Plate tectonics

Plate tectonicsis atheoryofgeology.It explains movement of theEarth'slithosphere.The lithosphere is theEarth's crustand the upper part of themantle.The lithosphere is divided into plates, some of which are very large and can be entirecontinents.

Heat from themantleis the source of energy driving plate tectonics. Exactly how this works is still a matter of debate. This theory includes the idea ofcontinental drift.[1]

Earth's crust[change|change source]

The outermost part of thestructure of the Earthis made up of two layers. The lithosphere, above, is solid. It includes thecrustand the uppermost part of the mantle.

Below the lithosphere is theasthenosphere.The asthenosphere is like a solid or a hotviscousliquid. It can flow like a liquid on long time scales. Largeconvectioncurrents in the asthenosphere transfer heat to the surface, where plumes of less densemagmabreak apart the plates at the spreading centers. The deeper mantle below the asthenosphere is more rigid again. This is caused by extremely high pressure.

Continental and oceanic plates[change|change source]

There are two types of tectonic plates: oceanic and continental.

Anoceanicplate is a tectonic plate at the bottom of the oceans. It is primarily made ofmaficrocks, rich inironandmagnesium.It is thinner than the continental crust (generally less than 10 kilometers thick) anddenser.It is also younger than continental crust. When they collide, the oceanic plate moves underneath the continental plate because of its density. As a result, it melts in the mantle and reforms. The oldest oceanic rocks are less than 200 million years old.

Continental plate is the thick part of the earth's crust which forms the large land masses. Continental rock has lowerdensitythan oceanic rock. They are mostly made offelsicrocks. These havegranite,with its abundantsilica,aluminum,sodiumandpotassium.Continental plates are rarely destroyed. Their oldest rocks seem to be 4billionyears old. Oceanic plates cover about 71 percent of Earth’s surface, while continental plates cover 29 percent.

Thickness of plates[change|change source]

Ocean lithosphere varies in thickness. Because it is formed atmid-ocean ridgesand spreads outward, it gets thicker as it moves further away from the mid-ocean ridge. Typically, the thickness varies from about 6 kilometres (3.7 mi) thick at mid-ocean ridges to greater than 100 kilometres (62 mi) atsubductionzones.[1]

Continental lithosphere is about 200 kilometres (120 mi) thick. It varies between basins, mountain ranges, and the stablecratonicinteriors of continents. The two types of crust differ in thickness, with continental crust being much thicker than oceanic: 35 kilometres (22 mi) vs. 6 kilometres (3.7 mi).[1]

Movement of plates[change|change source]

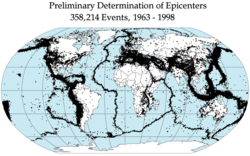

The lithosphere consists oftectonic plates.There are seven major and many minor plates. The lithospheric plates ride on theasthenosphere(aesthenosphere). The plate boundary is where two plates meet. When movement occurs, the plates may createmountains,earthquakes,volcanoes,mid-oceanic ridgesand oceanic trenches, depending on which way the plates are moving.[3][4][5][6][7]

- Convergent boundaries:two plates move toward each other. Sometimes one plate will move under the other. This is calledsubduction.When an oceanic plate collides with a continental plate, the oceanic plate will move underneath the continental because it is denser. Convergent boundaries can create mountains and volcanoes. TheAndesmountain range inSouth Americaand theJapaneseislandarcare examples, along with thePacific Ring of Fire.

- Divergent boundaries:two plates move apart. As shown in the diagram, the place where the boundary occurs is called a rift. Magma from the mantle pushes up and cools off forming new land. They create earthquakes and trenches. TheMid-ocean ridgesandAfrica'sGreat Rift Valleyare examples.

- Transform fault boundaries:two plates move side to side. They make earthquakes. TheSan Andreas FaultinCaliforniais an example of a transform boundary.New Zealandis another, more complex, example.

Earthquakes,volcanic activity,mountain-building, andoceanic trenchformation occur along plate boundaries. The lateral movement of the plates varies from:

- 1–4 centimetres (0.39–1.57 in) per year (Mid-Atlantic Ridge). This is as fast as fingernails grow.

- 10 centimetres (3.9 in) per year (Nazca Plate). This is as fast as hair grows.[8][9]

Major plates[change|change source]

Depending on how they are defined, seven or eight major plates are usually listed:

- African plate

- Antarctic plate

- Indo-Australian plate,sometimes subdivided into:

- Eurasian plate

- North American plate

- South American plate

- Pacific plate

Related pages[change|change source]

References[change|change source]

- ↑1.01.11.2Turcotte, D.L.; Schubert, G. (2002). "Plate Tectonics".Geodynamics(2 ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp.1–21.ISBN0-521-66186-2.

- ↑Merdith, Andrew (16 December 2020)."Plate tectonics, Rodinia, Gondwana, supercontinent cycle".Plate model for 'Extending Full-Plate Tectonic Models into Deep Time: Linking the Neoproterozoic and the Phanerozoic'.doi:10.5281/zenodo.4485738.Retrieved23 September2022.

- ↑Rolf Meissner 2002.The little book of planet Earth.New York: Copernicus Books. p202ISBN978-0-387-95258-1.

- ↑"Plate Tectonics: Plate boundaries".platetectonics.com. Archived fromthe originalon 16 June 2010.Retrieved12 June2010.

- ↑Tackley, Paul J. (2000-06-16). "Mantle convection and plate tectonics: towards an integrated physical and chemical theory".Science.288(5473): 2002–2007.Bibcode:2000Sci...288.2002T.doi:10.1126/science.288.5473.2002.PMID10856206.

- ↑Seyfert, Carl K. (1987).The encyclopedia of structural geology and plate tectonics.ISBN9780442281250.

- ↑Oreskes, Naomi ed. 2003.Plate tectonics: an insider's history of the modern theory of the Earth.Westview PressISBN0-8133-4132-9

- ↑Huang Zhen Shao (1997)."Speed of the continental plates".The physics factbook.

- ↑Hancock, Paul L; Skinner, Brian J; Dineley, David L (2000).The Oxford Companion to the Earth.Oxford University Press.ISBN0198540396.

- McKnight, Tom 2004.Geographica: the complete illustrated atlas of the world,Barnes and Noble; New York.ISBN0-7607-5974-X

- Stanley, Steven M. 1999.Earth system history.Freeman, p211–228.ISBN0-7167-2882-6

- Thompson, Graham R. & Turk, Jonathan 1991.Modern physical geology.Saunders.ISBN0-03-025398-5

- Turcotte D.L. & Schubert G. 2002.Geodynamics.2nd ed, Wiley, New York.ISBN0-521-66624-4

Other websites[change|change source]

- Movieshowing 750 million years of global tectonic activity.

- More moviesover smaller regions and smaller time scales.

- Easy-to-draw illustrations for teaching plate tectonics

- Map of tectonic platesArchived2017-01-12 at theWayback Machine

- Plate tectonics-Citizendium