Yellow journalism

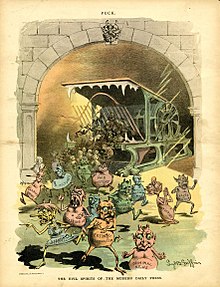

Yellow journalismor theyellow pressis a type ofjournalismthat does not report much real news withfacts.It uses shockingheadlinesthat catch people's attention to sell morenewspapers.Yellow journalism might includeexaggeratingfacts or spreadingrumors.

Yellow press newspapers have several columns and front-page headlines about different types of news, such assportsandscandals.They use bold layouts (with large illustrations and perhaps color), and stories reported using unnamed sources. The term was often used to talk about some largeNew York Citynewspapers around 1900 as they fought to get more readers than the other newspapers.[1]

In 1941, Frank Mott said that there were five things that made up yellow journalism:[2]

- headlines in huge print that were meant to scare people, often of news that wasn't very important

- using many pictures or drawings

- using fakeinterviews,headlines that didn't tell the whole truth,pseudoscience(fake science), and false information from people who said they were experts

- full-color parts of the newspaper on Sundays, usually withcomic strips(which is now normal in theUnited States)

- taking the side of the "underdog" against the system.

Origins: Pulitzer vs. Hearst

[change|change source]

The term came from theAmericanGilded Ageof the 1890s when new technology made newspapers cheaper. Two newspaper owners in New York fought to get more readers and sell more newspapers than the other. These wereJoseph Pulitzerwith theNew York WorldandWilliam Randolph Hearstwith theNew York Journal.The most important part of this fight was from 1895 to about 1898. When people talk about "yellow journalism" in history, they are often talking about these years.

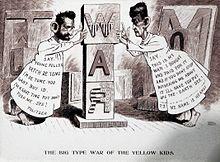

Both papers were accused of sensationalizing the news (making it seem much more important than it really was) in order to sell more newspapers, although they did serious reporting as well. TheNew York Pressused the term "Yellow Kidjournalism "in early 1897 after a then-popular comic strip, to talk about the newspapers of Pulitzer and Hearst, which both published versions of it during a circulation war.[3]Ervin Wardman, publisher of theNew York Herald(which was not "yellow journalism" ) invented it.[4]

Joseph Pulitzerbought theNew York Worldin 1883 after making theSt. Louis Post-Dispatchthe biggest daily newspaper in that city. Pulitzer tried to make theNew York Worldfun to read, and filled his paper with pictures, games and contests that brought in new readers. Crime stories filled many of the pages, with headlines like "Was He a Suicide?" and "Screaming for Mercy."[5]Also, Pulitzer only charged readers two cents per issue but gave readers eight and sometimes 12 pages of information (the only other two cent paper in the city was never longer than four pages).[6]

While there were many sensational stories in theNew York World,they were by no means the only stories, or even the biggest ones. Pulitzer believed that newspapers were important and had a duty to make society better, and he tried to do this with his newspaper.

Just two years after Pulitzer took it over, theWorldsold more copies than any other newspaper in New York. Part of this was because he was connected to theDemocratic Party.[7]Older publishers, who were jealous of Pulitzer's success, began saying bad things about theWorld.They talked about how he had crime stories and stunts but ignored its more serious reporting. Charles Anderson Dana|Charles Dana, editor of theNew York Sun,attackedThe Worldand said Pulitzer was "deficient in judgment and in staying power."[8]

William Randolph Hearst,a mining heir who bought theSan Francisco Examinerfrom his father in 1887, noticed what Pulitzer was doing. Hearst read theWorldwhile studying atHarvard University.He decided to try to make theExamineras bright as Pulitzer's paper.[9]While he was in charge, theExaminergave 24 percent of its space to crime, presenting the stories asmorality plays,and putadulteryand "nudity" (by 19th century standards) on the front page.[10]A month after Hearst took over the paper, theExaminerran this headline about a hotel fire:

HUNGRY, FRANTIC FLAMES. They Leap Madly Upon the Splendid Pleasure Palace by the Bay of Monterey, Encircling Del Monte in Their Ravenous Embrace From Pinnacle to Foundation. Leaping Higher, Higher, Higher, With Desperate Desire. Running Madly Riotous Through Cornice, Archway and Facade. Rushing in Upon the Trembling Guests with Savage Fury. Appalled and Panic-Striken the Breathless Fugitives Gaze Upon the Scene of Terror. The Magnificent Hotel and Its Rich Adornments Now a Smoldering heap of Ashes. TheExaminerSends a Special Train to Monterey to Gather Full Details of the Terrible Disaster. Arrival of the Unfortunate Victims on the Morning's Train — A History of Hotel del Monte — The Plans for Rebuilding the Celebrated Hostelry — Particulars and Supposed Origin of the Fire.[11]

Hearst could beover the topin his crime coverage. One of his early stories, about a "band of murderers", attacked the police for forcingExaminerreporters to do their work for them. But while doing these things, theExamineralso increased its space for international news, and sent reporters out to uncover corruption andinefficiencyin the city government. In one story,ExaminerreporterWinifred Blackwent into a San Francisco hospital as a patient and discovered that the women there were treated with "gross cruelty". The entire hospital staff was fired the morning the story was printed.[12]

New York

[change|change source]With theExaminer'having success by the early 1890s, Hearst began looking for a New York newspaper to buy, and bought theNew York Journalin 1895, a newspaper that sold for one penny which Pulitzer's brother Albert had sold to a Cincinnati publisher the year before.

After noticing what Pulitzer had done by keeping his newspaper at two cents, Hearst made theJournal'sonly cost one cent, while providing as much information as rival newspapers.[6]This worked, and as theJournal'shad 150,000 people subscribe to it, Pulitzer cut his price to a penny, hoping to make Hearst (who was subsidized by his family's fortune) run out of money. Hearst then hired many people who were working forWorldin 1896. While most sources say that Hearst simply offered more money, Pulitzer — who had grown more abusive to his employees — had become a very difficult man to work for, and manyWorldemployees were willing to switch newspapers just to get away from him.[13]

Although the competition between theWorldand theJournalwas fierce, the newspapers had a lot in common. Both wereDemocratic,both took the side oforganized laborandimmigrants(unlike publishers like theNew York Tribune'sWhitelaw Reid,who blamed theirpovertyon moral defects[8]), and both spent a lot of money making their Sunday publications, which were like weekly magazines, going beyond just daily journalism.[14]

Their Sunday entertainment features included the first colorcomic strippages, and some think that the term yellow journalism originated there, while as noted above, theNew York Pressleft the term it invented undefined.Hogan's Alley,a comic strip about a bald child in a yellow nightshirt (nicknamed TheYellow Kid), became very popular when cartoonist Richard F. Outcault began drawing it in theWorldin early 1896. When Hearst hired Outcault away, Pulitzer asked artist George Luks to continue drawing the strip with his characters, giving the city two Yellow Kids.[15]The use of "yellow journalism" as a term for over-the-top sensationalism in the U.S. apparently started with more serious newspapers commenting how far "the Yellow Kid papers" went.

Spanish-American War

[change|change source]Pulitzer and Hearst are often credited (or blamed) for drawing the nation into theSpanish-American Warwith their sensationalism. However, most of Americans did not live in New York City, and the decision makers who did live there probably read less sensationalist newspapers like theTimes,The Sunor thePost.The most famous example of the exaggeration is the story, which probably is not actually true, that artist Frederic Remington sent Hearst atelegramto tell him that not much was going on inCubaand "There will be no war." Hearst responded "Please remain. You furnish the pictures and I'll furnish the war." The story (a version of which appears in the Hearst-inspiredOrson WellesfilmCitizen Kane) first showed up in thememoirsof reporter James Creelman in 1901, and there is no other source for it.

But Hearst did want the United States to go to war after a rebellion broke out in Cuba in 1895. Stories about Cubans being good people and Spain treating Cuba badly soon showed up on his front page. While the stories were probably not veryaccurate,the newspaper readers of the 19th century did not expect, or necessarily want, his stories to be pure nonfiction. Historian Michael Robertson has said that "Newspaper reporters and readers of the 1890s were much less concerned with distinguishing among fact-based reporting, opinion and literature."[16]

Pulitzer, although he did not have Hearst's resources, kept the story on his front page. The yellow press published a lot about the revolution (much of which was not quite true), but conditions on Cuba were bad enough. The island was in a bad economic depression, and Spanish general Valeriano Weyler, sent to crush the rebellion, herded Cuban peasants intoconcentration campsleading hundreds of Cubans to their deaths. Having fought for a fight for two years, Hearst took credit for the conflict when it came: A week after the United States declared war on Spain, he ran "How do you like theJournal'swar? "on his front page.[17]In fact, PresidentWilliam McKinleynever read theJournal,and newspapers like theTribuneand theNew York Evening Post.Also, journalism historians have noted that yellow journalism mostly only happened inNew York City,and that newspapers in the rest of the country did not do it. TheJournaland theWorldwere not among the top ten sources of news in regional papers, and their stories did not catch people's attention outside New York City.[18]

Hearst sailed to Cuba, when the invasion began, as a war correspondent, providing sober and accurate accounts of the fighting.[19]Creelman later praised the work of the reporters for writing about how Spain treated Cuba, arguing, "no true history of the war... can be written without an acknowledgment that whatever of justice and freedom and progress was accomplished by the Spanish-American war was due to the enterprise and tenacity ofyellow journalists,many of whom lie in unremembered graves. "[18]

After the war

[change|change source]Hearst was a well-known Democrat who promotedWilliam Jennings Bryanfor president in 1896 and 1900 (Bryan did not win either election). He later ran for mayor and governor and even tried to get nominated for president, but his reputation was hurt in 1901 after columnistAmbrose Bierceand editorArthur Brisbanepublished separate columns months apart that suggested that PresidentWilliam McKinleybe assassinated. When McKinley was shot on September 6, 1901, critics accused Hearst's Yellow Journalism of drivingLeon Czolgoszto the deed. Hearst did not know of Bierce's column and claimed to have pulled Brisbane's after it ran in a first edition, but the incident would haunt him for the rest of his life and all but destroyed his dream to be president.[20]

Pulitzer, haunted by what had happened, "[21]returned theWorldto its crusading roots in the new century. By the time of his death in 1911, theWorldwas a widely-respected publication, and would remain a leading progressive paper until its demise in 1931.

Related pages

[change|change source]Notes

[change|change source]- ↑Campbell (2001)

- ↑Frank Luther Mott 1041.American Journalism,p. 539.online

- ↑Wood 2004

- ↑W. Joseph Campbell 2009.Yellow Journalism: puncturing the myths, defining the legacies.pp. 37-38 online

- ↑Swanberg 1967,pp. 74–75

- ↑6.06.1Nasaw 2000,p. 100

- ↑Swanberg 1967,p. 91

- ↑8.08.1Swanberg 1967,p. 79

- ↑Nasaw 2000,pp. 54–63

- ↑Nasaw 2000,pp. 75–77

- ↑Nasaw 2000,p. 75

- ↑Nasaw 2000,pp. 69–77

- ↑Nasaw 2000,p. 105

- ↑Nasaw 2000,p. 107

- ↑Nasaw 2000,p. 108

- ↑Nasaw 2000,quoted on p. 79

- ↑Nasaw 2000,p. 132

- ↑18.018.1Smythe 2003,p. 191

- ↑Nasaw 2000,p. 138

- ↑Nasaw 2000,pp. 156–158

- ↑Emory & Emory 1984,p. 295

References

[change|change source]- Auxier, George W. (March 1940),"Middle Western Newspapers and the Spanish American War, 1895–1898",Mississippi Valley Historical Review,vol. 26, no. 4, Organization of American Historians, pp. 523–534,doi:10.2307/1896320,JSTOR1896320

- Campbell, W. Joseph (2005),The Spanish-American War: American Wars and the Media in Primary Documents,Greenwood Press

- Campbell, W. Joseph (2001),Yellow Journalism: Puncturing the Myths, Defining the Legacies,Praeger

- Emory, Edwin; Emory, Michael (1984),The Press and America(4th ed.),Prentice Hall

- Milton, Joyce (1989),The Yellow Kids: Foreign correspondents in the heyday of yellow journalism,Harper & Row

- Nasaw, David (2000),The Chief: The Life of William Randolph Hearst,Houghton Mifflin

- Procter, Ben (1998),William Randolph Hearst: The Early Years, 1863–1910,Oxford University Press,archived fromthe originalon 2011-08-17,retrieved2017-08-31

- Rosenberg, Morton; Ruff, Thomas P. (1976),Indiana and the Coming of the Spanish-American War,Ball State Monograph, No. 26, Publications in History, No. 4, Muncie, IN: Ball State University(Asserts that Indiana papers were "more moderate, more cautious, less imperialistic and less jingoistic than their eastern counterparts." )

- Smythe, Ted Curtis (2003), Sloan, W. David; Startt, James D. (eds.),The Gilded Age Press, 1865–1900,The History of American Journalism, Number 4, Westport, CT: Praeger, archived fromthe originalon 2012-07-16,retrieved2017-08-31

- Swanberg, W.A (1967),Pulitzer,Charles Scribner's Sons

- Sylvester, Harold J. (February 1969), "The Kansas Press and the Coming of the Spanish-American War",The Historian,31(Sylvester finds no Yellow journalism influence on the newspapers in Kansas.)

- Welter, Mark M. (Winter 1970), "The 1895–1898 Cuban Crisis in Minnesota Newspapers: Testing the 'Yellow Journalism' Theory",Journalism Quarterly,vol. 47, pp. 719–724

- Winchester, Mark D. (1995), "Hully Gee, It's a WAR! The Yellow Kid and the Coining of Yellow Journalism",Inks: Cartoon and Comic Art Studies,vol. 2, no. 3, pp. 22–37

- Wood, Mary (February 2, 2004),"Selling the Kid: The Role of Yellow Journalism",The Yellow Kid on the Paper Stage: Acting out Class Tensions and Racial Divisions in the New Urban Environment,American Studies at theUniversity of Virginia,archived fromthe originalon November 7, 2014,retrievedDecember 1,2010

Other websites

[change|change source]- Campbell, W. Joseph (Summer 2000),"Not likely sent: The Remington-Hearst 'telegrams'",Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly,retrieved2008-09-06

- (in French)Charte de Munich (1971) Déclaration des devoirs et des droits des journalistes