Mythbusters: Digital Public Infrastructure & Digital Public Goods

This blog is the third in our series exploring digital public infrastructure. From DG’s more than 20 years of experience in creating, delivering, and adapting open source and open data solutions, we’ve learned several best practices on how to make technology accessible and sustainable while prioritizing engagement from open source communities—these practices can be applied to building and implementing digital public infrastructure. Check out the other blogs in this series.

Since India popularized the term during it’s G20 presidency, digital public infrastructure (DPI) is the latest buzzword in ICT4D that everyone from Deloitte to UNDP to Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation is talking about. But the concept itself is not new: the internet and GPS are some of the earliest examples of DPI, and DG has a long history of building and advising on technology to support government service delivery. Although the international community has just now reached consensus on what digital public infrastructure is, there are still a lot of myths and misperceptions around the term, and the open-source technology that often powers it. In this blog, we’ll debunk some common myths we hear about DPI with facts, highlight some successes and failures, and show you some of the open-source DPI tools we’re following.

MYTH #1: Governments shouldn’t get in the business of building technology; leave digital infrastructure to the private sector

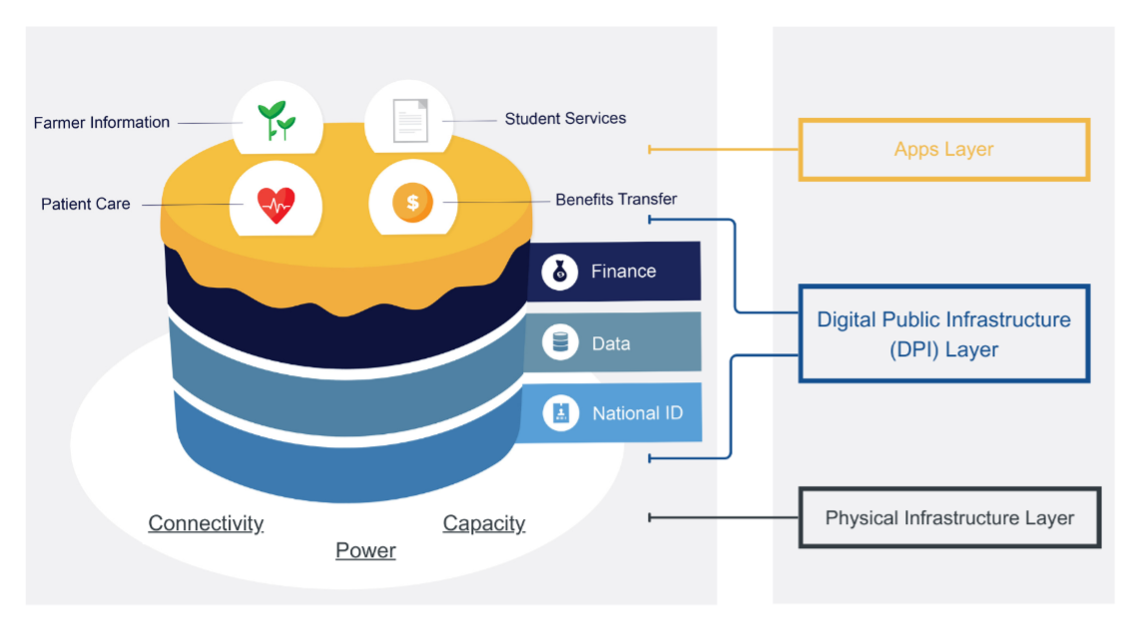

From distributing life-saving shelter, food, and medical attention after a disaster; to delivering government subsidies for seeds and fertilizer to smallholder farmers; to enrolling students for national examinations— these are the kinds of “public goods” not unlike roads that require a non-invisible hand to ensure citizens have equal and fair access. At a foundational “building block” level, this includes digital systems that give citizens:

- The ability to verify their identity

- The ability to share data accurately and securely

- The ability to make and receive payments

Source: Digital Impact Alliance.

Look no further than the US Department of Education’s disastrous handover of its loan repayment servicing to private-sector debt collectors like Mohela to understand the impact on student borrowers, let alone the Department of Education’s ability to collect payments. Or consider that the average American spends 13 hours and $240 on third-party tax software each year just to file taxes; and despite it being ostensibly free, standardized, and compulsory, 33% of Americans “completely” or “mostly” disagree that they trust the IRS to help them understand their tax obligations. In sum, the consequences of a free market approach to government digital transformation are felt most severely by citizens, which can foster and in some cases exacerbate mistrust in government technology systems.

MYTH 2: DPI, and the APIs and open-source software used to power it, are less secure and of lower quality because they’re free.

You’ve probably been using some very high-quality open-source technologies yourself and just didn’t know it. Some of the most widely-used examples of open-source software, both inside and outside of government, include the Linux operating system, Apache web server, and PostgreSQL database. Open-source tools specifically for DPI, also known as digital public goods, include DHIS2 for health; Moodle for education; openCRVS for civil, birth, and death registrations; the Open Contracting Platform for government procurement; and OpenStreetMap for GPS and mapping data.

The demand for these tools speaks to their quality: DHIS2 alone has been adopted in over 74 national health systems, and will be adapting its model for the education and agriculture sectors. And even if one of the existing open-source DPI tools doesn’t meet your exact quality standards, the beauty of open source is that you can customize or build on top of the foundational infrastructure to build any solution you want, much like we did for local health districts in Tanzania and the Ministry of Agriculture in Ethiopia.

Source: AfrICT (Africa ICT)

Piecemeal approaches to digital systems can make governments more vulnerable to potential risks. While open-source technology does have vulnerabilities (like any software), using open-source for DPI is arguably more secure than the alternative because it allows for cross-system interoperability, data validation, and cross-referencing. Public code review forums like GitLab (also open-source) and GitHub give users access to the latest security upgrades, bug fixing, and risk mitigation measures that would otherwise require extensive long-term support contracts or subscriptions. India regularly invites the best hackers in the country to intentionally break into the open APIs that power its digital public infrastructure, India Stack, and these hackathons have enhanced the security and protection of the technology.

While OSS can reduce licensing costs, there are still costs associated with implementation, customization, maintenance, and training. DPI projects also require substantial investments in infrastructure, development, and ongoing support. Taipei, for example, recently invested US$6.27 million to roll out a digital national ID program but had to pause in 2021 due to security concerns. Other experts in India estimate that the average cost of a digital identity program is about US$1 per person; meanwhile, costs for digital payment infrastructure can range from US$100 million in Thailand to only about US$2 million in Brazil.

However, the long-term economic impacts for society greatly outweigh the costs of deploying DPI. A McKinsey study recently estimated that Digital ID alone can boost economies by 3–13% of GDP, with an average of 6% growth in emerging economies. Governments that opt for open-source DPI can benefit from additional long-term cost savings by not having to renew licenses or software agreements, and adjusting or maintaining the technology in-house rather than contracting a third party.

MYTH 3: DPI increases inequalities and expands the digital divide

A recent Deloitte study confirmed that DPI can strengthen the government’s digital systems and facilitate equitable access to digital services. Take for example the successes of Ghana Post GPS, a digital addressing system that provides every location in Ghana with a unique digital address. Aside from ensuring your maps app will navigate you to the correct destination in Ghana (“Eye” Street in DC, I’m looking at you), this tool has improved citizens’ ability to access services, including emergency response, mail, and e-commerce; enabled more inclusive access to services for residents in remote and informal settlements; and facilitated business operations and logistics by providing precise location data.

DPI, when implemented with open data principles, can increase government transparency and accountability, enabling citizens to access and analyze public information. If implemented responsibly, DPI makes anonymized and real-time data available to citizens and civil society watchdogs, and the transparency provided by DPI can help improve civic engagement, increase trust in government, and credibility in a country’s decision-making. Further, by allowing anyone to contribute, open-source technologies foster innovation and collaboration across different sectors and geographies. Digital Public Goods communities have global reach and active online communities, which further support the reputation, neutrality, comparability, and trustworthiness of these systems.

In addition, open-source DPI solutions allow governments to avoid being locked into a single vendor’s ecosystem. This gives governments more flexibility and control over their IT systems, preventing dependence on high-cost, long-term contracts with the private sector. By using and developing their own digital infrastructure, governments can reduce dependency on foreign technology providers and protect their data sovereignty.

Looking ahead

Digital transformation offers countries the chance to establish robust public infrastructure and learn from others’ mistakes. However, challenges arise due to the lack of clear legal, regulatory, and policy frameworks for establishing interoperability across different ministries with distinct budgets, IT capabilities, capacities, and needs. Implementing digital public infrastructure also means answering questions related to governance, ownership, collaboration, resource-sharing, and sustainability. For instance, questions about who funds and maintains APIs between systems or how to integrate different platforms for various purposes highlight the complexities involved.

One solution could be establishing an independent intergovernmental agency, much like the UK’s Government Digital Services, to oversee and coordinate digital infrastructure. In emerging economies, development institutions and international banks can play a crucial role in financing public infrastructure, but purchasing the technology is not enough: DPI and DPG adoption must be supported by a robust and ethically governed regulatory environment to be sustainable. At DG, we look forward to continuing to work with our country government partners on their digital transformation journeys to dispel myths and misconceptions about DPI and DPGs, scale benefits to citizens by optimizing interoperability across sectors, and develop strong governance and accountability mechanisms that safeguard citizen and community rights.