, Cassini spent nearly 20 years in space. It orbited Saturn for 13 years, starting from July 1, 2004, and studied the planet and its surroundings during that time.[6]

The journey to Saturn included passing close byVenus(April 1998 and July 1999),Earth(August 1999), theasteroid2685 Masursky,andJupiter(December 2000). Cassini's mission ended on September 15, 2017, when it enteredSaturn's upper atmosphereand burned up to avoid any risk ofcontaminatingSaturn's potentially habitable moonswithmicrobesfrom Earth. The mission exceeded expectations – NASA's Jim Green called Cassini-Huygens a "mission of firsts"[7]that greatly advanced our knowledge of Saturn, its moons, and rings, and expanded our understanding of where life might exist in our solar system.[8]

Cassini's mission was originally planned for four years, from June 2004 to May 2008. It was then extended for two more years until September 2010, called the Cassini Equinox Mission. Later, it received a final extension known as the Cassini Solstice Mission, which lasted another seven years until September 15, 2017. On that date, Cassini was directed to enter Saturn's upper atmosphere and burn up.[9]

TheHuygensmodule traveled with Cassini until it separated from the probe on December 25, 2004. It landed on Titan on January 14, 2005, using aparachute.The separation was helped by the SED (Spin/Eject device), which made it move away at a speed of 0.35 meters per second (1.1 feet per second) and spin at a rate of 7.5 rpm. For about 90 minutes, it sent data back to Earth using Cassini as a relay. This was the first time a spacecraft landed in the outer Solar System and the first time a landing happened on a moon other thanEarth's Moon.

At the end of its mission, Cassini carried out its "Grand Finale": a series of risky passes through gaps between Saturn and its inner rings. This phase aimed to gather as much scientific data as possible before Cassini was destroyed to prevent any risk of contaminating Saturn's moons. This was necessary because if Cassini were to crash into these moons due to power loss or communication issues at the end of its mission, it could potentially contaminate them with Earth microbes. Cassini's mission concluded when it entered Saturn's atmosphere, but scientists will continue analyzing the data it sent back for many years.

Overview

[change|change source]Construction

[change|change source]Scientists and teams from 27 countries worked together to design, build, launch, and operate the Cassini orbiter and Huygens probe.NASA'sJet Propulsion Laboratoryin theUnited Statesmanaged the mission and built the orbiter. TheEuropean Space Research and Technology Centredeveloped the Huygens probe.AérospatialeofFrance,later apart ofThales Alenia Space,put together the probe with help fromvariousEuropean countries. TheItalian Space Agency(ASI) provided important parts for the Cassini orbiter, such asantennasand scientific instruments. NASA added more scientific instruments and electronic parts, with support fromCNESof France. In April 2008, NASA extendedfundingfor ground operations, renaming the mission as theCassini Equinox Mission.More funding extensions were announced in February 2010 for theCassini Solstice Mission.[8][10][11][12][13]

Mission

[change|change source]Launch

[change|change source]Cassini-Huygens launched on October 15, 1997, from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station's Space Launch Complex 40. It used a Titan IVB/Centaur rocket, which included a two-stage Titan IV booster rocket, two solid rocket engines, the Centaur upper stage, and a payload enclosure (fairing).[14]

Venus and Earth flyby's and cruise to Jupiter

[change|change source]The Cassini space probe used gravity to help it travel. It flew byVenustwice, on April 26, 1998, and June 24, 1999, to gain speed. This let Cassini go out to theasteroid beltbefore the Sun's gravity pulled it back.

On August 18, 1999, at 03:28 UTC, Cassini flew byEarth.One hour and 20 minutes earlier, it passed the Moon at 377,000 kilometers and took somecalibrationphotos.

On January 23, 2000, at around 10:00 UTC, Cassini flew by theasteroid2685 Masursky.It took photos five to seven hours before the flyby. The asteroid was estimated to be 15 to 20 kilometers wide.[15]

Jupiter flyby

[change|change source]

Cassini got close toJupiteron December 30, 2000, at 9.7 million kilometers. It took around 26,000 pictures of Jupiter, itsrings,andits moonsduring a six-month flyby. These images made the most detailed global color portrait of Jupiter, showing features as small as 60 kilometers across.

One key finding was about Jupiter'satmospheric circulation.Scientists found that dark "belts" on Jupiter have upwelling air and bright clouds, while the lighter "zones" have sinking air. This was surprising because, on Earth, rising air usually forms clouds.

Cassini also saw a large, dark oval of high atmospheric haze near Jupiter's north pole.Infraredimages showed that the winds near the poles move in opposite directions in different bands.

Cassini's observations of Jupiter's rings showed that the particles in the rings areirregularlyshaped, notspherical.These particles likely come from impacts on Jupiter's moons,MetisandAdrastea,by micrometeorites.

Testing Albert Einstein's Theory of Relativity

[change|change source]On October 10, 2003, the Cassini mission team announced results of tests onAlbert Einstein'sgeneral theory of relativity.They usedradio wavessent from Cassini. These waves passed close to the Sun, and the scientists measured how the frequency changed. According to Einstein's theory, the Sun's gravity curves space-time, causing the radio waves to change frequency.

The experiment found nodeviationsfrom Einstein's theory. Previous tests with theVikingandVoyagerprobes matched Einstein's predictions within one part in a thousand.[16]

New moons of Saturn

[change|change source]

In total, the Cassini mission found seven new moons orbiting Saturn.[17]Using images taken by Cassini, researchers identifiedMethone,Pallene,andPolydeucesin 2004,[18]although later study revealed thatVoyager 2had already photographed Pallene during its flyby of Saturn in 1981.[19]

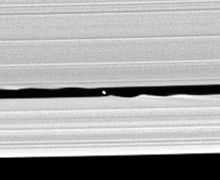

On May 1, 2005, Cassini found a new moon in the Keeler gap ofSaturn's rings.Initially named S/2005 S 1, it was later namedDaphnis.Another moon, originally named S/2007 S 4, was discovered by Cassini on May 30, 2007, and is now known asAnthe.On February 3, 2009, Cassini discovered a sixth moon roughly 500 meters (0.3 miles) in diameter within Saturn's G-ring, now namedAegaeon(formerly S/2008 S 1).[20]On November 2, 2009, Cassini found the seventh moon, labeledS/2009 S 1,roughly 300 meters (980 feet) in diameter in Saturn's B-ring system.[21]

On April 14, 2014, NASA scientists announced the potential start of a new moon forming in Saturn's A Ring.[22]

Phoebe flyby

[change|change source]

On June 11, 2004, Cassini flew by Saturn's moonPhoebefor the first close-up study of this moon.Voyager 2had done a distant flyby in 1981 but did not return detailed images. This was Cassini's only chance to closely study Phoebe due to its orbit around Saturn.

The first close-up images were received on June 12, 2004. Scientists saw that Phoebe's surface looked different from other asteroids visited by spacecraft. Some areas of Phoebe's surface appeared very bright, suggesting there might be a lot of water ice just below the surface.[23]

Cassini's orbital insertion

[change|change source]On July 1, 2004, Cassini flew through the gap between Saturn'sF and G ringsand entered orbit around Saturn, becoming the first spacecraft to do so. This followed a seven-year journey.

TheSaturn Orbital Insertion(SOI) maneuver was complex. Cassini had to turn itsantennaaway from Earth to protect its instruments from ring particles. After crossing the ring plane, it rotated again to point its engine along its flight path and fired the engine to slow down by 622 m/s. This allowed Saturn's gravity to capture Cassini around 8:54 pmPacific Daylight Timeon June 30, 2004. During this maneuver, Cassini passed within 20,000 km (12,000 mi) of Saturn's cloud tops.

Titan flybys

[change|change source]Cassini's first flyby of Saturn's largest moon,Titan,occurred on July 2, 2004, just a day after entering orbit. It came within 339,000 km (211,000 mi) of Titan, capturing images through special filters that could penetrate the moon's thick haze. These images revealed south polar clouds likely made ofmethane,along with surface features of different in brightness.

On October 27, 2004, Cassini performed the first of 45 planned close flybys of Titan, passing 1,200 km (750 mi) above its surface. It transmitted nearly fourgigabitsof data back to Earth, including the first radar images showing Titan's hazy-covered terrain. These images showed Titan's surface to be flat, withelevationsnot exceeding about 50 m (160 ft). The flyby significantly increased the resolution of Titan's imaging, providing pictures up to 100 times clearer than previous ones. Cassini's observations also revealedmethane lakeson Titan's surface, resembling Earth'swater lakes.

Huygens lands on Titan

[change|change source]

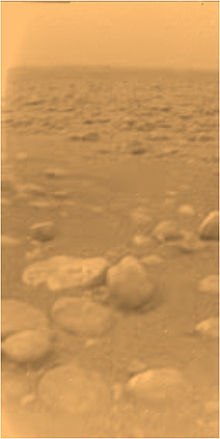

On December 25, 2004, theHuygens probeleft Cassini and traveled toTitan.On January 14, 2005, Huygens landed on Titan, bouncing and sliding to a stop. It discovered pebbles made ofwater iceon an orange surface covered inmethanehaze. Huygens' images revealedriversof liquid methane, drainage channels, and dry lakebeds, indicating recent water activity. Although no permanent lakes were found at the landing site, later Cassini data confirmed lakes in Titan's polar regions.

Huygens sent data back to Earth, and scientists figured out the surface was damp sand made of ice grains, with rounded rocks and pebbles suggesting water movement. The temperature was extremely cold at −179.3 °C; −290.8 °F, and methane took up 5% of the atmosphere. Light levels on Titan were much dimmer than on Earth, casting an orange hue due to Titan's atmospheric haze. After 90 minutes, Huygens stopped sending data, even though it was designed to last longer.[24][25]

Enceladus flybys

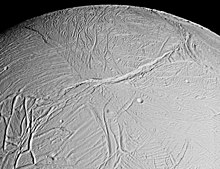

[change|change source]In 2005, during its first two close flybys of the moonEnceladus,Cassini found changes in the localmagnetic fieldthat suggest there's a thin but important atmosphere around Enceladus. Other tests at that time show that the main part of this atmosphere is likelyionizedwater vapor.Cassini also sawgeysersofwater iceshooting out from Enceladus's south pole. This makes scientists think Enceladus could be putting bits of itself into Saturn'sE ring.Scientists began to guess there could be pools of liquid water near the moon's surface that make these eruptions.[26]

On March 12, 2008, Cassini flew close to Enceladus, getting within 50 km of its surface. It went through the plumes coming from the southern geysers and found water,carbon dioxide,and differenthydrocarbonsusing itsmass spectrometer.Cassini also used aninfrared spectrometerto map surface features that are hotter than their surroundings. A problem with its software stopped Cassini from gathering data with itscosmic dustanalyzer.[27][28]

On November 21, 2009, Cassini did its eighth flyby of Enceladus, this time with a different path that took it within 1,600 km of the surface. TheComposite Infrared Spectrograph(CIRS) tool made a map of heat coming from the "tiger stripe" area known as Baghdad Sulcus. This data made a detailed and high-quality picture of the southern side of the moonfacingSaturn.[29]

By April 3, 2014, almost ten years after Cassini started orbiting Saturn, NASA shared proof of a largesaltyocean of liquid waterunder Enceladus's icy shell. This salty ocean touches the moon's rocky center and makes Enceladus a top spot in the Solar System that could havealien life.On June 30, 2014, NASA marked ten years of Cassini's trip to Saturn and its moons. They highlighted finding water activity on Enceladus and other big discoveries.[30][31][32][33]

In September 2015, NASA said data from Cassini show the way Enceladus moves doesn't fit with its core. This led to the idea that the underground ocean under its ice might cover the whole moon.[34]

On October 28, 2015, Cassini flew near Enceladus, getting within 49 km of its surface and going through the ice cloud above the south pole.[35]

On December 14, 2023, scientists said they foundhydrogen cyanideand otherorganic matterin the plumes of Enceladus for the first time. This matter could be very important for life, helping alien microbial life to survive or start on the moon.[36][37]

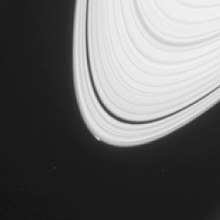

Radio occultations of Saturn's rings

[change|change source]In May 2005, Cassini started a series of radiooccultationexperiments aimed at measuring the size anddistributionof particles in Saturn's rings and studyingSaturn's atmosphere.For more than four months, the spacecraft orbited Saturn in orbits designed for these experiments. During the experiments, Cassini passed behind Saturn's ring plane as observed from Earth and sentradio wavesthrough the ring particles. Scientists on Earth analyzed the radio signals received, saw changes in frequency, phase, and power of the signal to understand the structure and composition of Saturn's rings.

Spokes in rings verified

[change|change source]On September 5, 2005, Cassini captured images showing spokes in Saturn's rings, which were first noticed by visual observerStephen James O'Mearain 1977. TheVoyagerspace probes later confirmed this discovery in the early 1980s.[38][39]

Discovery of lakes on Titan

[change|change source]

Radar pictures taken on July 21, 2006, seem to reveallakesof liquidhydrocarbonslikemethaneandethanein the northern parts of Titan. This marks the first time lakes of this kind have been found anywhere else in theuniversebesidesEarth.These lakes vary in size, ranging from one to one hundred kilometers across.[40]

On March 13, 2007, theJet Propulsion Laboratoryannounced evidence of seas made of methane and ethane in Titan's northern hemisphere. At least one of these seas is bigger than any of theGreat LakesinNorth America.[41]

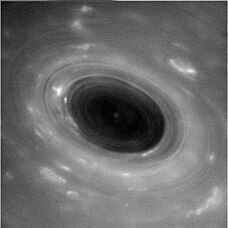

Saturn hurricane

[change|change source]In November 2006, scientists found a storm at Saturn's south pole with a cleareyewall.This is like hurricanes on Earth but is the first time it's been seen on another planet. Unlike hurricanes on Earth, this storm stays in one place at the pole. It's 8,000 kilometers (5,000 miles) wide and 70 kilometers (43 miles) tall. The wind inside blows at 560 kilometers per hour (350 miles per hour).[42]

Iapetus flyby

[change|change source]

On September 10, 2007, Cassini finished its close pass by the peculiar, two-toned,walnut-shaped moon,Iapetus.Photos were taken from 1,600 kilometers (1,000 miles) above its surface. Duringtransmissionof these images to Earth, Cassini was struck by acosmic ray,causing it to briefly entersafe mode.However, all data from the flyby were retrieved.[43]

Mission extension

[change|change source]On April 15, 2008, Cassini got funding for a 27-month extension. It meant doing 60 more orbits around Saturn, with 21 close passes byTitan,seven byEnceladus,six byMimas,eight byTethys,and one each byDione,Rhea,andHelene.[44]The extra mission started on July 1, 2008, and was named theCassini Equinox Missionto match Saturn'sequinox.[45]

Second mission extension

[change|change source]A proposal was sent to NASA for a second mission extension from September 2010 to May 2017, initially named the extended-extended mission or XXM.[46]Approved in February 2010 with a budget of $60 millionannually,it was renamed theCassini Solstice Mission.[47]This phase involved Cassini orbiting Saturn 155 more times and making 54 additional flybys ofTitan,along with 11 more ofEnceladus.

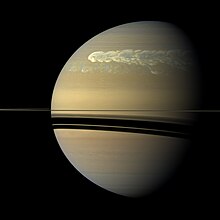

Great Storm of 2010 and aftermath

[change|change source]

On October 25, 2012, Cassini saw the aftermath of a huge storm known as theGreat White Spotthat appears about every 30 years on Saturn.[48]Data from Cassini's compositeinfrared spectrometer(CIRS) showed a powerful burst from the storm, heating Saturn'sstratosphereby 83 K (83 °C; 149 °F) above normal. At the same time, NASA researchers at theGoddard Space Flight CenterinMarylanddetected a sharp increase inethylenegas. Ethylene is a colorless gas rare on Saturn, mostly found on Earth from natural and man-made sources.

The storm was first spotted by Cassini on December 5, 2010, in Saturn's north. It's the first storm of its kind observed by a spacecraft orbiting Saturn and the first seen inthermalinfraredlight, which lets scientists study Saturn's atmosphere temperature and hidden processes. The ethylene spike during the storm was 100 times higher than expected on Saturn. Scientists also found it was the largest and hottestvortexever spotted in the Solar System's stratosphere, initially bigger thanJupiter'sGreat Red Spot.

Venus transit

[change|change source]On December 21, 2012, Cassini watched Venus pass in front of the Sun, a rare event known as a transit. Using its VIMS instrument, Cassini studiedsunlightas itpassed throughVenus's atmosphere.Earlier, VIMS had studied a similar event involving theexoplanetHD 189733 b.[49]

The Day the Earth Smiled

[change|change source]On July 19, 2013, the probe turned towardsEarthto take a picture of our planet andthe Moon.This was part of a special portrait capturing the entire Saturn system in natural light, using multiple images. It was unique because NASA announced in advance that a long-distance photo was being taken.[50][51]The imaging team encouraged people to smile and wave towards the skies. Carolyn Porco, a Cassini scientist, described the moment as an opportunity to "celebrate life on the Pale Blue Dot".[52]

Rhea flyby

[change|change source]On February 10, 2015, the Cassini spacecraft made a close visit toRhea,approaching within 47,000 kilometers (29,000 miles).[53]During this encounter, the spacecraft used its cameras to capture some of the most detailed color images of Rhea to date.[54]

Hyperion flyby

[change|change source]Cassini's most recent flyby of Saturn's moonHyperionoccurred on May 31, 2015, from a distance of about 34,000 kilometers (21,000 miles).[55]

Dione flyby

[change|change source]Cassini's final flyby of Saturn's moonDionetook place on August 17, 2015, at a distance of about 475 kilometers (295 miles). An earlier flyby occurred on June 16.[56]

Saturn's hexagonal storm changes color

[change|change source]Between 2012 and 2016, the hexagonal cloud pattern at Saturn's north pole changed color from mostlyblueto more golden. One idea is that this change is due toseasons:as the pole turned towards the Sun, longer exposure to sunlight might have createdhaze.[57]Before this, from 2004 to 2008, there was less blue color seen across Saturn.[58]

-

2012 and 2016: hexagon color changes

-

2013 and 2017: hexagon color changes

Grand Finale

[change|change source]Cassini's mission ended by flying close to Saturn and going throughits rings.On September 15, 2017, itintentionallyenteredSaturn's atmosphereand was destroyed. This was done to make sureSaturn's moons,whichmight have life,would not get any Earth life on them.[59][60][61][62]

In 2008, several ways to end the mission were considered. A quick crash into Saturn was rated the best choice because it met all the goals and was cheap and easy to do. Another option was to crash into an icy moon, which was also good because it was cheap and could be done at any time.[source?]

In 2013–14, there were issues withNASAgettingU.S. governmentfunds for the Grand Finale. It turned out that the Grand Finale had two phases, which were like having two differentDiscovery Programmissions. This was different from the main Cassini mission. In late 2014, the U.S. government approved the Grand Finale, costing $200 million. This was much less expensive than making two new probes for separate Discovery missions.[63]

On November 29, 2016, the spacecraft flew byTitan,marking the beginning of the Grand Finale phase that ended with its impact on Saturn.[64][65]Another flyby of Titan on April 22, 2017, changed Cassini's orbit to pass through the gap between Saturn and its inner ring on April 26. During this pass, Cassini came within about 3,100 km (1,900 mi) of Saturn's cloud layer and 320 km (200 mi) from the visible edge of the inner ring, capturing images of Saturn's atmosphere and sending data starting the next day.[66]After completing 22 orbits through the gap, the mission ended with Cassini diving into Saturn's atmosphere on September 15. The signal was lost at 11:55:46 UTC on September 15, 2017, approximately 30 seconds later than thought. It is estimated that the spacecraft burned up about 45 seconds after the last transmission.

In September 2018, NASA received anEmmy AwardforOutstanding Original Interactive Programfor itsportrayalof the Cassini mission's Grand Finale at Saturn.[67]

In December 2018,Netflixbroadcasted "NASA's Cassini Mission" as part of their series 7 Days Out, showing the final days of the Cassini mission before the spacecraft crashed into Saturn to complete its Grand Finale.

In January 2019, new research from Cassini's Grand Finale phase was published:

- Scientists measured Saturn's day length: 10 hours, 33 minutes, and 38 seconds.

- Saturn's rings are relatively young, between 10 to 100 million years old.[8]

Missions

[change|change source]The spacecraft's operations were organized into several missions. Each mission had main funding and goals.

- Prime Mission: July 2004 to June 2008.

- Cassini Equinox Mission: July 2008 to September 2010, lasting two years longer.

- Cassini Solstice Mission: October 2010 to April 2017, also known as the XXM mission.

- Grand Finale: April 2017 to September 15, 2017, when the spacecraft was directed into Saturn.

Over 260 scientists from 17countrieshelped to the Cassini–Huygens mission, with thousands more involved in designing, manufacturing, and launching the mission.

-

Saturn byCassini,2016

-

Cassini-Huygensby the numbers

(September 2017) -

Farewell to Saturn and moons (Enceladus,Epimetheus,Janus,Mimas,PandoraandPrometheus)

(September 13, 2017)

References

[change|change source]- ↑1.01.11.21.3"Cassini–Huygens: Quick Facts".NASA.RetrievedAugust 20,2011.

- ↑Krebs, Gunter Dirk."Cassini / Huygens".Gunter's Space Page.RetrievedJune 15,2016.

- ↑Barber, Todd J. (August 23, 2010)."Insider's Cassini: Power, Propulsion, and Andrew Ging".NASA. Archived fromthe originalon April 2, 2012.RetrievedAugust 20,2011.

- ↑"Cassini Post-End of Mission News Conference" (Interview). Pasadena, CA: NASA Television. September 15, 2017.

- ↑"Outer Planets Flagship - Science Mission Directorate".NASA. Archived fromthe originalon May 13, 2017.RetrievedJuly 12,2017.

- ↑Corum, Jonathan (December 18, 2015)."Mapping Saturn's Moons".The New York Times.RetrievedDecember 18,2015.

- ↑"Cassini's First Dive Between Saturn and its Rings".Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

- ↑8.08.18.2"Overview | Cassini".Solar System Exploration: NASA Science.RetrievedJanuary 25,2019.

- ↑"ESA Science & Technology - Cassini Equinox Mission".sci.esa.int.Retrieved2022-08-22.

- ↑"Cassini-Huygens".Agenzia Spaziale Italiana. December 2008. Archived fromthe originalon September 21, 2017.RetrievedApril 16,2017.

- ↑Miller, Edward A.; Klein, Gail; Juergens, David W.; Mehaffey, Kenneth; Oseas, Jeffrey M.; et al. (October 1996)."The Visual and Infrared Mapping Spectrometer for Cassini"(PDF).In Horn, Linda (ed.).Cassini/Huygens: A Mission to the Saturnian Systems.Vol. 2803. pp. 206–220.Bibcode:1996SPIE.2803..206M.doi:10.1117/12.253421.S2CID34965357.Archived fromthe original(PDF)on August 9, 2017.RetrievedAugust 14,2017.

- ↑Reininger, Francis M.; Dami, Michele; Paolinetti, Riccardo; Pieri, Silvano; Falugiani, Silvio; et al. (June 1994). "Visible Infrared Mapping Spectrometer--visible channel (VIMS-V)". In Crawford, David L.; Craine, Eric R. (eds.).Instrumentation in Astronomy VIII.Vol. 2198. pp. 239–250.Bibcode:1994SPIE.2198..239R.doi:10.1117/12.176753.S2CID128716661.

- ↑Brown, Dwayne; Martinez, Carolina (April 15, 2008)."NASA Extends Cassini's Grand Tour of Saturn".NASA / Jet Propulsion Laboratory.RetrievedAugust 14,2017.

- ↑"Mission Summary".sci.esa.int.RetrievedFebruary 3,2017.

- ↑"New Cassini Images of Asteroid Available"(Press release). JPL. February 11, 2000. Archived fromthe originalon June 12, 2010.RetrievedOctober 15,2010.

- ↑Dumé, Isabelle (24 September 2003)."General relativity passes Cassini test".Physics World.

- ↑Meltzer 2015, pp. 346–351

- ↑"Newest Saturn moons given names".BBC News.February 28, 2005.RetrievedSeptember 1,2016.

- ↑Spitale, J. N.; Jacobson, R. A.; Porco, C. C.; Owen, W. M. Jr. (2006)."The orbits of Saturn's small satellites derived from combined historic andCassiniimaging observations ".The Astronomical Journal.132(2): 692–710.Bibcode:2006AJ....132..692S.doi:10.1086/505206.

- ↑"Surprise! Saturn has small moon hidden in ring".NBC News.March 3, 2009. Archived fromthe originalon December 17, 2013.RetrievedAugust 29,2015.

- ↑Green, Daniel W. E. (November 2, 2009)."IAU Circular No. 9091".CICLOPS. Archived fromthe originalon June 11, 2011.RetrievedAugust 20,2011.

- ↑Platt, Jane; Brown, Dwayne (April 14, 2014)."NASA Cassini Images May Reveal Birth of a Saturn Moon".NASA.RetrievedApril 14,2014.

- ↑Porco, C. C.; Baker, E.; Barbara, J.; Beurle, K.; Brahic, A.; Burns, J. A.; Charnoz, S.; Cooper, N.; Dawson D., D.; Del Genio, A. D.; Denk, T.; Dones, L.; Dyudina, U.; Evans, M. W.; Giese, B.; Grazier, K.; Heifenstein, P.; Ingersoll, A. P.; Jacobson, R. A.; Johnson, T. V.; McEwen, A.; Murray, C. D.; Neukum, G.; Owen, W. M.; Perry, J.; Roatsch, T.; Spitale, J.; Squyres, S.; Thomas, P. C.; Tiscareno, M.; Turtle, E.; Vasavada, A. R.; Veverka, J.; Wagner, R.; West, R. (2005)."Cassini Imaging Science: Initial results on Phoebe and Iapetus"(PDF).Science.307(5713): 1237–1242.Bibcode:2005Sci...307.1237P.doi:10.1126/science.1107981.PMID15731440.S2CID20749556.

- ↑"HUYGENS: THE TOP 10 DISCOVERIES AT TITAN".European Space Agency.Retrieved9 July2024.

- ↑Tomasko, M. G.; Archinal, B.; Becker, T.; Bézard, B.; Bushroe, M.; Combes, M.; Cook, D.; Coustenis, A.; De Bergh, C.; Dafoe, L. E.; Doose, L.; Douté, S.; Eibl, A.; Engel, S.; Gliem, F.; Grieger, B.; Holso, K.; Howington-Kraus, E.; Karkoschka, E.; Keller, H. U.; Kirk, R.; Kramm, R.; Küppers, M.; Lanagan, P.; Lellouch, E.; Lemmon, M.; Lunine, Jonathan I.; McFarlane, E.; Moores, J.; et al. (2005). "Rain, winds and haze during the Huygens probe's descent to Titan's surface".Nature.438(7069): 765–778.Bibcode:2005Natur.438..765T.doi:10.1038/nature04126.PMID16319829.S2CID4414457.

- ↑Cook, Jia-Rui; Brown, Dyawne C. (July 6, 2011)."Cassini Spacecraft Captures Images and Sounds of Big Saturn Storm".JPL. Archived fromthe originalon March 3, 2008.RetrievedAugust 20,2011.

- ↑"CassiniSpacecraft to Dive Into Water Plume of Saturn Moon ".ArchivedNovember 9, 2020, at theWayback Machine

- ↑"CassiniTastes Organic Material at Saturn's Geyser Moon ".ArchivedJuly 20, 2021, at theWayback Machine.NASA, March 26, 2008

- ↑"Cassini Sends Back Images of Enceladus as Winter Nears".Archived fromthe originalon March 11, 2016.RetrievedDecember 13,2018.

- ↑Amos, Jonathan (April 3, 2014)."Saturn's Enceladus moon hides 'great lake' of water".BBC News.RetrievedApril 7,2014.

- ↑Iess, L.; Stevenson, D. J.; Parisi, M.; Hemingway, D.; Jacobson, R. A.; Lunine, Jonathan I.; Nimmo, F.; Armstrong, J. W.; Asmar, S. W.; Ducci, M.; Tortora, P. (April 4, 2014)."The Gravity Field and Interior Structure of Enceladus"(PDF).Science.344(6179): 78–80.Bibcode:2014Sci...344...78I.doi:10.1126/science.1250551.PMID24700854.S2CID28990283.

- ↑Sample, Ian (April 3, 2014)."Ocean discovered on Enceladus may be best place to look for alien life".The Guardian.RetrievedApril 3,2014.

- ↑Dyches, Preston; Clavin, Whitney (June 25, 2014)."Cassini Celebrates 10 Years Exploring Saturn".NASA.RetrievedJune 25,2014.

- ↑"Cassini Finds Global Ocean in Saturn's Moon Enceladus".Jet Propulsion Laboratory.RetrievedSeptember 14,2015.

- ↑"Deepest-Ever Dive Through Enceladus Plume Completed".Jet Propulsion Laboratory. October 28, 2015.RetrievedOctober 29,2015.

- ↑Chang, Kenneth (14 December 2023)."Poison Gas Hints at Potential for Life on an Ocean Moon of Saturn".The New York Times.Archivedfrom the original on 14 December 2023.Retrieved15 December2023.

A researcher who has studied the icy world said 'the prospects for the development of life are getting better and better on Enceladus'.

- ↑Peter, Jonah S.; et al. (14 December 2023)."Detection of HCN and diverse redox chemistry in the plume of Enceladus".Nature Astronomy.8(2): 164–173.arXiv:2301.05259.doi:10.1038/s41550-023-02160-0.S2CID255825649.Archivedfrom the original on 15 December 2023.Retrieved15 December2023.

- ↑"Catalog Page for PIA05380: Approach to Saturn".NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory. February 26, 2004.RetrievedAugust 20,2011.

- ↑"The Rings of Saturn".Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Tennessee in Knoxville. Archived fromthe originalon December 12, 2013.RetrievedDecember 5,2013.

- ↑"Cassini Spacecraft Captures Images and Sounds of Big Saturn Storm".JPL. July 6, 2011. Archived fromthe originalon April 30, 2008.RetrievedAugust 20,2011.

- ↑"Cassini-Huygens: News".JPL. Archived fromthe originalon May 8, 2008.RetrievedAugust 20,2011.

- ↑"Huge 'hurricane' rages on Saturn".BBC News.November 10, 2006.RetrievedNovember 10,2006.

- ↑"Cassini Probe Flies by Iapetus, Goes into Safe Mode".Fox News.September 14, 2007. Archived fromthe originalon October 21, 2012.RetrievedSeptember 17,2007.

- ↑"Cassini's Tour of the Saturn System".Planetary Society.Archived fromthe originalon April 25, 2009.RetrievedFebruary 26,2009.

- ↑"Cassini To Earth: 'Mission Accomplished, But New Questions Await!'".Science Daily.June 29, 2008.RetrievedJanuary 5,2009.

- ↑John Spencer (February 24, 2009)."Cassini's proposed extended-extended mission tour".Planetary Society. Archived fromthe originalon June 15, 2010.RetrievedAugust 20,2011.

- ↑"NASA Extends Cassini's Tour of Saturn, Continuing International Cooperation for World Class Science".ArchivedApril 13, 2016, at theWayback Machine

- ↑Brown, Dwayne; Zubritsky, Elizabeth; Neal-Jones, Nancy; Cook, Jia-Rui (25 October 2012)."NASA Spacecraft Sees Huge Burp At Saturn After Large Storm".NASA.NASA.Archivedfrom the original on October 27, 2012.Retrieved14 April2021.

- ↑Cook, Jia-Rui (20 December 2012)."Cassini Instrument Learns New Tricks".Jet Propulsion Laboratory,NASA.Archivedfrom the original on December 22, 2012.Retrieved14 April2021.

- ↑"Cassini probe takes image of Earth from Saturn orbit".BBC News.July 23, 2013.RetrievedJuly 24,2013.

- ↑Overbye, Dennis (November 12, 2013)."The View From Saturn".The New York Times.RetrievedNovember 12,2013.

- ↑"Smile! Cassini sets up photo of Earth".BBC News.July 19, 2013.RetrievedJuly 24,2013.

- ↑"Saturn Tour Dates: 2015".NASA / Jet Propulsion Laboratory. 2015. Archived fromthe originalon May 18, 2015.RetrievedMay 2,2017.

- ↑"Return to Rhea (NASA Cassini Saturn Mission Images)".Cassini Imaging Central Laboratory for Operations. March 30, 2015. PIA19057. Archived fromthe originalon June 21, 2017.RetrievedMay 11,2015.

- ↑"Cassini Prepares for Last Up-close Look at Hyperion".NASA / Jet Propulsion Laboratory.May 28, 2015.RetrievedMay 29,2015.

- ↑"Cassini to Make Last Close Flyby of Saturn Moon Dione".NASA / Jet Propulsion Laboratory.August 13, 2015. Archived fromthe originalon August 15, 2015.RetrievedAugust 20,2015.

- ↑"Changing Colors in Saturn's North".Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

- ↑Spencer, John (February 24, 2009)."Cassini's Proposed Extended-Extended Mission Tour".The Planetary Society.

- ↑"Cassini Post-End of Mission News Conference" (Interview). Pasadena, CA: NASA Television. September 15, 2017.

- ↑Overbye, Dennis(September 8, 2017)."Cassini Flies Toward a Fiery Death on Saturn".The New York Times.RetrievedSeptember 10,2017.

- ↑Spilker, Linda."Cassini Extended Missions"(PDF).RetrievedAugust 20,2011.

- ↑Blabber, Phillipa; Verrecchia, Angélique (April 3, 2014)."Cassini-Huygens: Preventing Biological Contamination".Space Safety Magazine.RetrievedAugust 1,2015.

- ↑Lakdawalla, Emily (3 September 2014)."Cassini's awesomeness fully funded through mission's dramatic end in 2017".The Planetary Society.Archivedfrom the original on August 10, 2020.Retrieved14 April2021.

- ↑"2016 Saturn Tour Highlights".

- ↑Lewin, Sarah."Cassini Mission Kicks Off Finale at Saturn".Scientific American.RetrievedNovember 30,2016.

- ↑Dyches, Preston; Brown, Dwayne; Cantillo, Laurie (April 27, 2017)."NASA Spacecraft Dives Between Saturn and Its Rings".NASA / Jet Propulsion Laboratory.RetrievedMay 2,2017.

- ↑McGregor, Veronica; Brown, Dwight; Wendel, JoAnna (September 10, 2018)."And the Emmy goes to: Cassini's Grand Finale".NASA.RetrievedSeptember 10,2018.

- ↑Loff, Sarah (September 15, 2017)."Impact Site: Cassini's Final Image".NASA.RetrievedSeptember 17,2017.

Other websites

[change|change source]- Spacecraft Cassini is Visiting Saturn!— children's stories explaining the Cassini mission

- Cassini-Huygens Main PageArchived2012-12-27 at theWayback MachineatNASA

- Cassini Mission HomepageArchived2006-04-28 at theWayback Machineby the Jet Propulsion Laboratory

- Cassini-Huygens Mission ProfileArchived2013-12-16 at theWayback Machineby NASA's Solar System Exploration

- Cassini Imaging Homepage

- Cassini informationby the National Space Science Data Center (NSSDC).

- Photo Gallery - full coverage

- Cassini's Tour de Saturn part A,B,C,D,E,F– descriptions of the 4-year tour of Saturn by Bruce Moomaw

- SpaceflightNow news coverage of the missionArchived2013-02-03 at theWayback Machine

- Countdown to Cancel the Cassini Space Probeby the Baltimore Peace Network in 1997 due to concerns over the use of plutonium