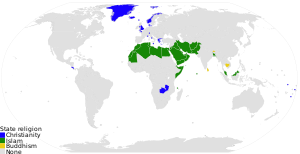

Devlet dini

| Siyaset serisininbir parçası |

| Hükûmetbiçimleri |

|---|

| Hükûmet biçimleri listesi |

Devlet diniya daresmî din,devlet tarafından onaylanan ve desteklenen birdinîyapı ya daakide.Resmî dini olan bir devlet,sekülerolmamasına karşın mutlakateokratikolmak zorunda da değildir.

Hristiyan ülkelerdedevlet kilisesiRoma İmparatorluğu'nun devlet kilisesi ile ilişkilidir ancak aynı zamanda Hristiyanlığın modern süreçte yaşadığı bir evrime denk gelir ve dinin ulusal bir kolu gibi kabul edilir. Devlet dini her zaman devlet tarafından kabul edilmiş bir din anlamına gelse de, her zaman devletin bir din tarafından kontrol ediliyor olduğu (yani teokrasi) ya da dinin devlet tarafından kontrol ediliyor olduğu anlamına gelmez.

Devletler tarafından finanse edilen dinsel kültler oldukça eski dönemlere,Antik Yakın Doğu'ya hatta tarih öncesi dönemlere kadar gider. Dinî kültlerle devlet ilişkisiMarcus Terentius Varrotarafındanpolitik teoloji(theologia civilis) terimi ile tartışılmıştır. Devlet tarafından finanse edilen ilk "devlet kilisesi" MS 301'de kurulanErmeni Apostolik Kilisesi'dir.

Devlet dini olan ülkeler[değiştir|kaynağı değiştir]

Budizm[değiştir|kaynağı değiştir]

Budizmindevlet dini olduğu ülkeler:

Özel statüye sahip olan ülkeler:

Hristiyanlık[değiştir|kaynağı değiştir]

Hristiyanlığıresmî din olarak tanıyan ülkeler aşağıda listelenmiştir

Katoliklik[değiştir|kaynağı değiştir]

Katolikliğiresmî din olarak benimsemiş ülkeler:

Özel statüye, desteğe veya tanınmaya sahip, ancak devlet dini olmayan:

Doğu Ortodoks Kilisesi[değiştir|kaynağı değiştir]

Aşağıda yer alan devletlerDoğu Ortodoks Kilisesi'ne özel statü veya tanınma vermekte olup, devlet dinine sahip değillerdir.

Protestanlık[değiştir|kaynağı değiştir]

AşağıdaProtestanlığıhukuken kabul etmiş ülkeler listelenmiştir.

Anglikanizm[değiştir|kaynağı değiştir]

Aşağıdaki ülke ve bağımlı bölgelerdeİngiltere Kilisesiresmî kilisedir:

Kalvinizm[değiştir|kaynağı değiştir]

Aşağıdaki ülkelerKalvinizmiulusal din olarak kabul etmiştir:

Lütercilik[değiştir|kaynağı değiştir]

Lütercilik,aşağıda verilen ülkelerde resmîyete sahiptir:

Metodizm[değiştir|kaynağı değiştir]

Diğer[değiştir|kaynağı değiştir]

Ermenistan:Ermeni Apostolik Kilisesiülkenin ulusal kilisesidir.[42]

Ermenistan:Ermeni Apostolik Kilisesiülkenin ulusal kilisesidir.[42] Dominik Cumhuriyeti:Anayasa devletin dini olmadığını belirtir; buna karşın Vatikan ile yapılmış konkordat Katolikliğin devlet kilisesi olduğunu kabul eder.[43]

Dominik Cumhuriyeti:Anayasa devletin dini olmadığını belirtir; buna karşın Vatikan ile yapılmış konkordat Katolikliğin devlet kilisesi olduğunu kabul eder.[43] Fransa:Fransa'da 1801 yılında Napolyon tarafından devlet dini geri getirildi. Buna karşın bu yasa 1905'te feshedildi ve laiklik benimsendi. Bu dönemdeAlsas-LorenAlman İmparatorluğu kontrolünde bulunmaktaydı. Fransa 1918'de bölgeyi yeniden kontrol altına aldı, ancak bölgedeki bu yerel yasa feshedilmedi. Bu nedenden ötürü bölgedeki yerel yasanın belirlediğiYahudilik,Katoliklik,LütercilikveKalvinizmresmî statüye sahiptir.[44]

Fransa:Fransa'da 1801 yılında Napolyon tarafından devlet dini geri getirildi. Buna karşın bu yasa 1905'te feshedildi ve laiklik benimsendi. Bu dönemdeAlsas-LorenAlman İmparatorluğu kontrolünde bulunmaktaydı. Fransa 1918'de bölgeyi yeniden kontrol altına aldı, ancak bölgedeki bu yerel yasa feshedilmedi. Bu nedenden ötürü bölgedeki yerel yasanın belirlediğiYahudilik,Katoliklik,LütercilikveKalvinizmresmî statüye sahiptir.[44] Haiti1987'den beri Katoliklik resmî din olmasa da, devlet tarafından ayrıcalıklı bir statüde tutulmaktadır.[45][46]

Haiti1987'den beri Katoliklik resmî din olmasa da, devlet tarafından ayrıcalıklı bir statüde tutulmaktadır.[45][46] Macaristan:2011 Macaristan Anayasası din ve devleti ayırmasına rağmen Macaristan'ı "Hristiyan Avrupa'nın içerisinde yer alan" bir devlet olarak tanımlar.[47]

Macaristan:2011 Macaristan Anayasası din ve devleti ayırmasına rağmen Macaristan'ı "Hristiyan Avrupa'nın içerisinde yer alan" bir devlet olarak tanımlar.[47] Portekiz:Ülkede din ve devlet işleri ayrı olup Katolik Kilisesi'ne bazı özel haklar tanınmaktadır.[48]

Portekiz:Ülkede din ve devlet işleri ayrı olup Katolik Kilisesi'ne bazı özel haklar tanınmaktadır.[48] Samoa:2017 yılında bir parlamento oylaması sonucunda Hristiyanlık devlet dini olmuştur.[49][50]

Samoa:2017 yılında bir parlamento oylaması sonucunda Hristiyanlık devlet dini olmuştur.[49][50] Zambiya:1991 Zambiya Anayasası ülkeyi bir "Hristiyan devlet" olarak tanımlar.[51]

Zambiya:1991 Zambiya Anayasası ülkeyi bir "Hristiyan devlet" olarak tanımlar.[51]

Hinduizm[değiştir|kaynağı değiştir]

Hinduizm hiçbir ülkede devlet dini değildir, ancak dünyada bir ülkede özel statüye veya tanınırlığa sahiptir:

Nepal[52](2015'te Hinduizm devlet dini olmaktan çıkarıldı.Proselitizmhalen yasa dışıdır.[53][54])

Nepal[52](2015'te Hinduizm devlet dini olmaktan çıkarıldı.Proselitizmhalen yasa dışıdır.[53][54])

İslam[değiştir|kaynağı değiştir]

Pek çok Müslüman çoğunluğa sahip ülkede İslam devlet dini olarak benimsenmiştir:

Afganistan[55]

Afganistan[55] Cezayir[56]

Cezayir[56] Bangladeş[57][58]

Bangladeş[57][58] Bahreyn[59]

Bahreyn[59] Brunei[60]

Brunei[60] Komorlar[61]

Komorlar[61] Cibuti[62]

Cibuti[62] Mısır[63]

Mısır[63] İran[64]

İran[64] Irak[65]

Irak[65] Ürdün[66]

Ürdün[66] Kuveyt[67]

Kuveyt[67] Libya[68]

Libya[68] Maldivler[69]

Maldivler[69] Malezya[70]

Malezya[70] Moritanya[71]

Moritanya[71] Fas[72]

Fas[72] Umman[73]

Umman[73] Pakistan[74]

Pakistan[74] Filistin[75]

Filistin[75] Katar[76]

Katar[76] Suudi Arabistan[77]

Suudi Arabistan[77] Batı Sahra

Batı Sahra Somali[78]

Somali[78] Birleşik Arap Emirlikleri[79]

Birleşik Arap Emirlikleri[79] Yemen[80]

Yemen[80]

Kaynakça[değiştir|kaynağı değiştir]

- ^"Draft of Tsa Thrim Chhenmo"(PDF).constitution.bt. 1 Ağustos 2007. 27 Kasım 2007 tarihindekaynağından(PDF)arşivlendi.Erişim tarihi:18 Ekim2007.

- Article 3, Spiritual Heritage

- Buddhism is the spiritual heritage of Bhutan, which promotes the principles and values of peace, non-violence, compassion and tolerance.

- TheDruk Gyalpois the protector of all religions in Bhutan.

- It shall be the responsibility of religious institutions and personalities to promote the spiritual heritage of the country while also ensuring that religion remains separate from politics in Bhutan. Religious institutions and personalities shall remain above politics.

- TheDruk Gyalposhall, on the recommendation of the FiveLopons, appoint a learned and respected monk ordained in accordance with theDruk-lu,blessed with the nine qualities of a spiritual master and accomplished inked-dzog,as theJe Khenpo.

- His Holiness theJe Khenposhall, on the recommendation of theDratshang Lhentshog,appoint monks blessed with the nine qualities of a spiritual master and accomplished inked-dzogas the FiveLopons.

- The members of theDratshang Lhentshogshall comprise:

- TheZhung DratshangandRabdeysshall continue to receive adequate funds and other facilities from the State."Bhutan's Constitution of 2008"(PDF).constituteproject.org/.10 Aralık 2017 tarihindekaynağından(PDF)arşivlendi.Erişim tarihi:29 Ekim2017.

- Article 3, Spiritual Heritage

- ^"Constitution of Cambodia".cambodia.org. 26 Eylül 2019 tarihindekaynağındanarşivlendi.Erişim tarihi:13 Nisan2011.(Article 43).

- ^"Lao People's Democratic Republic's Constitution of 1991 with Amendments through 2003"(PDF).constituteproject.org.10 Aralık 2017 tarihindekaynağından(PDF)arşivlendi.Erişim tarihi:29 Ekim2017.

Article 9: The State respects and protects all lawful activities of Buddhists and of followers of other religions, [and] mobilises and encourages Buddhist monks and novices as well as the priests of other religions to participate in activities that are beneficial to the country and people.

- ^"Myanmar's Constitution of 2008"(PDF).constituteproject.org.20 Eylül 2016 tarihindekaynağından(PDF)arşivlendi.Erişim tarihi:29 Ekim2017.

- ^"Arşivlenmiş kopya"(PDF).1 Mart 2020 tarihinde kaynağındanarşivlendi(PDF).Erişim tarihi: 8 Kasım 2020.

- ^Article 67: "The State should support and protect Buddhism and other religions. In supporting and protecting Buddhism, [...] the State should promote and support education and dissemination of dharmic principles of Theravada Buddhism [...], and shall have measures and mechanisms to prevent Buddhism from being undermined in any form. The State should also encourage Buddhists to participate in implementing such measures or mechanisms.""Constitution of the Kingdom of Thailand"(PDF).constitutionnet.org.10 Aralık 2017 tarihindekaynağından(PDF)arşivlendi.Erişim tarihi:29 Ekim2017.

- ^Super User."Costa Rica Constitution in English – Constitutional Law – Costa Rica Legal Topics".costaricalaw.6 Eylül 2015 tarihindekaynağındanarşivlendi.

- ^Constitution Religion,Wayback Machinesitesinde (26 Mart 2009 tarihinde arşivlendi) (archived fromthe originalon 2009-03-26).

- ^"Constitution of Malta (Article 2)".mjha.gov.mt.[ölü/kırık bağlantı]

- ^Constitution de la Principaute,Wayback Machinesitesinde (27 Eylül 2011 tarihinde arşivlendi) (French): Art. 9., Principaute De Monaco: Ministère d'Etat (archived fromthe originalon 2011-09-27).

- ^"Vatican City".Catholic-Pages. 2 Ekim 1999 tarihindekaynağındanarşivlendi.Erişim tarihi: 12 Ağustos 2013.

- ^Temperman, Jeroen (2010).State–Religion Relationships and Human Rights Law: Towards a Right to Religiously Neutral Governance.BRILL.ISBN9789004181496.

... guarantees the Roman Catholic Church free and public exercise of its activities and the preservation of the relations of special co-operation with the state in accordance with the Andorran tradition. The Constitution recognizes the full legal capacity of the bodies of the Roman Catholic Church which have legal status in accordance with their own rules.

- ^*"Argentina's Constitution of 1853, Reinstated in 1983, with Amendments through 1994"(PDF).constituteproject.org.7 Kasım 2017 tarihindekaynağından(PDF)arşivlendi.

- "Argentina – Religión".argentina.gob.ar.8 Ekim 2014 tarihindekaynağındanarşivlendi.

- ^"Constitution of the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste"(PDF).Governo de Timor-Leste. 9 Haziran 2010 tarihindekaynağından(PDF)arşivlendi.

- ^"Google Translate".18 Nisan 2019 tarihindekaynağındanarşivlendi.Erişim tarihi:18 Mart2015.

- ^"Wayback Machine"(PDF).3 Ocak 2015. 3 Ocak 2015 tarihindekaynağından(PDF)arşivlendi.

- ^"Guatemala's Constitution of 1985 with Amendments through 1993"(PDF).Constitution Project.22 Kasım 2015 tarihindekaynağından(PDF)arşivlendi.

The juridical personality of the Catholic Church is recognized. The other churches, cults, entities, and associations of religious character will obtain the recognition of their juridical personality in accordance with the rules of their institution[,] and the Government may not deny it[,] aside from reasons of public order. The State will extend to the Catholic Church, without any cost, [the] titles of ownership of the real assets which it holds peacefully for its own purposes, as long as they have formed part of the patrimony of the Catholic Church in the past. The property assigned to third parties or those

- ^"Constitution of the Italian Republic"(PDF).Senato.it. 22 Kasım 2009 tarihindekaynağından(PDF)arşivlendi.Erişim tarihi:2 Ekim2015.

The State and the Catholic Church are independent and sovereign, each within its own sphere. Their relations are regulated by the Lateran pacts. Amendments to such Pacts which are accepted by both parties shall not require the procedure of constitutional amendments.

- ^Executive Summary – Panama28 Mart 2017 tarihindeWayback Machinesitesindearşivlendi., 2013Report on International Religious Freedom,United States Department of State.

- ^"Constitution of the Republic of Paraguay".15 Ocak 2008 tarihindekaynağındanarşivlendi.

The role played by the Catholic Church in the historical and cultural formation of the Republic is hereby recognized.

- ^"Constitution of the Republic of Peru"(PDF).26 Mayıs 2011 tarihindekaynağından(PDF)arşivlendi.

Within an independent and autonomous system, the State recognizes the Catholic Church as an important element in the historical, cultural, and moral formation of Peru and lends it its cooperation. The State respects other denominations and may establish forms of collaboration with them.

- ^"The Constitution of the Republic of Poland".2 Nisan 1997. 12 Nisan 2003 tarihindekaynağındanarşivlendi.

The relations between the Republic of Poland and the Roman Catholic Church shall be determined by international treaty concluded with the Holy See, and by statute. The relations between the Republic of Poland and other churches and religious organizations shall be determined by statutes adopted pursuant to agreements concluded between their appropriate representatives and the Council of Ministers.

- ^"14, 16 & 27.3".[[Constitution of Spain|Spanish Constitution]](PDF)(Constitution).Erişim tarihi:5 Mart2018.

No religion shall have a state character. The public authorities shall take into account the religious beliefs of Spanish society and shall consequently maintain appropriate cooperation relations with the Catholic Church and other confessions.

Bilinmeyen parametre|articletype=görmezden gelindi (yardım);Birden fazla|başlık=ve|title=kullanıldı (yardım);URL–vikibağı karışıklığı (yardım) - ^Enyedi, Zsolt; Madeley, John T.S. (2 Ağustos 2004).Church and State in Contemporary Europe.Routledge. s. 228.ISBN9781135761417.

Both as a state church and as a national church, the Orthodox Church of Greece has a lot in common with Protestant state churches, and even with Catholicism in some countries.

- ^Meyendorff, John (1981).The Orthodox Church: Its Past and Its Role in the World Today.St Vladimir's Seminary Press. s. 155.ISBN9780913836811.

Greece therefore is today the only country where the Orthodox Church remains a state church and plays a dominant role in the life of the country.

- ^"The Bulgarian Constitution".Parliament of Bulgaria. 10 Aralık 2010 tarihindekaynağındanarşivlendi.Erişim tarihi: 20 Aralık 2011.

- ^"Cyprus's Constitution of 1960 with Amendments through 2013"(PDF).Constitution Project.3 Temmuz 2019 tarihindekaynağından(PDF)arşivlendi.

- ^abFinland – Constitution23 Ocak 2018 tarihindeWayback Machinesitesindearşivlendi., Section 76 The Church Act,http://servat.unibe.ch/icl/fi00000_.html23 Ocak 2018 tarihindeWayback Machinesitesindearşivlendi..

- ^Salla Korpela (Mayıs 2005)."The Church in Finland today".Finland Promotion Board; Produced by the Ministry for Foreign Affairs, Department for Communications and Culture. 10 Eylül 2015 tarihinde kaynağındanarşivlendi.Erişim tarihi: 8 Kasım 2020.

- ^Constitution of Georgia12 Haziran 2018 tarihindeWayback Machinesitesindearşivlendi.Article 9(1&2) and 73(1a1)

- ^"About".Guernsey Deanery.Church of England. 11 Şubat 2017 tarihindekaynağındanarşivlendi.

- ^Gell, Sir James."Gell on Manx Church".Isle of Man Online.IOM Online. 18 Kasım 2002 tarihindekaynağındanarşivlendi.Erişim tarihi: 7 Şubat 2017.

- ^Refugees, United Nations High Commissioner for."Refworld – 2010 Report on International Religious Freedom – Tuvalu".26 Eylül 2013 tarihindekaynağındanarşivlendi.Erişim tarihi: 23 Şubat 2017.

- ^Denmark – Constitution10 Temmuz 2011 tarihindeWayback Machinesitesindearşivlendi.: Section 4 State Church,International Constitutional Law1 Eylül 2019 tarihindeWayback Machinesitesindearşivlendi..

- ^Referenced at the Encyclopedia of Global Religion, edited by Mark Juergensmeyer, published 2012 by Sage publications,978-0-7619-2729-7,page 390. (Page available on-linehere3 Haziran 2019 tarihindeWayback Machinesitesindearşivlendi.).

- ^"Constitution of Denmark – Section IV"(PDF).1 Mart 2016 tarihinde kaynağındanarşivlendi(PDF).Erişim tarihi: 22 Eylül 2016.

The Evangelical Lutheran Church shall be the Established Church of Denmark, and, as such, it shall be supported by the State.

- ^Constitution of the Republic of Iceland4 Temmuz 2013 tarihinde atArchive-Itsitesindearşivlendi:Article 62,Government of Iceland22 Kasım 2017 tarihindeWayback Machinesitesindearşivlendi..

- ^"Norway's Constitution of 1814 with Amendments through 2016"(PDF).Constitution Project.9 Haziran 2020 tarihindekaynağından(PDF)arşivlendi.

- ^"Norway: State and Church Separate After 500 Years".U.S. Library of Congress | Global Legal Monitor.3 Şubat 2017. 9 Şubat 2017 tarihindekaynağındanarşivlendi.

- ^"Sweden's Constitution of 1974 with Amendments through 2012"(PDF).Constitution Project.2 Mayıs 2019 tarihindekaynağından(PDF)arşivlendi.

- ^Ernst, Manfred (1 Nisan 2012)."Changing Christianity in Oceania: a Regional Overview".Archives de sciences sociales des religions(İngilizce) (157): 29-45.doi:10.4000/assr.23613

.ISSN0335-5985.16 Haziran 2018 tarihinde kaynağındanarşivlendi.Erişim tarihi: 8 Kasım 2020.

.ISSN0335-5985.16 Haziran 2018 tarihinde kaynağındanarşivlendi.Erişim tarihi: 8 Kasım 2020.

- ^"National Assembly of the Republic of Armenia".parliament.am.28 Mart 2004 tarihindekaynağındanarşivlendi.

- ^United States Department of State, 2011 Report on International Religious Freedom—Dominican Republic, 30 July 2012, available at:http:// refworld.org/docid/502105c67d.html17 Nisan 2020 tarihindeWayback Machinesitesindearşivlendi.

- ^"Church-state tie opens door for mosque".The New York Times.7 Ekim 2008. 18 Temmuz 2016 tarihinde kaynağındanarşivlendi.Erişim tarihi: 2 Kasım 2013.

- ^"Haiti".State.gov. 14 Eylül 2007. 27 Kasım 2020 tarihinde kaynağındanarşivlendi.Erişim tarihi:4 Ocak2014.

- ^International Religious Freedom Report 2017 Haiti27 Eylül 2020 tarihindeWayback Machinesitesindearşivlendi.,US State Department, Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor.

- ^Hungary's Constitution of 201123 Nisan 2018 tarihindeWayback Machinesitesindearşivlendi.. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ^"Concordat Watch – Portugal | Concordat (2004): text".concordatwatch.eu.11 Kasım 2020 tarihindekaynağındanarşivlendi.

- ^Wyeth, Grant (16 Haziran 2017)."Samoa Officially Becomes a Christian State".The Diplomat.16 Haziran 2017 tarihinde kaynağındanarşivlendi.Erişim tarihi: 8 Kasım 2020.

- ^Feagaimaali’i-Luamanu, Joyetter (8 Haziran 2017)."Constitutional Amendment Passes; Samoa Officially Becomes 'Christian State'".Pacific Islands Report. 11 Kasım 2020 tarihinde kaynağındanarşivlendi.Erişim tarihi: 8 Kasım 2020.

- ^Constitution of Zambia26 Şubat 2020 tarihindeWayback Machinesitesindearşivlendi.. Retrieved 19 October 2016.

- ^"Arşivlenmiş kopya".16 Temmuz 2021 tarihinde kaynağındanarşivlendi.Erişim tarihi:19 Mart2022.

- ^"Nepal Adopts New Constitution, Becomes a Secular State: 5 Facts".NDTV.20 Eylül 2015. 12 Kasım 2020 tarihinde kaynağındanarşivlendi.Erişim tarihi: 18 Aralık 2020.

- ^"The Constitution of Nepal"(PDF).wipo.int.20 Eylül 2015. 15 Şubat 2017 tarihindekaynağından(PDF)arşivlendi.

- ^"The Constitution of Afghanistan"(PDF).Afghanistan. 1987. 3 Temmuz 2009 tarihindekaynağından(PDF)arşivlendi.Erişim tarihi:30 Temmuz2009.

- ^"Avant Projet de Revision de la Constitution"(PDF).constitutionnet.org(Fransızca). 28 Aralık 2015. 17 Nisan 2017 tarihindekaynağından(PDF)arşivlendi.

- ^"The Constitution of the People's Republic of Bangladesh | 2A. The state religion".bdlaws.minlaw.gov.bd.10 Kasım 2019 tarihindekaynağındanarşivlendi.

- ^"Bangladesh's Constitution of 1972, Reinstated in 1986, with Amendments through 2014"(PDF).constituteproject.org.29 Ekim 2016 tarihindekaynağından(PDF)arşivlendi.Erişim tarihi:29 Ekim2017.

- ^"Bahrain's Constitution of 2002 with Amendments through 2012"(PDF).constituteproject.org.30 Ekim 2017 tarihindekaynağından(PDF)arşivlendi.Erişim tarihi:29 Ekim2017.

- ^"Brunei Darussalam's Constitution of 1959 with Amendments through 2006"(PDF).constituteproject.org.6 Haziran 2017. 11 Ağustos 2017 tarihindekaynağından(PDF)arşivlendi.

- ^"Comoros's Constitution of 2001 with Amendments through 2009"(PDF).constituteproject.org.6 Haziran 2017. 11 Ağustos 2017 tarihindekaynağından(PDF)arşivlendi.

- ^"Djibouti's Constitution of 1992 with Amendments through 2010"(PDF).constituteproject.org.6 Haziran 2017. 25 Haziran 2016 tarihindekaynağından(PDF)arşivlendi.

- ^"Unofficial translation of the 2014 constitution"(PDF).18 Temmuz 2015 tarihinde kaynağındanarşivlendi(PDF).Erişim tarihi: 8 Kasım 2020.

- ^"Iran (Islamic Republic of)'s Constitution of 1979 with Amendments through 1989"(PDF).constituteproject.org.20 Eylül 2016 tarihindekaynağından(PDF)arşivlendi.Erişim tarihi:29 Ekim2017.

- ^"Iraqi Constitution"(PDF).28 Kasım 2016 tarihindekaynağından(PDF)arşivlendi.

- ^"The Constitution of The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan".1 Ocak 1952. 26 Nisan 2013 tarihindekaynağındanarşivlendi.Erişim tarihi:29 Ekim2017.

- ^"Kuwait's Constitution of 1962, Reinstated in 1992"(PDF).constituteproject.org.11 Ağustos 2016 tarihindekaynağından(PDF)arşivlendi.Erişim tarihi:29 Ekim2017.

- ^"Draft Constitutional Charter For the Transitional Stage"(PDF).25 Nisan 2012 tarihindekaynağından(PDF)arşivlendi.Erişim tarihi:29 Ekim2017.

- ^"Maldives's Constitution of 2008"(PDF).constituteproject.org.30 Aralık 2016 tarihindekaynağından(PDF)arşivlendi.Erişim tarihi:29 Ekim2017.

- ^"Federal Constitution Incorporating all amendments up to P.U.(A) 164/2009"(PDF).Laws of Malaysia. 2 Şubat 2016 tarihindekaynağından(PDF)arşivlendi.Erişim tarihi:29 Ekim2017.

- ^"Mauritania's Constitution of 1991 with Amendments through 2012"(PDF).constituteproject.org.24 Ekim 2014 tarihindekaynağından(PDF)arşivlendi.Erişim tarihi:29 Ekim2017.

- ^"Morocco Draft Text of the Constitution Adopted at the Referendum of 1 July 2011"(PDF).constitutionnet.org.Buffalo, New York: William S. Hein & Co., Inc. 2011. 30 Ekim 2017 tarihindekaynağından(PDF)arşivlendi.

- ^"Oman's Constitution of 1996 with Amendments through 2011"(PDF).constituteproject.org.29 Ekim 2016 tarihindekaynağından(PDF)arşivlendi.Erişim tarihi:29 Ekim2017.

- ^"Part I:" Introductory"".Pakistani.org. 30 Ağustos 2001 tarihindekaynağındanarşivlendi.Erişim tarihi:4 Haziran2013.

- ^Mideastweb website15 Temmuz 2017 tarihindeWayback Machinesitesindearşivlendi..

- ^"The Constitution".24 Ekim 2004 tarihindekaynağındanarşivlendi.Erişim tarihi:29 Ekim2017.

- ^"The Basic Law of Governance".23 Mart 2014 tarihindekaynağındanarşivlendi.Erişim tarihi:29 Ekim2017.

- ^"The Federal Republic of Somalia Provisional Constitution"(PDF).24 Ocak 2013 tarihindekaynağından(PDF)arşivlendi.Erişim tarihi:29 Ekim2017.

- ^"United Arab Emirates's Constitution of 1971 with Amendments through 2004"(PDF).constituteproject.org.25 Mayıs 2015 tarihindekaynağından(PDF)arşivlendi.Erişim tarihi:29 Ekim2017.

- ^"The Constitution of the Republic of Yemen As amended on 20 February 2001"(PDF).constitutionnet.org.22 Nisan 2017 tarihindekaynağından(PDF)arşivlendi.Erişim tarihi:29 Ekim2017.